Ensemble_Theater_Collaboration_Grant Program

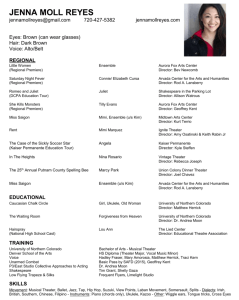

advertisement