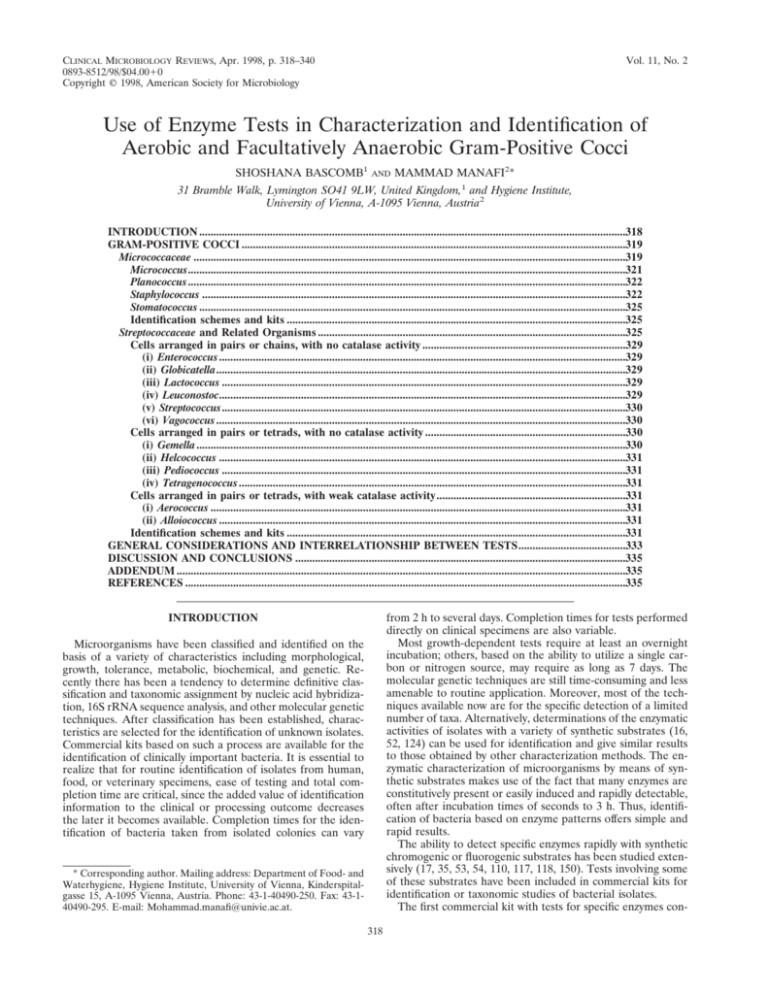

Use of Enzyme Tests in Characterization and Identification of

advertisement