2010 PRE-WEEK BAR EXAM NOTES ON LABOR LAW

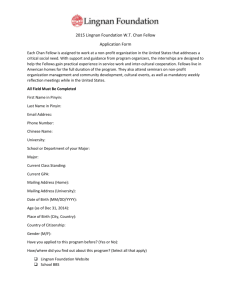

advertisement