BP and the Gulf Oil Spill

advertisement

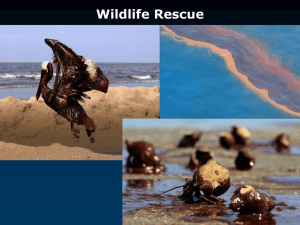

BP and the Gulf Oil Spill (A) The Event On the morning of April 20, 2010, a team of British Petroleum workers, 80 Transocean oil rig workers, Halliburton cementers, Schlumberger mud specialists, and various other specialized engineers were conducting preparations for the oil rig known as the Deepwater Horizon. Four days earlier, Halliburton engineers had started cementing the bottom of the oil well.1 Today, the cementing operations were complete. Mud specialists were scheduled to conduct a host of inspections to ensure the cementing operations were complete. However, because all parties involved were satisfied with the mud operations, the BP well team leader, John Guide, decided to postpone the inspection until drilling started. This would save the BP team a fee of $128,000 and significant amounts of time.2 Engineers routinely conducted tests to see if pressure rises or drops would occur inside the well and reveal cement integrity issues. An oil rig worker named Wyman Wheeler conducted the tests and was convinced that “something wasn’t right.”3 After Wheeler’s shift was up, other testers were not able to reach an acceptable pressures level from the main line. However, they reached zero pressure on a separate pipe, known as the “kill line” and concluded that all operations were safe. Workers then started pumping seawater into the main pipeline to remove mud from the pipeline at 9:20 pm.4 That night, a series of vibrations and hisses alerted the crew that there was a serious problem. Soon after, mud started spewing on the oil rig and a large explosion occurred and all power went out. The crew was alerted over a PA system that there was a fire on board. Chaos reigned. Multiple people were injured, lifeboats were dropped into the ocean, and individuals were jumping into the ocean. The mud propelled equipment 50 feet into the air, posing a major threat to the crew below. A supply vessel, the Bankston, maneuvered to rescue fallen workers. Steve Bertone told a subsea engineer, Christopher Pleasant, to use the emergency disconnect switch (EDS) to activate the blowout preventer. Jimmy Harrell, the Offshore Installation Manager, gave Mr. Pleasant the permission to activate the blowout preventer. Control panel lights indicated the blowout preventer was activated, but upon further inspection, the generator would not start. Coast Guard helicopters arrived at 11:22 pm and by 11:30 pm, final muster was taken with a result of 11 missing. By April 22, the rig was turned 180 degrees and far away from the well. Off Shore Drilling Challenges In September of 2009, BP discovered 4 to 6 billion gallons worth of oil reservoirs in the Gulf of Mexico. The reservoirs were 35,000 feet beneath the earth’s surface. At this depth, water pressure totals 10,000 pounds per square inch, well temperatures can exceed 350 degrees, and blowout preventers could only be installed by remote-operating vehicles. Drilling foundations were unstable due to pockets of methane in the sea floor.5 The purpose of offshore oil drilling is to find hydrocarbons that are trapped in the rock bed of the earth. The deeper the well, the greater the pressure of the rockbed above the hydrocarbons. Thus, drillers must ensure pressure is in equilibrium so that hydrocarbons do not shoot out of control to the surface. They do this by pumping mud into the wellbore to act as a counter balance. If the pressure is too great, the rock bed will break. If it’s too low, fluids and gas will enter the well and produce a “kick.”6 To ensure situations would not get out of control, blowout preventers could seal the well by squeezing the drill pipe shut. It also had five sets of rams to cut the drill pipe. It would be initiated by an automated system known as the “deadman” system. Cementing operations are necessary to bind the casing string to the hydrocarbon rockbed. The casing string is the apparatus used to draw the hydrocarbons from the rockbed. Cement is pumped through the casing string, and mud will force the cement out and around the string to the surrounding annular for a tight seal. This would ensure that the equipment is tightly sealed to the ocean floor so no pressure can escape.7 BP and Halliburton made a number of compromises in order to ensure that the oil well cementing process would produce maximum gains while reducing risk. The amount and rate of the cement that was pumped into the annulars was debatable. Engineers feared that the large amount of cement would cause a structural problem within the well.8 Thus, a less than conventional amount of cement was used to seal the annular. Key Entities British Petroleum British Petroleum was tottering on the brink of bankruptcy in the early 1990s. It was exiled by Nigeria and the Middle East. Sir John Browne was the force that turned the company around and ventured into the Gulf of Mexico for new oil well explorations.9 In August of 2002, BP would pump $15 billion into the Gulf of Mexico drilling. In March 2008, BP paid more than $34 million to the Minerals Management Service for an exclusive lease to drill in Mississippi Canyon Block 252, a nine-square-mile plot in the Gulf of Mexico.10 By 2010, it was the world’s fourth largest corporation and produced over 4 million barrels of oil day from 30 countries. Ten percent of BP’s output is drilled from the Gulf of Mexico.11 2 Transocean Transocean is the largest drilling contractor in the industry. A series of mergers throughout the 1990s and early 2000s would produce the company known as Transocean. In 2000, it acquired R&B Flacon, who had the ability to construct rigs like the Deepwater Horizon. Construction took place in Korea by Hyundai Heavy Industries.12 Transocean owned the underground submersible rig, known as the Deepwater Horizon. It also owned the original rig that drilled Macando, known as the Marianas. Transocean produced revenues of $11.6 billion in 2009. BP would lease the Deep water Horizon for over $1 million per day. Halliburton Halliburton engineers were responsible for cement operations on the rig.13 Cementing was necessary to close the bottom of the oil well from which the Deepwater Horizon was attempting to extract oil. Federal Government The federal government wrestles with two responsibilities that it must meet concurrently. First, the government operates the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which it created in 1970 to monitor activities that could pollute public lands, including offshore drilling. Normally, the Secretary of the Interior would approve offshore drilling and the approval processes would delay initial production for about six years. The Federal Government also desperately wanted to reduce U.S. energy dependence on foreign oil. During the Carter Administration, Iran imposed an oil embargo in 1979 that drove shortages in the United States, highlighting the need for energy independence.14 In order to compromise between these competing priorities, the Gulf of Mexico was given an exception to the NEPA Act because it was deemed that the oil and gas industry was already mature in the Gulf of Mexico.15 Minerals Management Services The chief federal agency responsible for overseeing drilling and operations is the Mineral Management Services, or MMS. MMS was charged with the mandate for environmental protection but also to drive the US to energy independence. In the Gulf, safety and environmental oversight was rendered ineffective because of these conflicting priorities. The agency lacked resources, technical training, and experience in the complicated world of offshore drilling.16 In other words, “The result was that the same agency became responsible for regulatory oversight of offshore drilling-and for collecting revenue from that drilling.”17 3 Furthermore, the MMS was, “…in one entity, authority of regulatory oversight with responsibility for collecting for the US Treasury the billions of dollars of revenues obtained from lease sales and royalty payments from producing wells.”18 A Brief History of British Petroleum In 1901, William Knox D'Arcy, a wealthy British miner, secured a concession from the Grand Vizier of Persia to search for petroleum throughout most of the Persian Empire. Persia was devoid of infrastructure and politically unstable at the time, making D’Arcy’s search physically challenging and more expensive than he anticipated. By 1905, D’Arcy was in critical need of additional capital in order to continue his search. With help from the British Admiralty, the Burmah Oil Company joined D'Arcy in a Concessionary Oil Syndicate in 1905 and supplied further funds in return for operational control. In May 1908 oil was discovered in the southwest of Persia at Masjid-i-Suleiman, the first oil discovery in the Middle East. The following April the Anglo-Persian Oil Company was formed, with the Burmah Oil Company holding most of the shares.19 Shortly after the discovery, the British Government bought up a majority of the AngloPersian Oil shares, an effort due in no small part to Winston Churchill. Churchill, who was then the chief of the British Navy, believed that the oil supplied from the Middle East would fuel the British Fleet through World War I and far into the future. The Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) ( as it was named in 1935) made handsome profits throughout the 1920s and 1930s as Western societies became more and more dependent on automobiles and petroleum burning manufacturing plants.20 In an effort to keep up with the rapidly growing demand from the West, The AIOC constructed the largest refinery in the world near the Iranian city of Abadan. This behemoth of a refinery employed over 200,000 Iranian workers in brutally harsh conditions. “Observers recounted the inequities between the Iranian workers housed in a rickety slum known as Kaghazabad, or ‘Paper City,’ and the British officials who supervised from air-conditioned offices and lawn-fringed villas. Water fountains were marked ‘Not for Iranians.’" 21 The refinery became the biggest supplier of oil to the Allied Powers during World War II, despite shortages of food and outbreaks of diseases throughout the workers and the region. Conditions became especially grim during the winter season, as the director of the Iranian Petroleum Institute wrote in 1949, "In winter the earth flooded and became a flat, perspiring lake. The mud in town was knee-deep and canoes ran alongside the roadways for transport. When the rains subsided, clouds of nipping, small-winged flies rose from the stagnant waters to fill the nostrils, collecting in black mounds along the rims of cooking pots and jamming the fans at the refinery with an unctuous glue."22 Horrific working conditions, unequal distribution of revenues, and small dividends began to fuel Iranian discontent with the AIOC. Additionally, the Iranian government became increasingly upset when the AIOC signed 50/50 revenue sharing agreements with other oil producing companies such as Venezuela and Saudi Arabia in 1948 and 1950, respectively. 4 Discontent reached a tipping point in 1951 when the democratically elected Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammed Mossadegh, formally nationalized Iran’s oil industry, effectively pushing AIOC out of the country. A few years of failed negotiations followed, and finally in 1953 the CIA and British Intelligence staged a coup in a joint effort, which was successful in the overthrow of Mossadegh. With Mossadegh removed, the newly installed Shah of Iran allowed the return of AIOC, which was renamed as the British Petroleum (BP) Company. However, BP’s terms of returning to the country were less favorable than before, as BP held a 40 percent interest in a newly created consortium of Western oil companies, formed to undertake oil exploration, production, and refining in Iran.23 Tensions between BP and Iran never cooled as generations of Iranians believed that the company’s intention was always to take advantage of cheap Iranian labor and exploit the country’s natural resources. These tensions played a large part in the growing anti-Western attitudes that developed throughout Iran and eventually helped pave way to the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Amidst growing anti-Western sentiment throughout the entire Middle Eastern region, BP began to look in different regions to expand its production, including the British North Sea and the Alaskan wilderness. In 1977, BP began pumping oil near Prudhoe Bay in northern Alaska through a 1,200 km-long pipeline that ran all the way to refineries in the southern part of the state. According to Tharoor Ishaan of Time magazine, “The project became one of the largest infrastructure projects ever attempted in North America and BP prided itself on the environmental sensitivity of its planning, which included raised platforms in certain stretches so as to not impede the natural migrations of caribou.” 24 Despite having great success beyond the Middle East, BP’s public image has been damaged by egregious safety violations, a misleading green marketing campaign, and most recently, the Deepwater Horizon offshore drilling rig explosion. BP and the Green Marketing Campaign BP began a massive $200M marketing campaign in 2000 to re-brand itself as “Beyond Petroleum.” BP’s shield logo, which had been in use for over 70 years, was redesigned into the BP “Helios,” a graphic that was intended to promote warm, green and clean energy sentiments about the company and its environmental-friendly attitude. BP’s CEO at the time, Lord John Browne, speaking at Stanford University in 2002, stated, “I believe the American people expect a company like BP . . . to offer answers and not excuses.” Additionally, Lord Browne proclaimed that, ''Climate change is an issue which raises fundamental questions about the relationship between companies and society as a whole, and between one generation and the next.'' He even said, ''Companies composed of highly skilled and trained people can't live in denial of mounting evidence gathered by hundreds of the most reputable scientists in the world.'' 25 With an advertising campaign focused on BP’s apparent efforts to invest in solar, wind, natural gas, and hydrogen sources of energy, BP seemed heavily invested in a eco-friendly culture and moving away from fossil-fuels. Behind the popular tag line “It’s a start,” BP successfully branded itself 5 as a new leader in alternative-energy research and production. BP’s Recent Safety Record BP’s recent string of mishaps, excluding the Gulf of Mexico disaster, seems to strongly contradict its environmental and safety friendly marketing effort. In 2005, a major explosion occurred at the BP Texas City refinery, in which 15 workers died and 170 were seriously injured. The ensuing investigations by the federal government strongly suggested that BP leadership was heavily focused on reducing maintenance and capitol costs at the expense of a proper safety environment. 26 The U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board organized an independent investigation, which was headed by former Secretary of State James Baker. The findings of the commission suggested that BP promoted a culture in which “occupational safety” and “process safety” could not be differentiated. Since the accident, there have been four subsequent safety violations in which workers have been injured at the same Texas City refinery, further suggesting that BP’s culture has not changed. In August of 2006, an estimated 5,000 barrels of crude oil began leaking from one of BP’s pipelines in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. Investigators determined that corrosion in a number of pipelines caused the leak. The public began to doubt that BP’s self-proclaimed environmentally friendly culture was sufficient enough to prevent future disasters. Finally, in a three-year time span prior to the Gulf of Mexico disaster, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration stated that BP racked up 760 “willful and egregious” safety violations, which constituted 97% of all industry safety violations during the period. Tony Hayward’s Ascent Tony Hayward received a PhD from the University of Edinburgh and began his career with BP in 1982.27 He excelled in his initial assignments and was given positions of greater responsibility throughout Europe and Asia in the first decade of his career. While attending a leadership conference in the United States in the early nineties, Hayward caught the eye of (then) BP CEO Lord Browne. After serving as an executive assistant to Browne for a couple of years, Hayward began to rise quickly through the ranks.28 He served as President of BP’s operations in Venezuela, as a director of BP exploration, a group Vice President and eventually as group treasurer, where he was responsible for a variety of key financial decisions that affected the entire company. Hayward replaced Lord Browne as CEO in May of 2007 after the Texas City Refinery explosion killed 15 people and wounded nearly 200 others. Prior to assuming the role as CEO, Hayward made it clear that he intended to integrate all levels of leadership in the decision making process. He believed, as he said in 2006, that “the top of the organization doesn’t listen hard enough to what the bottom of the organization is saying.”29 Taking charge of the company, Hayward vowed to intensify BP’s safety efforts, improve its 6 financial performance and adhere to core BP values.30 With such considerable experience throughout the company, it seemed as though Hayward was poised to follow through with his ambitious vision. Initial Communications Word got back to BP headquarters soon after the fatal explosion in the gulf killed 11 rig workers. After a tumultuous evening, Tony Hayward released a brief statement on BP’s website. In his statement he offered condolences to the families of the deceased and offered “support” to Transocean as it tried to make sense of the disaster.31 The statement conveyed BP’s genuine sincerity, but it also indicated that BP initially intended to play a supporting role in the recovery and clean-up effort. BP released its quarterly earnings report on April 27 and briefly mentioned the spill after a thorough discussion about robust earnings.32 On April 30, in a surprising change of tone, Hayward was quoted as saying that BP assumes “full responsibility for the spill.”33 Then, on May 2, Tony Hayward appears on the Today show and remarks, “It’s not our accident.”34 He then went on to say that although BP was not responsible for the incident, it would play a direct role in containing the oil spill. The first few days following the incident were certainly marred by confusion and contradiction on BP’s part. In the same two week period following the explosion, the federal government took a much more active role in finding fault and placing blame. In a special televised address on May 2, President Obama said “BP is responsible for this; BP will be paying the bill”.35 Two days earlier, President Obama appointed Admiral Thad Allen as National Incident Commander and gave him the authority to engage the public regarding current recovery efforts. Admiral Allen, highly regarded as an expert in disaster recovery, carried the full weight of the federal government when he spoke about the deepwater crisis. BP would often have to work closely with Admiral Allen or even under his guidance during certain parts of the recovery. BP’s Communications Strategy In addition to daily press conferences and remarks from senior leadership, BP used three key communications methods to engage local, national and global audiences. Social Media Prior to April 20, 2010, BP posted very few items and updates to its Twitter and Facebook accounts. In the week following the explosion, BP was silent on the social media scene. On April 27 at 8:26 pm, BP posted a message on its Twitter account, simply saying “BP PLEDGES FULL SUPPORT FOR DEEPWATER HORIZON PROBES.”36 After the initial post on Twitter, BP gave daily Twitter updates to interested followers. BP used Twitter to list important contact 7 information for each of its emergency response teams as well as to provide key updates on the search, rescue and recovery processes. BP used Facebook in a similar way. On May 2, BP America entered its first Facebook post, announcing that BP officials had established a hotline for those who would like to support with the cleanup and recovery efforts in the Gulf.37 BP’s Facebook page provided those who “liked” BP’s page with a detailed account of how much oil had been recovered that day and since the beginning of the spill. It also provided a variety of information regarding the compensation claims process, key Coast Guard updates and commerce in the Gulf area. BP officials would update Facebook followers several times a day (even on weekends and holidays) in order to make their efforts and intentions as transparent as possible. On May 5, BP began releasing official Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill updates on its website.38 Each update was linked to the Twitter and Facebook pages so that all users could funnel towards the official www.bp.com website to receive their information. The updates were robust and offered a detailed account of the day’s recovery efforts as well as a wealth of pictures, maps, graphics, diagrams, comments and assessments. All of this information would eventually lead to the creation of the “Gulf of Mexico Response” tab on the BP website. Anyone who wanted an update on the Gulf spill could easily and quickly get one from the BP website or through its social media outlets. Paid Media – “We Will Make This Right” BP invested in a massive print and television campaign in order to make its case as a responsible company that was willing to do the right thing at all costs and against all odds. The campaign began on June 3 with a television advertisement featuring Tony Hayward. In the advertisement, which aired in markets all over the United States, Hayward outlines BP’s immense recovery effort and pledges to stay in the Gulf as long as it takes to fix the problem.39 In addition to the national television campaign, BP also ran print advertisements in high visibility newspapers, including The New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post.40 This comprehensive advertisement strategy, designed to appeal to a national audience, carried with it a $50,000,000 price tag.41 According to a spokesman with BP, Tony Hayward justified the cost of the campaign by alluding to his obligation to keep the public informed about ongoing recovery efforts. Not everyone was pleased with the information Hayward communicated, at least not at a cost of fifty million dollars. President Obama, upon hearing an estimated cost of the campaign, said “What I don’t wanna hear is when they’re…spending that kind of money on TV advertising and they’re nickel and diming fishermen.”42 Mr. Obama was referring to the way that BP had been handling compensation claims for fishermen who were out of work as a result of the spill. He felt that the money may have been better spent supporting the people directly affected by the disaster, as opposed to financing a campaign to appeal to seemingly unaffected people. Spillcam 8 Congressman Ed Markey, the representative from Massachusetts’s 7th District, began criticizing BP for not giving the public access to its 24-hour camera feed of the oil spill. He believed that the public should have full disclosure to each camera angle in order to get a better idea of just how severe the spill really was.43 On May 18, BP made such footage available via its website. “Spillcam,” as the live feed eventually became known, drew immense fascination across the country. In the days following Spillcam’s release, more than 300,000 people visited BP’s website to view the feed. “BP oil spill live feed” and “top kill video” were both among the most popular Google searches after Spillcam’s release.44 BP disclosed the footage in an effort to prove its willingness to disclose vital information to the public and to highlight its cooperation with federal agencies. While Spillcam certainly represented transparency, it also gave the public a clear picture of the staggering oil flow that plagued the Gulf. Missteps Along the Way Downplaying the Effects A week after the Deepwater Horizon disaster, BP released noticeably upbeat quarterly earnings. In the notes section following the impressive earnings report, the Gulf oil spill was casually mentioned in a mere three sentences.45 The oil spill acknowledgment was sandwiched in between detailed descriptions of lucrative acquisitions and operating results. On the same day that BP went public with Spillcam, Tony Hayward did an interview with SkyNews. In the interview, he contends that the overall effects of the spill will be “very, very modest”46 and that the spill would be relatively small compared to the entire ocean.47 In early June, (months before the leak is sealed) Doug Suttles, BP’s Chief Operating Officer, remarked that the oil flow “will be down to a relative trickle” within a few days.48 A week later, oil was still flowing from the leak at a rate of 10,000 to 35,000 barrels per day. Suttles then went on to say “I would eat fish from these waters.” 49 He made the comment about a month before the well was sealed and while many fishermen were still out of business. The comment, though likely true, continued to aggravate people whose lives had been greatly disrupted by the disaster. Self-Inflicted Wounds BP’s extensive communications and advertisement effort would likely have been much more successful had it not been for a few avoidable mistakes. Tony Hayward, in an attempt to apologize to Gulf residents, said “There’s no one who wants this thing to be over more than me. I’d like my life back.” 50 He made the statement just three days before releasing the “We will make this right” advertisement. Many Gulf residents felt the comment was unbelievably insensitive, especially considering the fact that 11 men actually lost their lives in the incident. Two weeks before that statement, Tony Hayward was spotted at an exclusive yacht race off the coast of England, apparently on vacation with his son. The jet-setting lifestyle complete with luxurious yacht races was countered by the hardships and struggles Gulf residents were enduring every day. Many people affected by the spill were appalled by Hayward’s seemingly flippant and arrogant behavior. Hayward was not the only one to make a serious gaffe after the spill. Carl 9 Henric Svanberg, BP’s Chairman of the Board, told President Obama that BP cares about “America’s small people.”51 The comment was not received well by Gulf residents, who detected a hint of superiority and arrogance in the comment. On July 20, in the midst of another attempt to plug the oil flow, BP digitally altered a photo of employees viewing data screens in a command and control center. The photo was prominently displayed on the company website and was intended to show how closely BP was monitoring the situation. An online blogger noticed that the image had been “photoshopped” to make it appear as though the employees were monitoring more screens than they actually were.52 BP had to admit to the embarrassing mistake and apologize to the public once again. Moving Forward Bob Dudley replaced Tony Hayward on October 1 as BP’s CEO. After enduring the company’s most devastating accident and a number of public relations gaffes, Dudley has to rebuild BP’s image and regain credibility with customers and investors. In the aftermath of such a disaster, he must find a way to convince the public that BP is still a valuable energy company that will help solve global energy problems in the future. Discussion Questions 1. Do you think BP’s turbulent history contributed to its present day culture and general attitude towards safety and operational procedures? 2. How would you assess the effectiveness of BP’s Green campaign? 3. What should BP have communicated to the world immediately following the explosion? 4. Who should BP have used as the public relations “pointman” during the cap effort? 5. Will America ever forgive BP? 6. Will BP be able to repair its image and convey a new attitude of safety consciousness? 7. How does BP ensure a similar crisis does not occur in the future? 8. What is Bob Dudley’s greatest challenge as he tries to improve BP’s public image and grow profitability? References 10 1 Graham, Bob, et al., Deepwater: The Gulf Oil Disaster and the Future of Offshore Drilling, National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, January 2010: page 2. <http://www.oilspillcommission.gov/sites/default/files/documents/DEEPWATER_ReporttothePresident_ FINAL.pdf> 2 Ibid, page 4. 3 Ibid, page 6. 4 Ibid, page 7. 5 Ibid, pages 51-52. 6 Ibid, page 91. 7 Ibid, pages 94-99. 8 Ibid, pages 99-100. 9 Ibid, page 45. 10 Ibid, page 89. 11 Ibid, page 2. 12 Ibid, page 44. 13 Ibid, page 2. 14 Ibid, page 59. 15 Ibid, page 80. 16 Ibid, page 115. 17 Ibid, page 65. 18 Ibid, page 56. 19 FundingUniverse, The British Petroleum Company plc, 20 Tharoor, Ishaan. “A Brief History of BP.” Time Magazine. June 2, 2010. <http://www.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1993361,00.html> 21 Ibid. <http://www.fundinguniverse.com/companyhistories/The-British-Petroleum-Company-plc-Company-History.html> 11 22 Ibid. 23 FundingUniverse, The British petroleum Company plc, <http://www.fundinguniverse.com/companyhistories/The-British-Petroleum-Company-plc-Company-History.html> 24 Tharoor, Ishaan, “A Brief History of BP.” Time Magazine. June 2, 2010. <http://www.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1993361,00.html> 25 Frey, Darcy, “How Green is BP?” The New York Times, Dec 08, 2002. <http://www.nytimes.com/2002/12/08/magazine/how-green-is-bp.html> 26 Goodwyn, Wade, “Previous BP Accidents Blamed on Safety Lapses,” National Public Radio www.npr.org, May 6, 2010. <http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=126564739> , 27 Cronin, Jon, “Tony Hayward – BP’s New Boss,” BBC News, January 12th, 2009 <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/6257149.stm> 28 Tony Hayward biography, <www.BP.com>, Also from Bio.True Story, Tony Hayward Biography <http://www.biography.com/articles/Tony-Hayward-586098> 29 “Hayward Shares Candid Views on 2006,” The Telegraph, December 18th, 2006 <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/2952547/Hayward-shares-candid-views-on-2006.html> 30 Ibid. 31 “BP Offers Full Support to Transocean After Drilling Rig Fire,” April 21st, 2010 <http://www.bp.com/genericarticle.do?categoryId=2012968&contentId=7061458> 32 BP p.l.c. Group Results, First Quarter 2010, page 4 <http://www.bp.com/liveassets/bp_internet/globalbp/STAGING/global_assets/downloads/B/bp_first_qua rter_2010_results.pdf> 33 Bergin, Tom, “Exclusive: BP CEO says will pay oil spill claims,” Reuters, April 30th, 2010 <http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/04/30/us-bp-oilspill-idUSTRE63T2VR20100430> 34 The Today Show, Interview with Tony Hayward, May 2nd 2010. TPM Muckraker, May 4, 2010 <http://tpmmuckraker.talkingpointsmemo.com/2010/05/bp_chief_claims_oil_spill_wasnt_our_accident.p hp> 35 Obama, Barack, “Presidential Remarks on the Oil Spill,” The White House, May 2nd 2010, Louisiana, USA. <http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-oil-spill> 36 BP Twitter account, April 27th , 2010, <http://twitter.com/BP_America/status/12984677193> 37 BP America Facebook page, May 2nd , 2010 <http://www.facebook.com/topic.php?uid=121928837818541&topic=133> 12 38 “Update on Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill Response,” <www.bp.com>, May 5th, 2010 39 “A Message from Tony Hayward,” You Tube, June 3, 2010 <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KKcrDaiGE2s> 40 Smith, Aaron. “BP’s Television Ad Blitz,” CNN Money, June 4th, 2010 <http://money.cnn.com/2010/06/03/news/companies/bp_hayward_ad/index.htm> 41 Ibid. 42 Reid, Chip, “Obama Lashes Out at BP’s PR Spin,” CBS News, June 4, 2010 <http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2010/06/04/eveningnews/main6549303.shtml> 43 Wheaton, Sarah, “Gulf Reality Show Draws a Big Web Audience,” The New York Times, May 26 2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/27/us/27spillcam.html> 44 Ibid. 45 BP p.l.c. Group Results, First Quarter 2010, Page 4 <http://www.bp.com/liveassets/bp_internet/globalbp/STAGING/global_assets/downloads/B/bp_first_qua rter_2010_results.pdf> 46 Milam, Greg, “BP Chief: Oil Spill Impact ‘Very Modest,’ SkyNews, May 18, 2010 <http://news.sky.com/skynews/Home/World-News/BP-Oil-Spill-In-Gulf-Of-Mexico-Will-Have-Very-Mo dest-Environmental-Impact-Says-Firms-CEO/Article/201005315633987> 47 Webb, Tim, “BP boss admits job on the line over Gulf oil spill,” May 14, 2010, The Guardian <http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2010/may/13/bp-boss-admits-mistakes-gulf-oil-spill> 48 The Today Show, Interview with Doug Suttles, June 9, 201, Video available on The Huffington Post <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/06/09/underwater-plumes-doug-su_n_605613.html> 49 Weber, Harry R., “BP executive says he would eat fish from Gulf of Mexico,” Associated Press, Aug. 1, 2010. <http://blog.al.com/live/2010/08/bp_executive_says_he_would_eat.html> 50 The Today Show, May 30, 2010 available from You Tube, “BP CEO Tony Hayward: ‘I’d Like My Life Back,” <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MTdKa9eWNFw&feature=player_embedded> 51 Bazinet, Kenneth, R., “BP boss Svanberg says ‘we care about the small people’ after oil spill faceoff with President Obama,” NYDailyNews.com, June 17, 2010. <http://articles.nydailynews.com/2010-06-17/news/27067379_1_small-people-oil-spill-toby-odone> 52 Mufson, Steven, “Altered BP photo comes into question,” The Washington Post, July 20, 2010 <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/07/19/AR2010071905256.html> 13