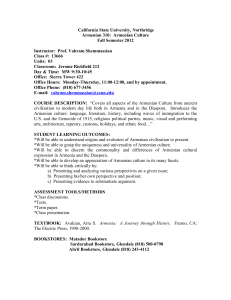

Noah's Dove Returns. Armenia, Turkey and the Debate on

advertisement