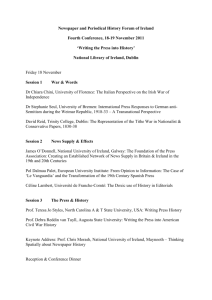

Shan Van Vocht: Political Communication & Irish Nationalism

advertisement