How Leaders Foster Self-Managing Team Effectiveness: Design

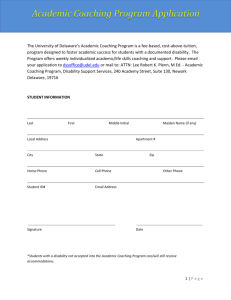

advertisement