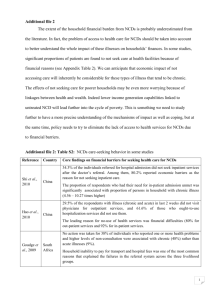

The Challenge of Non-Communicable Diseases and

advertisement