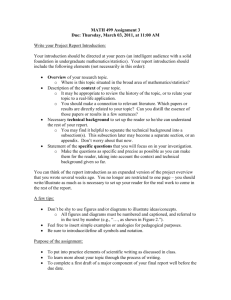

A Teacher's Guide to Technical Writing

advertisement