Postneonatal mental and motor development of infants exposed in

advertisement

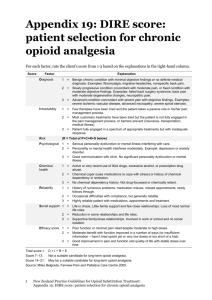

IMHJ (Wiley) LEFT INTERACTIVE top of AH A R T I C L E POSTNEONATAL MENTAL AND MOTOR DEVELOPMENT OF INFANTS EXPOSED IN UTERO TO OPIOID DRUGS SYDNEY L. HANS Department of Psychiatry, The University of Chicago RITA J. JEREMY Department of Pediatrics, The University of California, San Francisco ABSTRACT: We compared the mental and motor development of 33 infants from innercity, African American families whose mothers used opioid drugs during pregnancy with that of 45 infants from demographically comparable families where the mothers were not users of opioids. We found that during the first 2 years of life, the children exposed to opioid drugs showed poorer functioning on Bayley Scales mental and psychomotor development indices as well as on Infant Behavior Record ratings of mental and motor functioning. Although both groups of children performed in the normal range during infancy, both groups showed sharp declines in their developmental scores during the second year of life relative to norms. The poorer performance of the opioid-exposed group in mental development was related to social-environmental risk factors; in psychomotor development, to reduced birth weight. RESUMEN: En este estudio se comparó el desarrollo mental y motor de 33 infantes que provenı́an de familias afro-norteamericanas de barrios pobres del centro de la ciudad y cuyas madres habı́an usado drogas similares al opio durante el embarazo, con 45 infantes de familias demográficamente comparables donde las madres no usaron tales drogas. Encontramos que durante los dos primeros años de vida, los niños expuestos a dichas drogas mostraron un funcionamiento más débil en los ı́ndices de desarrollo mental y sicomotor de las Escalas Bailey, ası́ como en las clasificaciones de funcionamiento mental y motor de la Trayectoria de Comportamiento Infantil (Infant Behavior Record). Aunque ambos grupos de niños actuaron dentro de lo normal durante la infancia, los dos mostraron una declinación fuerte en cuanto a los puntajes de desarrollo durante el segundo año de vida, en lo relativo a las normas. La más débil actuación del grupo de niños expuestos a estas drogas en lo que respecta al desarrollo mental fue relacionada con factores de riesgo socio-ambientales; y en cuanto el desarrollo sicomotor, al bajo peso al momento del nacimiento. Data for this article were collected with the support of grant PHS 5 R01 8 DA-01884 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. While preparing this article, the first author was supported by grant R01 DA05396-01A1 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. We thank Wendy Rabinowitz, Susan Lutgendorf, Karen Freel, and Ora Aviezer for their assistance in collecting the data; and Joseph Marcus, Carrie Patterson, Victor Bernstein, and Linda Henson for their support throughout the conduct of this study and preparation of this article. Direct correspondence to: Sydney L. Hans, Department of Psychiatry, MC3077, 5841 S. Maryland Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637; phone: (773) 702-6313; fax: (773) 702-5352. INFANT MENTAL HEALTH JOURNAL, Vol. 22(3), 300– 315 (2001) 䊚 2001 Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health 300 short standard base of drop IMHJ (Wiley) RIGHT INTERACTIVE Infants Exposed to Opioid Drugs ● 301 RÉSUMÉ: Nous avons comparé le développement mental et moteur de 33 enfants en très bas âge issus de top of rh base of rh cap height base of text quartiers très défavorisés, de familles noires américaines dont les mères utilisèrent des drogues dérivées de l’opium durant leur grossesse avec 45 enfants en très bas âge issus de familles à la démographie comparable, et dont les mères n’utilisèrent pas de drogues dérivées de l’opium durant leur grossesse. Nous avons trouvé que durant les deux premières années de la vie, les enfants exposés à des drogues dérivées de l’opium réussissaient bien moins bien aux indices de développement mental et psychomoteur de l’Echelle de Bayley et réussissaient également bien moins bien pour ce qui concerne les scores de fonctionnement mental et moteur du Niveau de Comportement du Nourrisson (Infant Behavior Record en anglais). Bien que les deux groupes d’enfants se comportèrent normalement durant la toute petite enfance, les deux groupes firent preuve de très fortes baisses dans leur scores comportemental durant leur deuxième année, comparé aux normes. La plus mauvaise performance (en développement mental) du groupe exposés aux drogues dérivées de l’opium était liée à des facteurs de risques du milieu social, et, pour ce qui concerne le développement psychomoteur, à un poids à la naissance très bas. ZUSAMMENFASSUNG: Wir verglichen die geistige und motorische Entwicklung von 33 Kleinkindern aus innenstädtischen, afroamerikanischen Familien in denen die Mütter Opiate während der Schwangerschaft eingenommen hatten, mit demographisch vergleichbaren Familien von 45 Kindern, deren Mütter keine Opiate einnahmen. Wir fanden, dass in den ersten zwei Lebensjahren die Kinder, die Opiaten ausgesetzt waren, schlechtere Werte der geistigen und psychomotorischen Entwicklungsparametern auf der Bayley Skala hatten, sowohl als auch in der geistigen und motorischen Funktionen, gemessen mit dem KleinkindVerhaltens-Bogen. Obwohl beide Gruppen von Babys im ersten Lebensjahr dieselbe Leistung zeigten, hatten beide Gruppen starke Abfälle in ihren Entwicklungsparametern im zweiten Lebensjahr im Vergleich zu den Normen. Die schlechteren Ergebnisse der opiat-ausgestzten Gruppe im Bezug auf die geistige Entwicklung kann in Beziehung gesetzt werden zu sozial— umweltbedingten Risikofaktoren; bei der psychomotorischen Entwicklung zu dem geringeren Geburtsgewicht. * * * Abuse of alcohol and drugs during pregnancy is an issue of great public concern in the United States (e.g., Kantrowitz, 1990; Toufexis, 1991). Yet, most research on this topic has focused on the use of alcohol and cocaine during pregnancy. The present article addresses the impact of maternal opioid abuse on early child development. Abuse of opioid drugs — the drugs that pharmacologically are related to morphine — is a longstanding social problem in the United States (cf. Zagon & McLaughlin, 1984). While opioid addiction decreased during the recent cocaine epidemic, there has been a resurgence of opioid use as part of the historically cyclical nature of drug abuse in this country (Frank & Galea, 1996; Musto, 1987). For most of the 20th century, American opioid abuse primarily involved illicit heroin, intravenously injected (Kinlock, Hanlon & Nurco, 1998). Recently, as purer, inhalable forms of heroin have been introduced, a new generation of heroin users has emerged (Martin, Hecker & Clark, 1991). A large proportion of heroin addicts are from lower short standard IMHJ (Wiley) 302 ● LEFT INTERACTIVE S.L. Hans and R.J. Jeremy socio-economic strata, and their drug abuse further depletes their limited physical, medical, and social-emotional resources. As users of illicit drugs, heroin users must structure their lifestyles around drug procurement, and usually resort to illegal activities to support their habits. Since the mid-1970s, chronic heroin addicts who seek treatment in the United States have often been admitted to government-funded methadone maintenance programs where they receive free daily oral doses of methadone, a synthetic opioid (cf. Hutchings, 1985; Parrino, 1993; Payte, 1997). Methadone has effects similar to, but longer lasting than those of heroin, thus making methadone better suited for treatment programs in which medication is administered on a once daily basis. Methadone is generally dispensed in a clinic setting that may also provide a variety of social services and medical supervision to its clients. In general, people maintained on methadone lead more stable lives than they did as heroin addicts, and are assured of better pharmacological control of their addiction. Opioid drugs easily cross the placenta (Blinick, Inturrisi, Jerez, & Wallach, 1975) and have effects on the fetus that can be clearly observed during the neonatal period. Numerous studies of opioid exposure on human fetal growth have found that maternal use of opioid drugs — even medically supervised use of methadone — is related to lower weight at birth and to reduced head circumference (reviewed by Hans, 1992). Although maternal opioid use has generally been confounded with exposure to other drugs (including tobacco and alcohol), poor quality prenatal care, poor maternal nutrition, and maternal infection, the number of replications of the basic findings and the similar lowered birth weight in opioid-exposed rat pups (cf. Zagon & McLaughlin, 1984) suggest that the opioids themselves are at least one contributor to lowered birth weight in exposed children. Currently, the reduced birth weight and head circumference are believed to be the result of intrauterine growth retardation rather than premature birth (Doberczak, Thorton, Berstein, & Kandall, 1987; Kandall, Albin, Gartner, Lee, Eidelman, & Lowinson, 1977). Within 1 to 3 days of birth, most infants born to opioid-addicted women show clear clinical signs of narcotics abstinence — or withdrawal (Desmond & Wilson, 1975; Kandall, 1998; Pierog, 1977; Zelson, Rubio, & Wasserman, 1971). These signs include a large number of symptoms of both nonspecific central and autonomic nervous system dysfunction. Among the more frequently observed medical signs of neonatal abstinence are: poor sleeping, hyperactive reflexes, convulsions, poor feeding, regurgitation, diarrhea, dehydration, yawning, sneezing, nasal stuffiness, sweating, skin mottling, fever, rapid respiration, and excoriation of skin. Carefully controlled observational studies of these children using the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (Brazelton, 1973) have also shown a clear pattern of abnormal neonatal behavior during the period of withdrawal (Chasnoff, Hatcher & Burns, 1982; Jeremy & Hans, 1985; Strauss, Lessen-Firestone, Starr & Ostrea, 1975). The replicated evidence from these studies (reviewed by Hans, 1992) leads to the conclusion that opioid-exposed neonates are much more easily aroused and aroused to higher levels than other newborns. This pattern of behavior is similar to the increased irritability reported by adults withdrawing from opioid drugs. In addition, opioid-exposed newborns show poorer motor control (tremulousness and jerkiness) and higher muscle tonus — both signs of increased CNS irritability and similar to motoric symptoms reported in adults experiencing narcotics withdrawal. Opioid-exposed neonates are also less likely to be in alert states during testing, although when alert, the quality of their responsiveness is normal. Some evidence suggests that neonates who were prenatally exposed to opioids orient and habituate relatively better to auditory than to visual stimuli, possibly because visual stimuli require more highly organized states of attentiveness to process effectively. The dramatic symptoms of neonatal abstinence diminish quickly over the first month of life until they are clinically nonsignificant (e.g., Jeremy & Hans, 1985). It remains an open question whether subtle behavioral problems linger past the neonatal period or emerge as top of rh base of rh cap height base of text short standard IMHJ (Wiley) RIGHT INTERACTIVE Infants Exposed to Opioid Drugs ● 303 development progresses. A small number of studies, all using relatively limited sample sizes with limited statistical power have presented different findings on this issue (reviewed in Hans, 1998). Some studies have concluded that there are no developmental deficits after the neonatal period due to maternal opioid use (Kaltenbach & Finnegan, 1987; Kaltenbach, Graziani, & Finnegan, 1979). Most others have reported small differences between exposed and unexposed children, particularly on aspects of behavior measured through rating scales or other qualitative techniques (Hans, 1989; Johnson, Diano & Rosen 1984; Rosen & Johnson, 1982; Strauss, Starr, Ostrea, Chavez, & Stryker, 1976; Wilson, 1989; Wilson, Desmond, & Wait, 1981). There have been no reports of serious developmental problems attributable to prenatal opioid exposure. Because most studies of opioid-exposed children, in fact, most studies of children of drugusing parents, have been conducted out of concern for the drug’s potential teratological or toxic effects, other mechanisms that might explain associations between maternal drug abuse and child development have generally not been given adequate attention in research on children exposed to opioids in utero (Aylward, 1982; Hans, 1992; Marcus & Hans, 1982). Other factors associated with maternal opioid use during pregnancy that could affect child development include: (a) use of alcohol or nonopioid drugs that could have teratological or toxic effects, (b) familial behavioral and learning disorders that could be transmitted genetically, (c) pregnancy and delivery complications, including reduced fetal growth, that may be related to maternal drug use, and (d) postnatal psychosocial factors, including the effects of poverty, stress, maternal psychopathology, maternal life style, disruptions in maternal care, and direct interaction with the primary caregiver. Yet, relatively little attention has been given in empirical studies of prenatal opioid exposure to whether differences between exposed and unexposed children can be attributed to the direct teratological effects of the drug or whether they might be explained by other factors. An exception is the work of Johnson, Glassman, Fiks, and Rosen (1987), who found evidence that drug effects on cognitive and neurological behavior in 3-year-old children were not direct but related to labor and delivery complications and disorganized family environments. The present article reports on a longitudinal study of the mental and motor development during the first 2 years of life of infants exposed prenatally to opioid drugs. The goals of the article are to discuss as to whether the behavior of infants born to drug-addicted women differs from that of demographically comparable unexposed children, but, more importantly, to explore the relation of drug exposure to mental and motor development in conjunction with other risk factors. In particular, we ask whether any drug effects might be attributable to other variables that are associated with maternal opioid use, specifically use of other potentially teratogenic substances, pregnancy and birth complications, and social-environmental factors. top of rh base of rh cap height base of text METHOD Subjects This article will report on the development during the first 2 years of life of 33 children who were exposed prenatally to opioid drugs and a comparison group of 45 infants whose mothers were not using any opioid drugs during pregnancy. Between the years of 1978 and 1982, 36 women who used opioid drugs throughout pregnancy were recruited during pregnancy at the prenatal clinics of Chicago Lying-In Hospital. Drug-using mothers were excluded from the sample who had chronic medical problems such as diabetes, obvious mental illness, or who were not between the ages of 18 and 35. All women short standard IMHJ (Wiley) 304 ● LEFT INTERACTIVE S.L. Hans and R.J. Jeremy at the time of recruitment were participating in methadone-maintenance programs for the treatment of intravenous heroin abuse. Most women had been involved in methadone-maintenance throughout pregnancy, some had sought treatment during pregnancy. Methadone dosages during pregnancy ranged from 3 to 40 mg per 24-hour period with a mean of less than 20 mg. These dosing levels are lower than reported in most other studies of prenatal opioid exposure. During the 4-year recruitment period, the women from the methadone group delivered 42 infants, including one pair of twins. Infants were excluded from this paper who had identifiable medical conditions impacting their test performance. Data from nine of these infants were not collected or are not presented in this article for the following reasons: infant death (n ⫽ 4, including one of the twins), infant who suffered a stroke and could not be administered Bayley Scales (n ⫽ 1), child with extremely poor Bayley scores who was later diagnosed as autistic (n ⫽ 1), infants with data missing from more than one of the five assessment ages (n ⫽ 3). A comparison group of 43 pregnant women who used no opioid drugs was recruited from the same prenatal clinics. In addition to the age and illness exclusion criteria used for the opioid group, women were excluded from the comparison group who had any reported history of opioid or cocaine use, who had a positive urine screen for opioid or cocaine use, or who consumed more than one drink a day of alcohol. The comparison-group mothers delivered 47 infants during the duration of the recruitment, including one pair of twins. Data from two of the comparison-group infants were not collected or are not presented in this paper for the following reasons: infant with cerebral palsy who scored extremely poorly on Bayley Scale items involving motoric responses (n ⫽ 1) and infants with data missing from more than one of the five assessment ages (n ⫽ 1). All women from opioid and comparison groups were African Americans residing in lowincome innercity neighborhoods. All women received regular prenatal care at a university medical center beginning no later than the second trimester. The drug-using women received transportation from their homes to prenatal appointments provided by their methadone clinics. As research participants, women received prenatal ultrasound screening and fetal monitoring during labor that were not provided as part of routine obstetric practice at the time of the study. All infants remained with their families after birth. The two groups were similar on age (methadone mean ⫽ 27.1 years, comparison mean ⫽ 25.8), socio-economic status (methadone 58% Hollingshead level 5; comparison 51% level 5), number of previous children (methadone mean 3.2, comparison mean 2.8), and intelligence (methadone mean ⫽ 89.9, SD ⫽ 12.0; comparison mean ⫽ 89.7, SD ⫽ 9.8). Sibling pairs were included in all statistical analyses. No families provided more than two children for the study. Although inclusion of sibling pairs violates rules of independent sampling, it should be noted that sibling pairs often had quite different mental and motor performance as well as quite different risk profiles because of differences in birth weight, prenatal exposure patterns, and patterns of parent – child interaction. The neonatal behavior of these infants was assessed at 3 days and 1 month, and has been described by Jeremy and Hans (1985). The postneonatal behavior of the infants was followed longitudinally at 4, 8, 12, 18, and 24 months of age, and will be reported in this article. top of rh base of rh cap height base of text Mental and Motor Outcome Variables At each of the follow-up ages, infants and their mothers were transported to a laboratory at the University of Chicago for assessment on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley, 1969). Carefully trained and supervised female examiners who were blind to any information about the mothers’ drug use or infants’ medical history administered the examination. At the end of each session, examiners were asked to guess whether the child was from the opioid or short standard IMHJ (Wiley) RIGHT INTERACTIVE Infants Exposed to Opioid Drugs ● 305 comparison group. It is noteworthy that the examiners’ guesses were not correlated with infants’ actual group membership at any age after the neonatal period. The Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley, 1969) consist of three parts: mental and motor sections that evaluate level of performance, and a behavior section that evaluates the quality of performance. The mental and motor sections are scored on age-normed scales called the Mental Development Index (MDI) and the Psychomotor Development Index (PDI), each with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 16. The third section, the Infant Behavior Record (IBR), rates qualitative aspects of the infant’s behavior on a series of nine- and fivepoint items completed by the examiner at the end of the testing session and based on the clinical impressions made throughout the session. Matheny (1980) has identified factors for consolidating the 27 IBR items; the item composition of these factors was slightly different at different ages. Following Matheny’s analyses, we identified three subsets of IBR items that we judged reflected aspects of neurobehavioral functioning, and that had validity across ages and made sums of those items. The sums were: Attention Sum (object orientation, #8, goal directedness, #11, and attention span, #12); Activity Level Sum (activity, #14, energy level, #25), and Motor Coordination Problems Sum (coordination of gross muscle movements, #26, coordination of fine muscles #27). It should be noted that the IBR gross and fine coordination items are scaled so that higher scores indicate greater problems. Three of the subjects followed longitudinally were not administered the Bayley Scales at the 24-month assessment only. So as not to drop these subjects from statistical analyses involving repeated measures, their MDI, PDI, and IBR sums were estimated by taking a median of their personal scores at the 18-month assessment and the average scores for the entire sample at 24 months. top of rh base of rh cap height base of text Measurement of Opioid Exposure After their recruitment, usually during the third trimester, mothers were interviewed about their drug-use history with a modified version of the University of Washington Pregnancy and Health Questionnaire (1974). Urine toxicology screens were conducted at the time the interview was administered and repeated later during pregnancy. Because mothers’ methadone doses were all relatively low, and because some mothers occasionally supplemented with illegal opioids whose use could not be reliably assessed, opioid exposure was coded for this study as a dichotomous grouping variable rather than as a continuous measure of dose level. Other Relevant Variables We examined three types of variables that could mediate an association with maternal opioid use: use of substances other than opioids, environmental factors, and birth weight. Use of substances other than opioids. While many of the opioid-group women occasionally used other opioid drugs (primarily heroin and pentazocine), the use of illicit nonopioid drugs was considerably lower at the time the families were recruited than it is today, and in particular, the expense of cocaine prevented its frequent use by low-income women. Women’s use of drugs and alcohol in the past and during the present pregnancy was determined through an intake interview and a modified version of the University of Washington Pregnancy and Health Questionnaire (1974). Urine toxicology screening was conducted twice during pregnancy to verify the self-reports. Based on the mothers’ self-reports, alcohol use was coded into three categories: abstinence, light to moderate (less than two drinks per day on average), and heavy short standard IMHJ (Wiley) 306 ● LEFT INTERACTIVE S.L. Hans and R.J. Jeremy drinking (greater than or equal to two drinks a day). Cigarette use was coded into three categories: abstinence, less than a pack a day, and at least a pack a day. Marijuana use was coded into four categories: abstinence, irregular use (once a week or less), regular light use (two to five joints per week), and regular heavy use (five joints or more per week). Cocaine use was coded into two categories: abstinence and use at least once during pregnancy. Reports were made separately for prepregnancy and each trimester of pregnancy and were highly intercorrelated across time epoch (e.g., between first and third trimesters, r ⫽ .92 for cigarettes, .83 for marijuana, and .69 for alcohol). Because reports were actually being made during the third trimester of pregnancy and biochemical verification was available for third trimester reports, only the third trimester variables were entered into the analyses described below. Exploratory analyses were conducted examining relations of child behavior to first trimester and prepregnancy substance use patterns and patterns of binge drinking, but are not reported because patterns of significant findings were not substantially different than those generated from the third trimester variables. top of rh base of rh cap height base of text Social-environmental risk factors. Because our own previous work and that of others has indicated that a measure of cumulative social-environmental risk is a more powerful predictor of child functioning than individual measures of such risk, we computed a social-environmental risk score. Following from the work of Sameroff and colleagues (Sameroff, Seifer, Barocas, Zax, & Greenspan, 1987), we did this by dichotomizing and tallying eight social-environmental risk variables: maternal education, maternal IQ, family socioeconomic status, maternal adaptive functioning, psychosocial stressors, and maternal behavior in interaction with the infants at 4, 12, and 24 months (see Bernstein & Hans, 1994, for further details of risk score calculation). A number of the variables that went into this risk score were assessed during prenatal interviews as follows: maternal education (measured in terms of years of school completed, less than 11 years counted as a risk), family socioeconomic status (measured on the Hollingshead TwoFactor Index of Social Position; Hollingshead & Redlich, 1958; Level 5 counted as a risk), maternal adaptive functioning (following psychiatric interviewing rated on DSM-III Axis 5, American Psychiatric Association, 1987, with poor or worse counted as a risk), maternal stressors (following psychiatric interviewing scaled on DSM-III Axis 4; more than moderate psychosocial stressors counted as a risk), and maternal intelligence (measured by the full-scale score from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; Wechsler, 1955; with IQ less than 85 counted as a risk). Maternal behavior in interaction with the infant was scored from videotapes at three ages. When the children were 4, 12, and 24 months old, they were videotaped in interaction with their caregivers in a laboratory setting in a variety of structured and unstructured situations that lasted between 15 and 40 minutes. The video sessions were rated on the Parent – Child Observations Guides for Program Planning (PCOGs) (Bernstein, Percansky, & Hans, 1987) by raters who resolved their disagreements on each item by consensus. Data on the reliability and validity for the PCOGS have been reported elsewhere (Bernstein, Hans & Percansky, 1991), as have findings from the present sample (Bernstein & Hans, 1994). For the present report risk was determined based on maternal PCOG scores summed across categories at each of the three ages and dichotomized at a mean split. Birth weight. Because prenatal opioid exposure has often been related to reduced birth weight, in particular intrauterine growth retardation, birth weight measured at the hospital was included as a covariate. short standard IMHJ (Wiley) RIGHT INTERACTIVE Infants Exposed to Opioid Drugs ● 307 RESULTS top of rh base of rh cap height base of text Simple Drug Effects To keep the total number of statistical tests to a minimum and maintain the integrity of the statistical protection levels, we employed repeated measures analyses. Huynh-Feldt epsilon statistics and associated p values were examined in each repeated measures analysis to insure that the assumptions for compound symmetry in repeated measures analyses were not being violated. Separate repeated-measures analyses of variance were computed on each of the five types of outcome variables (MDI, PDI, Attention Sum, Activity Level Sum, and Motor Coordination Sum) with age (five levels) as the repeated-measure and opioid exposure as the dichotomous independent variable. There were significant or marginally significant main effects for drug exposure for MDI, PDI, IBR Attention Sum, and IBR Motor Coordination Sum, but not the IBR Activity Level Sum. Opioid-exposed children had lower developmental scores, poorer motor coordination, and were less attentive. There were significant age effects on each of the five types of Bayley scores. Single degree of freedom polynomial tests of linear order were significant for each of the age effects. The two age-normed scores, MDI and PDI, dropped with age relative to norms. For the IBR scores, which are not formally age normed, attention and activity level increased, and motor problems decreased. There were no significant age by drug exposure interactions on any of the five analyses. Table 1 presents the Bayley child behavior means and standard deviations by drug group, and Table 2 presents the results of the repeated-measures ANOVAS. Cofactor Analyses We also analyzed effects on developmental outcomes of potentially confounding variables: use of four substances other than opioids, cumulative social-environmental risks, and birth weight. We first examined whether these five variables were related to maternal opioid usage. Table 3 presents the opioid group differences on these variables. Opioid-using mothers were, in fact, heavier users of tobacco, marijuana, and cocaine. The groups did not differ in terms of alcohol use; both groups were low consumers of alcohol. Moderate and heavy drinkers had been excluded from the comparison group and the opioid users tended not to drink heavily. Children exposed in utero had lower birth weights (although only two were born at less than 37 weeks gestational age). Opioid-using mothers had higher social-environmental risk scores (although they differed on only three of the nine individual items that made up the cumulative scores — adaptive functioning, stressors, and 24-month parenting). We next computed repeated-measures analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) on each of the four neurobehavioral outcome measures that had been related to maternal opioid usage (MDI, PDI, Attention Sum, Motor Coordination Sum) using opioid exposure as the primary grouping variable and tobacco, marijuana, alcohol, cocaine, social-environmental risk, and birth weight as covariates. In each of these analyses, preliminary analyses were conducted to determine whether the homogeneity of slopes assumption was violated by interaction effects between opioid exposure and any of the other cofactors. There were no such interaction effects. The results of these ANCOVAs for each outcome measure follow. MDI. With the inclusion of the covariates in the model, opioid exposure no longer had a significant effect on the repeated measures of the MDI. Only one of the covariates — socialenvironmental risk — showed a significant independent relation with MDI; more risk factors short standard IMHJ (Wiley) 308 ● LEFT INTERACTIVE top of rh base of rh S.L. Hans and R.J. Jeremy cap height base of text TABLE 1. Child Behavior Means and Standard Deviations by Age and Drug Group Age in Months Mental development index Opioid Comparison Psychomotor development index Opioid Comparison IBR attention sum Opioid Comparison IBR coordination problems Opioid Comparison IBR activity level sum Opioid Comparison 12 18 24 Mean Across Age 4 8 111 (12.3) 114 (15.1) 116 (19.5) 120 (20.2) 107 (14.3) 109 (13.7) 95** (16.3) 103 (13.1) 92 (12.7) 96 (12.3) 104* (7.8) 108 (8.3) 116 (12.5) 121 (12.3) 111 (12.4) 111 (12.4) 106 (18.0) 110 (17.7) 105 (17.6) 109 (17.8) 100* (14.2) 108 (14.9) 108 (9.2) 112 (10.4) 12.8 (3.9) 13.1 (4.2) 17.7 (2.1) 18.0 (2.6) 16.3** (2.8) 18.2 (2.7) 16.8 (2.5) 17.4 (2.5) 16.5 (3.1) 17.4 (2.5) 16.0* (1.4) 16.8 (1.6) 6.0 (1.1) 5.8 (1.1) 6.1 (1.2) 5.6 (1.2) 5.8 (1.2) 5.5 (0.9) 5.7 (1.0) 5.4 (1.1) 5.5** (1.2) 4.7 (1.3) 5.8** (0.7) 5.4 (0.7) 7.9* (1.8) 7.0 (1.4) 8.4 (1.8) 8.1 (1.5) 8.6 (1.3) 8.6 (1.7) 8.9 (1.5) 8.9 (1.8) 9.2 (1.5) 8.7 (1.7) 8.6 (1.0) 8.3 (1.0) * Univariate opioid effect p ⬍ .05. ** Univariate opioid effect p ⬍ .01. were associated with poorer MDI scores. Figure 1 plots cumulative social-environmental risk (uncorrected for other variables) by average MDI across the five ages. Using the regression line as an estimate, the difference between the fewest (0) and greatest (7) number of risk factors out of a possible nine amounted to approximately 10 points of the Mental Development Index, about two-thirds of a standard deviation. To explore whether particular components of the social-environmental risk index were more strongly related to MDI than others, similar repeated measures analyses were computed substituting each of the eight individual risk components for the cumulative score. In none of these analyses was an individual social-environmental risk factor a statistically significant predictor of MDI scores. PDI. With inclusion of the covariates, there was also no significant effect of opioid exposure on the PDI. Only one of the covariates — birth weight — showed a significant unique relation short standard IMHJ (Wiley) RIGHT INTERACTIVE Infants Exposed to Opioid Drugs 309 ● cap height base of text TABLE 2. Repeated Measures Analyses of Variance without and with Covariates MDI F(1,76) Opioid exposure Marijuana exposure Tobacco exposure Cocaine exposure Alcohol exposure Birth weight Social-environmental risk Repeated measure (age) 4.84* F(1,70) 0.05 0.86 0.24 0.07 1.87 0.04 4.29* PDI F(1,76) 3.25⫹ F(1,70) 0.37 0.41 2.16 0.52 1.92 3.77* 1.51 IBR Coordination IBR Attention Problems F(1,76) F(1,70) F(1,76) F(1,70) 5.21* 0.00 2.66 3.62⫹ 0.22 0.03 0.47 1.89 7.07* 1.57 0.49 0.04 0.29 0.38 2.83⫹ 0.94 top of rh base of rh IBR Activity F(1,76) F(1,70) 2.20 1.73 0.51 0.67 0.79 0.05 0.00 2.47 F(4,304) F(4,280) F(4,304) F(4,280) F(4,304) F(4,280) F(4,304) F(4,280) F(4,304) F(4,280) 36.99*** 0.33 14.80*** 2.51* 37.27*** 0.68 7.40*** 1.57 13.72*** 1.71 ⫹ p ⬍ .10. * p ⬍ .05. *** p ⬍ .001. TABLE 3. Differences between Opioid and Comparison Groups on Potential Confounding Variables Group Opioid Comparison n ⫽ 33 15 6 4 8 n ⫽ 45 36 5 4 0 Statistics 2(3) ⫽ 15.25** Marijuana exposure None Irregular Regular Heavy Tobacco exposure None ⬍ Pack per day ⱖ Pack per day 4 21 8 17 28 0 2(2) ⫽ 15.57*** Cocaine exposure None At least one time 20 13 45 0 2(2) ⫽ 21.3*** Alcohol exposure None Light/moderate Heavy 22 9 2 35 10 0 2(2) ⫽ 2.00 2922 3236 (592) (393) 3.49 1.87 (2.0) (1.2) Birth weight in grams (M and SD) Social-environmental risk (M and SD) ** p ⬍ .01. *** p ⬍ .001. t ⫽ 2.82** t ⫽ 4.21*** short standard IMHJ (Wiley) 310 ● LEFT INTERACTIVE S.L. Hans and R.J. Jeremy top of rh base of rh cap height base of text FIGURE 1. Scatterplot of social-environmental risk scores by mean Bayley MDI scores averaged across five ages. Circles signify infants exposed to opioid; squares signify comparison infants. Linear regression line plotted. with the repeated measures of PDI; lower birth weight was related to poorer PDI scores. Out of concern that these results might be unduly affected by the one child whose birth weight placed him in the the very low birth weight range, the MANCOVA was recomputed excluding that child, and results were similar. Figure 2 plots birth weight by mean PDI (uncorrected for other variables) across the five ages. Using the regression line as an estimate, each thousand grams of birth weight was associated with five PDI points. FIGURE 2. Scatterplot of birth weight by mean Bayley PDI scores averaged across five ages. Circles signify infants exposed to opioid; squares signify comparison infants. Linear regression line plotted. short standard IMHJ (Wiley) RIGHT INTERACTIVE Infants Exposed to Opioid Drugs ● 311 IBR sums. With inclusion of the covariates, there was also no significant effect of opioid exposure on the IBR Attention Sum, Motor Coordination Problems Sum, or Activity Level Sum. Prenatal tobacco exposure showed a trend to be related to poorer attention over age. top of rh base of rh cap height base of text DISCUSSION In the data presented, children whose mothers used opioid drugs during pregnancy showed significantly poorer mental and motor development during the first 2 years of life than did a group of demographically comparable children whose mothers had not used opioid drugs; opioid-exposed children performed more poorly on both mental and motor development and on both developmental scores and qualitative ratings scales. However, differences between the two groups were not large. Average developmental scores for children of drug-using women were within the normal range and only four points lower than for the comparison group, although these small lags were detected consistently across ages. Although IBR scores are not age-normed, the scores for infants in this sample are similar to those reported in the normative sample (Bayley, 1969). Even though small effects such as these can have major public health implications, they do not suggest cause for clinical concern in assessing the developmental potential of any individual infant (Lester, LaGasse, & Seifer, 1998). Although the data suggest that children with opioid-using mothers are at somewhat greater risk for poor mental and motor development during the first years of life than their peers whose mothers were not using drugs, they suggest that such lags are more strongly related to other factors associated with maternal drug use and that different risk factors may be influencing different domains of behavior. It appears that much of the effect of maternal opioid drug use on mental development of infant offspring is attributable to the experience of more social-environmental risk factors by children in substance-abusing families. Many of the social risk factors experienced by the opioid-exposed infants in the present sample were ones shared with the comparison group, but they also included a particularly high incidence of maternal psychopathology and insensitive parenting (Hans, 1999; Hans, Bernstein & Henson, 1999). Other studies have suggested that home environment may be the source of the relation between maternal drug use and child mental development (Azuma & Chasnoff, 1993; Johnson et al., 1987). The children in the present sample whose mothers used opioid drugs were more likely to experience multiple social-environmental risk than other low-income children, and this cumulation of risk factors was related to mental development as assessed on the Bayley Scales. In this sample, a composite of risk factors is a better predictor of functioning than any particular risk factor. Other studies of high-risk children have also found cumulative social-environmental risks to be more powerful predictors of early mental development than specific risk factors (Liaw & Brooks-Gunn, 1994; Sameroff et al., 1987). The impact of high-risk environments on children in this study was also reflected in the steady drop in mental performance during the second year of life by both groups of children relative to age adjusted norms. It is important to note that the decline over age in both groups of children from urban, low-income families was far greater than the differential performance related to opioid exposure. Numerous other studies exploring issues of poverty, low maternal education, and low birth weight have also reported similar patterns of slowed acquisition of mental developmental milestones beginning in the second year of life (cf. Aylward, 1992). A decline in Bayley MDI scores during the second year of life has been found in methadoneexposed and nonexposed groups in other samples (Johnson et al., 1984; Kaltenbach & Fin- short standard IMHJ (Wiley) 312 ● LEFT INTERACTIVE S.L. Hans and R.J. Jeremy negan, 1979; Wilson, 1989). It should be noted that the present study did not use the more recently normed Bayley Scales of Infant Development II (Bayley, 1993) for assessment. Whereas opioid exposure effects on MDI were attributable to social-environmental factors, we found opioid exposure effects on PDI and IBR ratings of motor coordination problems were mediated by birth weight. Other studies of drug-exposed children have suggested that some effects of prenatal exposure may be mediated by low birth weight (Brown, Bakeman, Coles, Sexson, & Demi, 1998; Lester et al., 1991;). It has been repeatedly documented in human and animal research that maternal opioid use is associated with decreased birth weight (Hans, 1992), and more so with intrauterine growth retardation than with prematurity. The mechanism by which opioids lead to reduced growth in some infants remains unclear, although evidence from preclinical studies suggests that it is probably not undernutrition (cf. Zagon & McLaughlin, 1992). Others have suggested that prenatal opioid exposure is associated with a reduction in organ cell number, rather than cell size, suggesting a mechanism early in pregnancy (Doberczak et al., 1987; Naeye, Blanc, Leblanc, & Khatamee, 1973). The present study offers little toward an understanding of causal factors involved in growth retardation associated with prenatal opioid exposure. However, that growth retardation in utero would be related specifically to neuromotor findings is consistent with others studies of infants affected by intrauterine growth retardation (Tomchek, Lane, & Ottenbacher, 1997). The data presented here suggest that maternal opioid use during pregnancy is associated with a variety of types of infant outcomes, and that in the absence of other social-environmental risk factors or low birth weight, maternal opioid use does not have a major impact on aspects of development assessed on standardized infant tests. The mental and motor development of opioid-exposed children — although slightly poorer than that of nonexposed and declining a little during the second year of life — still remains within the normal range of functioning during infancy. Altogether, our findings suggest that prenatal exposure to opioids under medically controlled conditions should not be a source of public alarm. On the other hand, our data do not address the risks of continued unsupervised opioid use throughout pregnancy, particularly when injected intravenously. In addition, mothers; methadone dose levels in the present study were considerably lower than those typically dispensed at methadone clinics currently (cf. D’Aunno, Folz-Murphy & Lin, 1999). Research has clearly documented that higher doses of methadone are more effective deterrents against relapse (Ball & Ross, 1991), and no research has documented whether higher levels of exposure are related to greater infant problems, as is typically the case for teratogenic substances (Vorhees, 1986). The present study, because it found little relation between cocaine and alcohol use with infant outcomes, should also not be used to conclude that use of these substances is safe during pregnancy, because usage levels in the present sample were very low, and quantification of them was relatively crude. Another limitation of the present study is its reliance on a standard developmental assessment tool. Because the Bayley Scales assess development from a variety of domains, it may not be as sensitive as other measures to teratological effects that are focused on particular functional abilities. Narrow-band tests are more likely to detect specific functional deficits, which in turn, will provide better information about the brain mechanisms underlying toxic exposures as well as potential interventions for helping children with such exposures (Jacobson & Jacobson, 1996). These data provide further evidence of the importance of the environment on child development. From a policy point of view, they suggest that focus should be placed both on increasing access to and quality of prenatal care for women who use drugs, and — critically important — complementing it by improving the rearing environments of their drug-exposed children. top of rh base of rh cap height base of text short standard IMHJ (Wiley) RIGHT INTERACTIVE Infants Exposed to Opioid Drugs ● 313 REFERENCES top of rh base of rh cap height base of text American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders–III— Revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Aylward, G.P. (1982). Methadone outcome studies: Is it more than the methadone? Journal of Pediatrics, 10, 214– 215. Aylward, G.P. (1992). The relationship between environmental risk and developmental outcome. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 13, 222–229. Azuma, S.D., & Chasnoff, I.J. (1993). Outcome of children prenatally exposed to cocaine and other drugs: A path analysis of three-year data. Pediatrics, 92, 396–402. Ball, J.C., & Ross, A. (1991). The effectiveness of methadone maintenance treatment. New York: Springer-Verlag. Bayley, N. (1969). Manual for the Bayley Scales of Infant Development. New York: Psychological Corporation. Bayley, N. (1993). Manual for the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (2nd ed.). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. Bernstein, V.J., & Hans, S.L. (1994). Predicting the developmental outcome of two-year-old children born exposed to methadone: The impact of social-environmental risk factors. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 23, 349– 359. Bernstein, V.J., Hans, S.L., & Percansky, C. (1991). Advocating for the young child in need through strengthening the parent– child relationship. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 20, 28–41. Bernstein, V.J., Percansky, C., & Hans, S.L. (1987, April). Screening for social-emotional impairment in infants born to teenage mothers. Paper presented at the biannual meeting of the society for Research in Child Development, Baltimore, MD. Blinick, G., Inturrisi, C.E., Jerez, E., & Wallach, R.C. (1975). Methadone assays in pregnant women and progeny. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 121, 617–621. Brazelton, T.B. (1973). Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale. Clinics in developmental medicine, No. 50. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott. Brown, J.V., Bakeman, R., Coles, C.D., Sexson, W.R., & Demi, A.S. (1998). Maternal drug use during pregnancy: Are preterm and full-term infants affected differently? Developmental Psychology, 34, 540– 554. Chasnoff, I.J., Hatcher, R., & Burns, W.J. (1982). Polydrug- and methadone-addicted newborns: A continuum of impairment? Pediatrics, 70, 210–213. D’Aunno, T., Folz-Murphy, N., & Lin, X. (1999). Changes in methadone treatment prctices: Results from a panel study. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 25, 681–699. Desmond, M.M., & Wilson, G.S. (1975). Neonatal abstinence syndrome: Recognition and diagnosis. Addictive Diseases, 2, 113– 121. Doberczak, T.M., Thorton, J.C., Berstein, J., & Kandall, S.R. (1987). Impact of maternal drug use dependency on birth weight and head circumference of offspring. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 141, 1163– 1167. Frank, B., & Galea, J. (1996). Cocaine trends and other drug trends in New York City, 1986–1994. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 15, 1– 12. Hans, S.L. (1989). Developmental consequences of prenatal exposure to methadone. In D.E. Hutchings (Ed.), Prenatal abuse of licit and illicit drugs. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 562, 195– 207. Hans, S.L. (1992). Maternal opioid drug use and child development. In I. Zagon & T. Slotkin (Eds.), Maternal substance abuse and the developing nervous system (pp. 177–213). New York: Academic Press. short standard IMHJ (Wiley) 314 ● LEFT INTERACTIVE S.L. Hans and R.J. Jeremy Hans, S.L. (1998). Developmental outcomes of prenatal exposure to alcohol and other drugs. In A.W. Graham & T.K. Schultz (Eds.), Principles of addiction medicine (2nd ed., pp. 1223–1237). Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine, Inc. top of rh base of rh cap height base of text Hans, S.L. (1999). Demographic and psychosocial characteristics of substance abusing pregnant women. Clinics in Perinatology, 26, 55– 74. Hans, S.L., Bernstein, V.B., & Henson, L.G. (1999). The role of psychopathology in the parenting of drug dependent women. Development and Psychopathology, 11, 957–977. Hollingshead, A.B., & Redlich, F.C. (1958). Social class and mental illness: A community study. New York: Wiley. Hutchings, D.E. (1985). Methadone: A treatment for drug addiction. New York: Chelsea House. Jacobson, J.J., & Jacobson, S.W. (1996). Methodological considerations in behavioral toxicology in infants and children. Developmental Psychology, 32, 390–403. Jeremy, R.J., & Hans, S.L. (1985). Behavior of neonates exposed in utero to methadone as assessed on the Brazelton scale. Infant Behavior and Development, 8, 323–336. Johnson, H.L., Diano, A., & Rosen, T.S. (1984). 24-month neurobehavioral follow-up of children of methadone-maintained mothers. Infant Behavior and Development, 7, 115–123. Johnson, H.L., Glassman, M.B., Fiks, K.B., & Rosen, T. (1987). Path analysis of variables affecting 36month outcome in a population of multi-risk children. Infant Behavior and Development, 10, 451– 465. Kaltenbach, K., & Finnegan, L.P. (1987). Perinatal and developmental outcome of infants exposed to methadone in-utero. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 9, 311–313. Kaltenbach, K., Graziani, L.J., & Finnegan, L.P. (1979). Methadone exposure in utero: Developmental status at one and two years of age. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior (Supplement), 11, 15–17. Kandall, S.R. (1998). Treatment options for drug-exposed neonates. In A.W. Graham & T.K. Schultz (Eds.), Principles of addiction medicine (2nd ed., pp.1211–1222). Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine, Inc. Kandall, S.R., Albin, S., Gartner, L.M., Lee, K.S., Eidelman, A., & Lowinson, J. (1977). The narcotic dependent mother: Fetal and neonatal consequences. Early Human Development, 1, 159–169. Kantrowitz, B. (1990, February 12). The crack children. Newsweek, pp. 62–63. Kinlock, T.W., Hanlon, T.E., & Nurco, D.N. (1998). Heroin use in the United States: History and present developments. In J.A. Inciardi & L.D. Harrison (Eds.), Heroin in the age of crack-cocaine (pp. 1– 30). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Lester, B.M., Corwin, M.J., Sepkoski, C., Seifer, R., Peucker, M., McLaughlin, S., & Golub, H.L. (1991). Neurobehavioral syndromes in cocaine-exposed newborn infants. Child Development, 62, 694–705. Lester, B.M., LaGasse, L.L., & Seifer, R. (1998). Cocaine exposure and children: The meaning of subtle effects. Science, 282, 633– 634. Liaw, F., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1994). Cumulative familial risks and low-birthweight children’s cognitive and behavioral development. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 23, 360–372. Marcus, J., & Hans, S.L. (1982). A methodological model to study the effects of toxins on child development. Neurobehavioral Toxicology and Teratology, 4, 483–487. Martin, M., Hecker, J., & Clark, R. (1991). China white epidemic: An eastern United States emergency department experience. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 20, 158–164. Matheny, A. P., Jr. (1980). Bayley’s Infant Behavior Record: Behavioral components and twin analyses. Child Development, 51, 1157– 1167. Musto, D.F. (1987). The American disease: Origins of narcotic control. New York: Oxford University Press. short standard IMHJ (Wiley) RIGHT INTERACTIVE Infants Exposed to Opioid Drugs ● 315 Naeye, R.L., Blanc, W., Leblanc, W., & Khatamee, M.A. (1973). Fetal complications of maternal heroin addiction: Abnormal growth, infections, and episodes of stress. Journal of Pediatrics, 83, 1055– 1061. top of rh base of rh cap height base of text Parinno, M.W. (Ed.). (1993). CSAT state methadone treatment guidelines. Treatment improvement protocol (TIP) (Series No. 1). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Payte, J.T. (1997). Methadone maintenance treatment: The first thirty years. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 29, 149– 153. Pierog, S. (1977). The infant in narcotic withdrawal: Clinical picture. In J.L. Rementeria (Ed.), Drug abuse in pregnancy and neonatal effects (pp. 95–102). St. Louis, MO: Mosby. Rosen, T.S. & Johnson, H.L. (1982). Children of methadone-maintained mothers: Follow-up to 18 months of age. Journal of Pediatrics, 101, 192–196. Sameroff, A.J., Seifer, R., Barocas, R., Zax, M., & Greenspan, S. (1987). Intelligence quotient scores of 4-year-old children: Social-environmental risk factors. Pediatrics, 79, 343–350. Strauss, M.E., Lessen-Firestone, J.K., Starr, R.H., & Ostrea, E.M., Jr. (1975). Behavior of narcotics addicted newborns. Child Development, 46, 887–893. Strauss, M.E., Starr, R.H., Ostrea, E.M., Jr., Chavez, C.J., & Stryker, J.C. (1976). Behavioral concomitants of prenatal addiction to narcotics. Journal of Pediatrics, 89, 842–846. Tomchek, S.D., Lane, S.J., & Ottenbacher, K. (1997). Pre-academic skill development in children who were full-term low-birthweight infants: Pilot data. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 17, 219– 236. Toufexis, A. (1991, May 13). Innocent victims. Time, 137(19), 56–60. University of Washington Pregnancy and Health Study. (1974). Pregnancy and health interview (adapted with permission of A.P. Streissguth). Seattle, WA: Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington. Vorhees, C.V. (1986). Origins of behavioral teratology. In C.V. Vorhees (Ed.), Handbook of behavioral teratology (pp. 3– 22). New York: Plenum. Wechsler, D. (1955). Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. New York: The Psychological Corporation. Wilson, G.S. (1989). Clinical studies of infants and children exposed prenatally to heroin. In D.E. Hutchings (Ed.), Prenatal abuse of licit and illicit drugs. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 562, 183– 194. Wilson, G.S., Desmond, M.M., & Wait, R.B. (1981). Follow-up of methadone-treated and untreated narcotic-dependent women and their infants: Health, developmental, and social implications. Journal of Pediatrics, 98, 716– 722. Zagon, I.S., & McLaughlin, P.J. (1984). An overview of the neurobehavioral sequelae of perinatal opioid exposure. In J. Yanai (Ed.), Neurobehavioral teratology (pp. 197–233). Elsevier: Amsterdam. Zagon, I.S., & McLaughlin, P.J. (1992). Maternal exposure to opioids and the developing nervous system: Laboratory findings. In I.S. Zagon & T.A. Slotkin (Eds.), Maternal substance abuse and the developing nervous system (pp. 241– 282). New York: Academic Press. Zelson, C., Rubio, E., & Wasserman, E. (1971). Neonatal narcotic addiction: 10 year observation. Pediatrics, 48, 178– 189. short standard