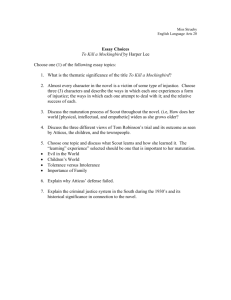

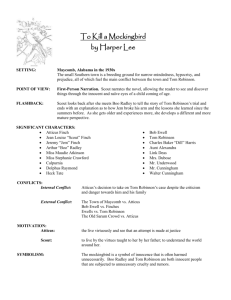

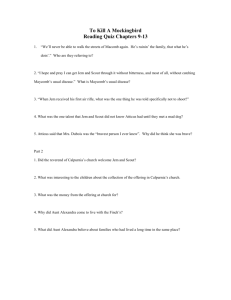

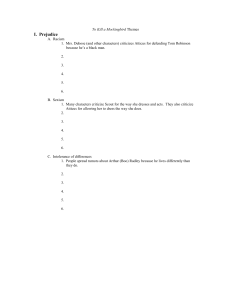

To Kill a Mockingbird

advertisement