Strategic Plan for Texas Public Community Colleges

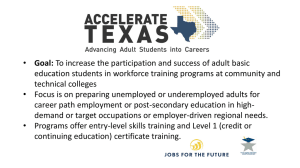

advertisement