Are we a family or a business? - Price Theory

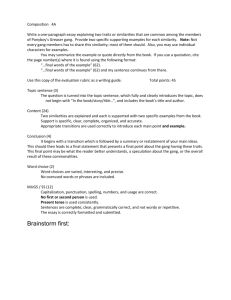

advertisement