Deviant Cadential Six-Four Chords

advertisement

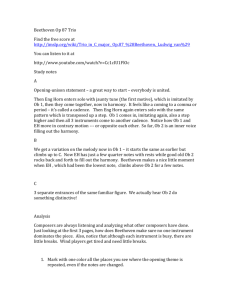

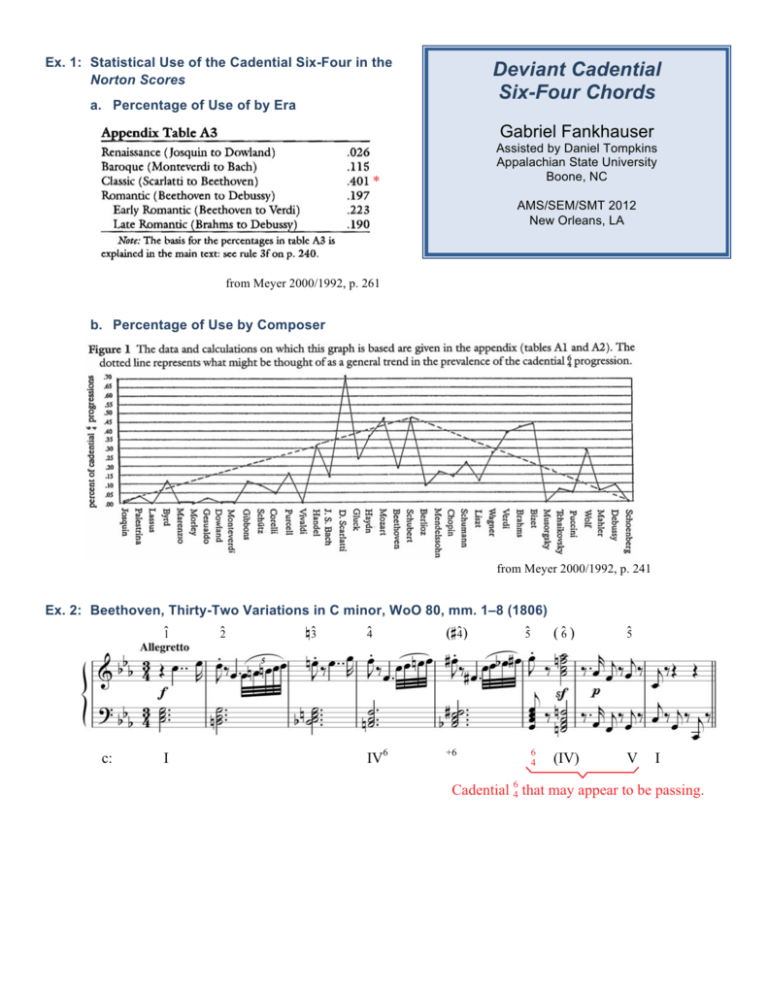

Ex. 1: Statistical Use of the Cadential Six-Four in the Norton Scores Deviant Cadential Six-Four Chords a. Percentage of Use of by Era Gabriel Fankhauser Assisted by Daniel Tompkins Appalachian State University Boone, NC * AMS/SEM/SMT 2012 New Orleans, LA from Meyer 2000/1992, p. 261 b. Percentage of Use by Composer from Meyer 2000/1992, p. 241 Ex. 2: Beethoven, Thirty-Two Variations in C minor, WoO 80, mm. 1–8 (1806) 1̂ c: I 2̂ n3̂ 4̂ IV6 (s4̂) +6 5̂ 6 4 ( 6̂ ) 5̂ (IV) V I Cadential 64 that may appear to be passing. Ex. 3: Beethoven, Piano Sonata No. 4 in Ef , Op. 7, III, mm. 1–17 (1797) Ef: I 8—7 I V6 — 5 I 4—3 6 — 7 I4 (vii° /vi) vi (V65/V) V 1. Follows tonic. Note also the apparent six-fours on the downbeats of mm. 9 and 10. 6 2. Bass moves after 4, eliding the dominant (locally, at least). Ex. 4: Beethoven, “Pathétique” Sonata, I, mm. 132–135 (1798) g: i vii°7/V V vii°42 — 43 i6 vii°42 — 43 = e: vii°7 — 42 V64 — 7 – 64 — 7 (V7 – 64 — 7 — 64 —– 7 ?) 6 Cadential 4 falls on weak beat. Ex. 5: Beethoven, “Waldstein” Sonata, I, mm. 35–43 (1804) ——— 7 V 86 — 5 E: I 4—3 8 ——— 3 7 V 64 — —5 I Sixth and fourth resolve upward (cf. m. 37). Ex. 6: Mozart, Concerto in D for Horn, K. 412, I, mm. 26–29 6 4, 6 underlying an inverted cadential 4 From Rothstein 2006, 277, Ex. 24 Ex. 7: Phish, “Poor Heart” (Picture of Nectar, Elektra 1992) Hypermeter: 1 2 3 4, 1 G: I – – V, I 2 3 4 G – D, G G7/B C C#°7 G D G You won’t steal my poor heart again. (R) You won’t steal my tape recorder. I’ll call the Lord, and he’ll put you in the pen. You won’t steal that thing again. V65/IV vii°7/V I IV V7 I Inverted 64 Ex. 8: Radiohead, “2+2=5” (Hail to the Thief, Capitol 2003) 1 2 3 4, 1 2 3 (3) 4 (4) 7 (7 or 9) Fm Csus/E Fm Csus/E Fm Csus/E F/Ef D7 Gm Fm C/E Are you such a dreamer to put the world to rights? I’ll stay home for- ever, where two and two always makes a five. — I’ll lay down the tracks, sandbag, and hide. January has April showers, and two and two always makes a five. — f: i (V6) i (V6), i N (not cadential “64”) V6 V42/iv V7/ii ii i V6 – Inverted 64 and inverted V. Ex. 9: Definition of Cadential Six-Four and Deviations Defining characteristics of cadential six-four Deviation Deviant Examples 1. Approach: Follows dominant or tonic harmony Weak beat (rarest deviation?) 6–7 Resolution is upward: 4–5 Beethoven, “Pathétique” Sonata, I, m. 134 (cf. m. 135) Beethoven, “Pathétique” Sonata, I, m. 134 Inverted six-fours: I6 – V I–V 6 Bass changes: 4 –(IV)– V Mozart, Concerto in D for Horn, K. 412, I, m. 28 Phish, “Poor Heart;” Radiohead, “2+2=5” Beethoven, Thirty-Two Variations in C minor Beethoven, Piano Sonata in Ef, Op. 7, III, m. 11 Radiohead, “2+2=5” Beatles, “Julia” Follows pre-dominant harmony (neither V nor vii°, nor I?) 2. *Accentuation: Strong beat or more accented than resolution to V 6–5 th 3. Resolution: 6 and 4th resolve down by step, 4–3 4. *Intervals: 6th and 4th above bass 5. *Bass Departure: Subsequent bass note is dominant (5̂) 6 4 –(vii°7/vi)– vi I–V 6. Bass Note: Dominant (5̂) 6 6 Other bass notes: iii4 – V 6 fVI4 6 fI4 6 fffI4 7. *Tonic Pitches: Contains members of the tonic triad (1̂, 3̂, and 5̂) Chromatic displacement: 8. Function: “Plagal” cadential 6 6 six-fours?: IV4 and ii4 Dominant (V), with delay of leading tone (7̂) Beethoven, “Waldstein” Sonata, I, m. 41 Liszt, “Il penseroso,” m. 7 Prokofiev, Symphony No. 1, III, m. 10 Shostakovich, Prelude, Op. 34, No. 10, m. 15 Debussy, “La fille aux cheveux de lin,” m. 15 and m. 35 * Most essential criteria (2, 4, 5, and 7). For a conventional example that satisfies all criteria above, see Beethoven “Waldstein” Sonata, m. 38 (above). Also, melodic line: 3̂–2̂–1̂ is most definitive and common, but also possible are 1̂–7̂–1̂, 5̂–4̂–3̂, etc. Ex. 10: Contrapuntal vs. Harmonic Means for Deviation 1. Counterpoint: Tonic pitches (from “I”) remain while figured bass (inversion) varies. I 6 4 or 2. Harmony: Six-four intervals remain while triadic spelling or pitch collection varies. NOTE: All cases preserve underlying syntactical role and dominant function. Ex. 11: Cadential Six-Fours of Increasing Deviance a. b. c. 8–7 I IV6 V64 –– 53 I d. I6 V 7 I conventional … e. I V7 I … contrapuntal deviations… III64 V7 I 6 fiii4 … harmonic deviations… … bizarre Ex. 12: Beatles, “Julia” (The Beatles [White Album], Capitol 1968) 1 2 3 D: I vi (iii4) D Bm7 Fsm/Cs Half of what I say is meaningless, 4, 1 2 3 I vi iii4 D Bm7 Fsm/Cs but I say it just to reach you, Ju— 6 Passing 6 4 6 (&) A li— 4=1 D a/Julia (vocal overdub) V I 6 Altered cadential 4 V7 I Ex. 13: Liszt, Année de pélerinage (Years of Pilgrimage): Italia, 2. “Il penseroso” (1839), mm. 1–9 cs: 6 6 fvi i ivø7 fvi i fVI4 = e: iv6 f9 V76 – 5 i f9 V74 – 3 i Altered (“wrong”) cadential 64 Ex. 14: Reduction, Voice-Leading Analysis, and Normalization of mm. 1–8 a. Reduction f9 cs: i fvi ivø7 V76 – 5 i , i 6 fvi = e: iv6 6 fVI4 f9 V74 – 3 i b. Voice-Leading Analysis 6 4 c. Normalized Reduction cs: i VI iv 7 f9 7 V6 – 5 i, i 6 VI = E: IV6 V 8—9 8—7 6—5 4 ——— 3 I Ex. 15: Prokofiev, “Classical” Symphony, Op. 25, III, mm. 1–12 (1917) Not neighboring but altered (“wrong”) cadential 64, “fI64.” Ex. 16: Voice-Leading Analysis and Normalization of mm. 9–12 a. Voice-Leading Analysis b. Normalization Hypothetical “Shadow” Shadow D: I Gr+6 V64 —————————— G V7 From Fankhauser 2006, 204–205 (Exx. 10-2 and 10-3) I Ex. 17: Shostakovich, Piano Prelude, Op. 34, No. 10 (1932–33), mm. 1–18 As/Bf Problem Altered (“wrong”) cadential 64, “fffI64.” Ex. 18: Voice-Leading Analysis of mm. 1–18 Ex. 19: Shostakovich, Piano Prelude, Op. 34, No. 10 (1932–33), mm. 38–end cs: I V7 Ex. 20: Voice-Leading Analysis of mm. 39–53 Use of inverted 64 as a conventional term with new meaning: irony. From Fankhauser (forthcoming in Music Analysis) Bibliography Bass, Richard. 1988. “Prokofiev’s Technique of Chromatic Displacement.” Music Analysis 7/2: 197–214. Beach, David. 1992. “The Cadential Six-four as Support for Scale-Degree Three of the Fundamental Line.” Journal of Music Theory 34/1: 81–99. _____. 1990. “More on the Six-Four.” Journal of Music Theory 34/2: 281–290. _____. 1967. “The Functions of the Six-Four Chord in Tonal Music.” Journal of Music Theory 11/1: 2–31. Brown, Matthew. 1986. “The Diatonic and the Chromatic in Schenker’s Theory of Harmonic Relations.” Journal of Music Theory 30/1: 1–33. Burstein, L. Poundie. 1999. “Comedy and Structure in Haydn’s Symphonies.” In Schenker Studies 2, ed. Carl Schachter and Hedi Siegel, 67–81. New York: Cambridge University Press. Cadwallader, Allen. 1992. “More on Scale Degree Three and the Cadential Six-Four.” Journal of Music Theory 36/1: 187–198. Cohn, Richard. 2012. Audacious Euphony: Chromaticism and the Triad’s Second Nature. New York: Oxford University Press. Cone, Edward T. 1972. “Stravinsky: The Progress of a Method.” In Perspectives on Schoenberg and Stravinsky. ed. Benjamin Boretz and Edward T. Cone. New York: W. W. Norton. Cutler, Timothy. 2009. “On Voice Exchanges.” Journal of Music Theory 53/2: 191–226. Damschroder, David. 2008. Thinking about Harmony: Historical Perspectives on Analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press. Drabkin, William. 1996. “Schenker, the Consonant Passing Note, and the First-Movement Theme of Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 26.” Music Analysis 15/2/3: 149–189. Everett, Walter. 2004. “Making Sense of Rock’s Tonal Systems.” Music Theory Online 10/4. Fankhauser, Gabriel. [Forthcoming in 2013]. “Cadential Intervention and Its Meaning in the Finale of Shostakovich’s Piano Trio in E Minor, Op. 67.” Music Analysis [32]. _____. 2006. “Flat Primary Triads, Harmonic Refraction, and the Harmonic Idiom of Shostakovich and Prokofiev.” In Musical Currents from the Left Coast, ed. Bruce Quaglia and Jack Boss, 202–215. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Forte, Allen and Steven E. Gilbert. 1982. Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis. New York: W. W. Norton. _____. 1982. Solutions to Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis. New York: W. W. Norton. Gjerdingen, Robert O. 2009. “Meyer and Music Usage.” Musica Humana 1: 197–224. _____. 2007. Music in the Galant Style. New York: Oxford University Press. Goldenberg, Yosef. 2006. “A Musical Gesture of Growing Obstinacy.” Music Theory Online 12/2. Kramer, Jonathan D. 1988. Listen to the Music: A Self-Guided Tour through the Orchestral Repertoire. New York: Schirmer Books. _____. 1987. “Questions about the Ursatz: A Response to Neumeyer.” In Theory Only 10/4: 11–31. Lester, Joel. 1992. “Reply to David Beach.” Journal of Music Theory 36/1: 199–206. Meyer, Leonard B. 2000 [1992]. “Nature, Nurture, and Convention: The Cadential Six-Four Progression.” In The Spheres of Music: A Gathering of Essays, 226–261. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Minturn, Neil. 1997. The Music of Sergei Prokofiev. New Haven: Yale University Press. Neumeyer, David. 1987. “The Three-Part Ursatz.” In Theory Only 10/1/2: 3–29. _____. 1987. “The Urlinie from 8 as a Middleground Phenomenon.” In Theory Only 9/5/6: 3–25. Rothstein, William. 2006. “Transformation of Cadential Formulae in the Music of Corelli and his Successors.” In Essays from the Third International Schenker Symposium, ed. Allen Cadwallader, 245–278. New York: Georg Olms. Schachter, Carl. 1990. “Either/Or.” In Schenker Studies, Edited by Hedi Siegel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Wen, Eric. 1999. “Bass-Line Articulations of the Urlinie.” In Schenker Studies 2, ed. Carl Schachter and Hedi Siegel, 276–97. New York: Cambridge University Press.