The Haymarket Square Riot

advertisement

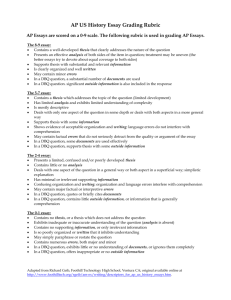

Debating the Documents Interpreting Alternative Viewpoints in Primary Source Documents The Haymarket Square Riot Were the Haymarket defendants completely innocent victims or were they partly to blame for their fate? ©2006 MindSparks, a division of Social Studies School Service 10200 Jefferson Blvd., P.O. Box 802 Culver City, CA 90232 United States of America (310) 839-2436 (800) 421-4246 Fax: (800) 944-5432 Fax: (310) 839-2249 http://mindsparks.com access@mindsparks.com Permission is granted to reproduce individual worksheets for classroom use only. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-57596-227-6 Product Code: HS478 Teacher Introduction Teacher Introduction Using Primary Sources Primary sources are called “primary” because they are firsthand records of a past era or historical event. They are the raw materials, or the evidence, on which historians base their “secondary” accounts of the past. A rapidly growing number of history teachers today are using primary sources. Why? Perhaps it’s because primary sources give students a better sense of what history is and what historians do. Such sources also help students see the past from a variety of viewpoints. Moreover, primary sources make history vivid and bring it to life. However, primary sources are not easy to use. They can be confusing. They can be biased. They rarely all agree. Primary sources must be interpreted and set in context. To do this, students need historical background knowledge. Debating the Documents helps students handle such challenges by giving them a useful framework for analyzing sources that conflict with one another. “Multiple, conflicting perspectives are among the truths of history. No single objective or universal account could ever put an end to this endless creative dialogue within and between the past and the present.” From the 2005 Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct of the Council of the American Historical Association. The Haymarket Square Riot | Debating the Documents 3 Teacher Introduction The Debating the Documents Series Each Debating the Documents booklet includes the same sequence of reproducible worksheets. If students use several booklets over time, they will get regular practice at interpreting and comparing conflicting sources. In this way, they can learn the skills and habits needed to get the most out of primary sources. Each Debating the Documents Booklet Includes ... • Suggestions for the Student and an Introductory Essay. The student gets instructions and a one-page essay providing background on the booklet’s topic. A time line on the topic is also included. • TWO Groups of Contrasting Primary Source Documents. In most of the booklets, students get one pair of visual sources and one pair of written sources. In some cases, more than two are provided for each. Background is provided on each source. Within each group, the sources clash in a very clear way. (The sources are not always exact opposites, but they do always differ in some obvious way.) • Three Worksheets for Each Document Group. Students use the first two worksheets to take notes on the sources. The third worksheet asks which source the student thinks would be most useful to a historian. • CD-ROM. The ImageXaminer lets students view the primary sources as a class, in small groups, or individually. A folder containing all of the student handouts in pdf format, including a graphic organizer for use with the ImageXaminer’s grid tool, allows for printing directly from the CD. • One DBQ. On page 22, a document-based question (DBQ) asks students to write an effective essay using all of the booklet’s primary sources. How to Use This Booklet All pages in this booklet may be photocopied for classroom use. 1. Have students read “Suggestions for the Student” and the Introductory Essay. Give them copies of pages 7–9. Ask them to read the instructions and then read the introductory essay on the topic. The time line gives them additional information on that topic. This reading could be done in class or as a homework assignment. 2. Have students do the worksheets. Make copies of the worksheets and the pages with the sources. Ask students to study the background information on each source and the source itself. Then have them take notes on the sources using the worksheets. If students have access to a computer, have them review the primary sources with the ImageXaminer. You may also ask them to use its magnifying tools to more clearly focus their analysis. 4 Debating the Documents | The Haymarket Square Riot Teacher Introduction 3. “Debate the documents” as a class. Have students use their worksheet notes to debate the primary source documents as a class. Use the overheads to focus this discussion on each source in turn. Urge students to follow these ground rules: • Use your worksheets as a guide for the discussion or debate. • Try to reach agreement about the main ideas and the significance of each primary source document. • Look for points of agreement as well as disagreement between the primary sources. • Listen closely to all points of view about each primary source. • Focus on the usefulness of each source to the historian, not merely on whether you agree or disagree with that source’s point of view. 4. Have students do the final DBQ. A DBQ is an essay question about a set of primary source documents. To answer the DBQ, students write essays using evidence from the sources and their own background knowledge of the historical era. (See the next page for a DBQ scoring guide to use in evaluating these essays.) The DBQ assignment on page 22 includes guidelines for writing a DBQ essay. Here are some additional points to make with students about preparing to write this kind of essay. The DBQ for this Booklet (see page 22): The Haymarket anarchists often discussed the use of violence for political purposes. Even if they were innocent of the Haymarket bombing, were their critics right to see them as a danger to Chicago and the nation? Why or why not? • Analyze the question carefully. • Use your background knowledge to set sources in their historical context. • Question and interpret sources actively. Do not accept them at face value. • Use sources meaningfully to support your essay’s thesis. • Pay attention to the overall organization of your essay. The Haymarket Square Riot | Debating the Documents 5 Teacher Introduction Complete DBQ Scoring Guide Use this guide in evaluating the DBQ for this booklet. Use this scoring guide with students who are already familiar with using primary sources and writing DBQ essays. Excellent Essay • Offers a clear answer or thesis explicitly addressing all aspects of the essay question. • Does a careful job of interpreting many or most of the documents and relating them clearly to the thesis and the DBQ. Deals with conflicting documents effectively. • Uses details and examples effectively to support the thesis and other main ideas. Explains the significance of those details and examples well. • Uses background knowledge and the documents in a balanced way. • Is well written; clear transitions make the essay easy to follow from point to point. Only a few minor writing errors or errors of fact. Good Essay • Offers a reasonable thesis addressing the essential points of the essay question. • Adequately interprets at least some of the documents and relates them to the thesis and the DBQ. • Usually relates details and examples meaningfully to the thesis or other main ideas. • Includes some relevant background knowledge. • May have some writing errors or errors of fact, as long as these do not invalidate the essay’s overall argument or point of view. Fair Essay • Offers at least a partly developed thesis addressing the essay question. • Adequately interprets at least a few of the documents. • Relates only a few of the details and examples to the thesis or other main ideas. • Includes some background knowledge. • Has several writing errors or errors of fact that make it harder to understand the essay’s overall argument or point of view. Poor Essay • Offers no clear thesis or answer addressing the DBQ. • Uses few documents effectively other than referring to them in “laundry list” style, with no meaningful relationship to a thesis or any main point. • Uses details and examples unrelated to the thesis or other main ideas. Does not explain the significance of these details and examples. • Is not clearly written, with some major writing errors or errors of fact. 6 Debating the Documents | The Haymarket Square Riot Student SUGGESTIONS Suggestions to the Student Using Primary Sources A primary source is any record of evidence from the past. Many things are primary sources: letters, diary entries, official documents, photos, cartoons, wills, maps, charts, etc. They are called “primary” because they are first-hand records of a past event or time period. This Debating the Documents lesson is based on two groups of primary source documents. Within each group, the sources conflict with one another. That is, they express different or even opposed points of view. You need to decide which source is more reliable, more useful, or more typical of the time period. This is what historians do all the time. Usually, you will be able to learn something about the past from each source, even when the sources clash with one another in dramatic ways. How to Use This Booklet 1. Read the one-page introductory essay. This gives you background information that will help you analyze the primary source documents and do the exercises for this Debating the Documents lesson. The time line gives you additional information you will find helpful. 2. Study the primary source documents for this lesson. For this lesson, you get two groups of sources. The sources within each group conflict with one another. Some of these sources are visuals; others are written sources. With visual sources, pay attention not only to the image’s “content” (its subject matter), but also to its artistic style, shading, composition, camera angle, symbols, and other features that add to the image’s meaning. With written sources, notice the writing style, bias, even what the source leaves out or does not talk about. Think about each source’s author, that author’s reasons for writing, and the likely audience for the source. These things give you clues as to the source’s historical value. 3. Use the worksheets to analyze each group of primary source documents. For each group of sources, you get three worksheets. Use the “Study the Document” worksheets to take notes on each source. Use the “Comparing the Documents” worksheet to decide which of the sources would be most useful to a historian. 4. As a class, debate the documents. Use your worksheet notes to help you take part in this debate. 5. Do the final DBQ. “DBQ” means “document-based question.” A DBQ is a question along with several primary source documents. To answer the DBQ, write an essay using evidence from the documents and your own background history knowledge. The DBQ is on page 22. The Haymarket Square Riot | Debating the Documents 7 Introductory ESSAY • The Haymarket Square Riot • It was evening, May 4, 1886. In Chicago’s Haymarket Square, two or three thousand workers had gathered. They listened as speakers protested police shootings at a riot at the McCormick Harvester plant the day before. The last Haymarket speaker was just finishing up. Only a few hundred people remained when police on horseback moved in and ordered everyone to leave. Suddenly, someone threw a bomb. It exploded. Police began shooting. People screamed and fled. Seven policemen and at least four workers died. An eighth policeman died of his wounds much later. Long before 1886, Chicago had become a tense, deeply divided city. After the Civil War, it grew rapidly, even uncontrollably. Tens of thousands of workers labored long hours for low pay in its factories, warehouses, and stockyards. A huge demand for laborers made Chicago a magnet pulling in immigrants from Germany, Ireland, Poland, Italy, and many other nations. As they struggled to find their way in a strange land, they often met with suspicion and hostility. Many native-born Chicagoans saw these immigrants as a threat to social order and a more traditional way of life. Struggles to organize unions often brought these tensions to the surface. Powerful business owners fought bitterly to keep the unions out. In the 1870s and ‘80s, several strikes led to riots and violent clashes between the police and the workers. The Haymarket bombing itself took place at the high point of a national movement for the eight-hour workday. The Chicago newspapers generally backed the owners in such labor battles. The press often depicted union organizers as dangerous, foreign-born radicals who were merely using the workers to bring about a violent socialist revolution. Clerks, professionals, small business owners, and other middle-class Chicagoans knew little about the radical ideas brought to Chicago by German or other foreign-born socialists and anarchists. What they did know was that these 8 Debating the Documents | The Haymarket Square Riot radicals always seemed to be stirring up trouble among the city’s workers. Their fears were not entirely unreasonable. Some radicals, foreign and native-born, did call for revolution. And at times, they did seem to glorify the use of violence to bring it about. In anarchist newspapers such as the German Arbeiter-Zeitung or the English language paper The Alarm, some writers seemed almost glowing in their view that dynamite could be the great equalizer in the war between the bosses and the workers. Following the Haymarket bombing, terrified Chicagoans directed their rage at the anarchist leaders of the Haymarket protest. Eight of those leaders were convicted of inciting the violence, even though none were linked to the bomb or the bomb thrower. Four were hung. One committed suicide. Most historians agree that the Haymarket trial was deeply flawed. Witnesses were highly unreliable. The judge was openly hostile to the defendants. Only people already suspicious of the anarchists were allowed on the jury. In 1893, after tempers had cooled somewhat, a reform-minded governor pardoned the remaining three Haymarket defendants still in jail. From the four documents provided here, you will NOT be able to decide the innocence or guilt of the anarchists on trial. Instead, these documents will help you understand the ideas of the anarchists and the views of their critics. Your task is not to act as a jury in what was clearly an unjust trial. Instead, it is to understand the radicalism of the late 1800s and the views of those opposed to it. The documents should help you debate the larger meaning of Haymarket to Chicago and the nation at that time. A Haymarket Square TIME LINE A Haymarket Sqaure Time Line 1869 The first transcontinental railroad is completed. Chicago begins its rapid growth as a major industrial city. Uriah Stephans organizes a new union known as the Knights of Labor. 1873 The Panic of 1873 is followed by several years of economic hard times. 1877 A railroad strike protesting recent wage cuts spreads to many railroads and large cities. Widespread violence occurs. Federal troops are called out when some state militias side with the strikers. 1883 Anarchists August Spies and Albert Parsons are among the radicals who organize the International Working People’s Association and issue the “Pittsburgh Manifesto.” It calls for the “destruction of the existing class rule, by all means.” 1884 The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions passes a resolution calling for an eight-hour work day by May 1, 1886. 1885 The Knights of Labor lead a successful strike against railroad tycoon Jay Gould. Membership in the Knights soars (including in Chicago). 1886 March. Knights of Labor unions lead more than 200,000 workers in another huge strike against two railroads owned by Jay Gould. Clashes occur between strikers and Pinkerton detectives working for Gould. State militias are brought in, sparking even more violence. May 1. Workers across the nation rally to demand the eight-hour day. Albert Parsons helps lead 80,000 members of the Knights of Labor and other workers in a march down Michigan Avenue in Chicago. May 3. At the McCormick Reaper Works a strike turns violent and police kill four people. Some anarchists and others meet that night to plan a protest the next day in Haymarket Square. May 4. At the Haymarket rally, Spies, Parsons, and Samuel Fielden speak. As the rally is ending, police move in to urge people to leave. A bomb is thrown, police begin firing, and several people are killed. May 5. In the hysteria following the Haymarket bombing, many radicals are rounded up. Eight will ultimately go on trial. June 21–October 9. The Haymarket defendants are tried and found guilty. Seven are sentenced to death. November–December. The Knights especially are harshly blamed for the troubles in Chicago. Their great railroad strike had petered out that summer. Membership plunges as many leave to join the new American Federation of Labor. 1887 On November 11, Spies, Parsons, Adolph Fischer, and George Engel are hanged. The evening before, a fifth defendant, Louis Lingg, committed suicide in prison. 1893 Reformist Governor John Peter Altgeld pardons Fielden, Oscar Neebe, and Michael Schwab after deciding all eight defendants were innocent. The Haymarket Square Riot | Debating the Documents 9 First Group of Documents DOCUMENT 1 Visual Primary Source Document 1 Courtesy of the Library of Congress Information on Document 1 Thomas Nast was one of the most famous American editorial cartoonists of the late 1800s. This cartoon of his appeared in the national news magazine Harper’s Weekly shortly after the verdict was handed down in the trial of the Haymarket anarchists. Harper’s Weekly covered the Haymarket riot and bombing heavily. It was relentlessly hostile toward the anarchists, depicting them as a grave danger to the republic. 10 The female figure shown here was often used in political cartoons to stand for justice or for the nation united in a just cause. Nast shows only the figure’s powerful hands. One of these hands has grasped the wriggling and helpless Haymarket defendants. The hand holding the sword has a wedding band labeled “UNION.” This female figure may also suggest the Statue of Liberty newly arrived in New York Harbor. Debating the Documents | The Haymarket Square Riot First Group of Documents DOCUMENT 2 Visual Primary Source Document 2 Courtesy of the Library of Congress Information on Document 2 German immigrant August Spies was a key anarchist leader, editor of the ArbeiterZeitung and a defendant in the Haymarket trial. to speak at the rally unless these words were removed. Fischer agreed to this, and the result was a second version of the handbill, the one on the right. On the morning of May 4, he agreed to speak at the Haymarket meeting set for that evening. Later, at the Arbeiter-Zeitung, he noticed a handbill calling on workers to attend the meeting. It is the one on the left here. It was prepared by another Haymarket defendant, Adolph Fischer. Spies objected to the line "Workingmen Arm Yourselves and Appear in Full Force." He told the Haymarket jury that he refused The corrected handbill was the main one used, but a few uncorrected ones were also distributed. Prosecutors said the uncorrected handbills proved that the anarchists planned violence. But Fischer said he put the “Arm Yourselves” line in only “because I didn't want the workingmen to be shot down in that meeting as on other occasions.” The Haymarket Square Riot | Debating the Documents 11 Study the Document First group of documents Study the Document: Visual Source 1 Instructions: Take notes on these questions. Use your notes to discuss the documents and answer the DBQ. 1 Main Idea or Topic In your own words, explain what the cartoon’s four-word caption means and what it has to do with the Haymarket bombing. 2 Context In addition to the Haymarket bombing, what else do you need to know about to understand this document? Why do you think the entire nation in the 1880s was so concerned about this tiny group of anarchists in Chicago? 3 Bias What opinion of the anarchists does this cartoon seem to express? 4 Visual Features Why do you think the artist focused only on the female figure’s hands? How does this focus add to the cartoon’s impact? What other visual features express its meaning and point of view? 5 Usefulness This illustration does express a clear bias. Could a historian still use this document as evidence of some sort? If so, does its bias add to its usefulness as a primary source or make it less useful? Explain your answers. 12 Debating the Documents | The Haymarket Square Riot Study the Document First group of documents Study the Document: Visual Source 2 Instructions: Take notes on these questions. Use your notes to discuss the documents and answer the DBQ. 1 Main Idea or Topic Briefly describe these two documents and explain what their main purpose was. 2 Context The two handbills taken together are important to any understanding of the Haymarket bombing and trial. From what you know about the bombing and the trial, can you explain why? What else about Chicago or the nation at the time helps explain what you see in these handbills? 3 Visual Features These handbills are made up only of words. Yet the way they are designed does help add to their meaning. What design features (typefaces, type sizes, arrangements of words, etc.) help add to their impact? 4 Usefulness What use could a historian make of these two handbills taken together? What use, if any, could a historian make if only one of the handbills existed? The Haymarket Square Riot | Debating the Documents 13 Comparing the DOCUMENTS Comparing the Documents The Visual Sources Answer the question by checking one box below. Then complete the statements on the Comparison Essay worksheet. Use all your notes to help you take part in an all-class debate about these documents—and to answer the final DBQ for the lesson. Which of these two primary source documents would be most useful to a historian trying to understand the Haymarket riot? (In this case, “Document 2” means both handbills.) Document 1 14 Debating the Documents | The Haymarket Square Riot Document 2 Comparing the DOCUMENTS Comparison Essay I chose Document ______ because: _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ I did not choose Document ______. However, a historian still might use the document in the following way: _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ KEEP THIS IN MIND: Some sources are very biased. A biased source is one that shows you only one side of an issue. That is, it takes a clear stand or expresses a very strong opinion about something. A biased source may be one-sided, but it can still help you to understand its time period. For example, a biased editorial cartoon may show how people felt about an issue at the time. The usefulness of a source depends most of all on what questions you ask about that time in the past. The Haymarket Square Riot | Debating the Documents 15 Second Group of Documents DOCUMENT 1 Written Primary Source Document 1 Information on Document 1 On September 14, 1887, the Illinois Supreme Court upheld the convictions of the Haymarket anarchists. The national news magazine Harper’s Weekly very strongly favored this decision. These passages are from its October 1, 1887, editorial praising the state court and explaining exactly why the Haymarket defendants were guilty even though they were not linked directly to the bomb or the bomb thrower.The first paragraph here refers to one of the convicted anarchists, Albert Parsons, who turned himself in the day the trial began. • Document 1 • Parsons surrendered himself for trial unquestionably because he supposed that the actual thrower of the bomb could not be identified, and therefore that no criminal connection could be established between the speeches and writings and plans of the anarchists and the fatal act. That was the feeling of some other observers, who have been inclined to think that the anarchists were really tried for their opinions, and in the event of their execution, would be regarded as martyrs of free speech. But even upon the showing of the summary of the trial published by their own friends, it is almost impossible not to hold the anarchists legally and morally guilty of the crime. The meetings, the justification of force, the appeal to force, the manufacture of the bombs for a purpose, the call to arms after the riot at McCormack’s, the determination to resist the police as myrmidons of bloody capital, the Haymarket meeting, the harangues, the approach of the police, and the catastrophe are all inextricably connected and are all steps toward the crime. Anarchy contemplates a forcible subversion of society, which must begin, if at all, in the very way that was adopted at Chicago ... 16 In the commission of such crimes it is those who instill the idea in more ignorant minds, those who justify the deed, who point out the criminal means, and who inflame murderous passions to the utmost, who are morally guilty. During the last two years there has been enormous suffering among honest laboring men and women, produced by strikes under a hundred pretexts. Now is it the unhappy and terrorized men who have obeyed despotic leaders, or is it the leaders themselves, who are really responsible for all the suffering and loss? The man who in every way incites forcible revolution is responsible when revolution begins, and if he be a courageous man he does not shrink from the consequences. Those who resisted the operation of the Fugitive Slave Law, and sought to save the innocent slave from torture and unspeakable wrong, counted the cost and endured the penalty, whether of the law or of public opinion. Anarchists who justify and counsel murder as necessary to the overthrow of society, when murder begins in consequence of their incitement, cannot be held guiltless. Debating the Documents | The Haymarket Square Riot Second Group of Documents DOCUMENT 2 Written Primary Source Document 2 Information on Document 2 These passages are from an editorial written by Michael Schwab, who was one of those convicted of inciting the Haymarket bombing. The editorial appeared in the Arbeiter-Zeitung on May 4, 1886, the day of that bombing. However, it was written in response to the riot at the McCormick factory the day before. It was written in deep anger about the police actions in that riot. Yet it offers views that were often expressed by the anarchists, including their views on the use of violence by the workers. The editorial was entered as People’s Exhibit 73 at the trial of the Haymarket anarchists. • Document 2 • Blood has flowed. It happened as it had to. Order has not drilled and disciplined her murdering hounds in vain. The militia has not been drilled in street fighting for mere sport. The robbers who know best themselves what a mean rabble they are, who keep up their mammon by rendering the masses wretched, who make the slow murdering of laboring men’s families their vocation, they are the last to be afraid of directly butchering the laboring men. Down with the rabble is their watchword. Is it not an historical fact, that private property has had its origin in acts of violence of all sorts? And shall the “rabble,” the laboring men, allow this capitalistic pack of robbers to carry on through hired assassins their bloody orgies? Nevermore! The war of classes has come. In front of McCormick’s factory workmen were shot down yesterday whose blood cries for vengeance. Who will any longer deny that the ruling tigers are thirsting for the workman’s blood? Countless victims have been slaughtered upon the altars of the golden calf amidst the triumphant shouts of the capitalistic band of robbers. One has only to think of Cleveland, New York, Brooklyn, East St. Louis, Fort Worth, Chicago, and countless other places in order to recognize the tactic of the extortioners. It is “Terror to our working cattle”. But the laborers are not sheep, and the white terror will be answered with the red. Do you know what that means? Very well, you will find that out yet. Modesty is a vice of the workingmen, and can there be anything more modest than this eight hour demand? Peaceably the workmen made it already a year ago, in order not to neglect to give the extortioner opportunity to prepare for it; and the answer to this was: to drill the police force and the militia, and to browbeat the laborers who worked in favor of the eight hour system. And yesterday blood flowed. This is the manner in which these devils reply to a modest petition of their slaves! Death rather than a life of wretchedness! If workmen must be shot at, well then, let us answer them in a manner which the robbers will not soon forget again. The murderous capitalistic beasts have become drunk with the smoking blood of laborers. The tiger lies ready for the jump; his eyes sparkle eager for murder; impatiently he whips his tail, and the sinews of his clutches are drawn tight. Self defense causes the cry “To arms!” “To arms!” If you do not defend yourselves you will be torn in pieces and ground by the animal’s teeth. The new yoke which awaits you in case of cowardly retreat is heavier still and harder than the severe yoke of slavery as it exists now. The Haymarket Square Riot | Debating the Documents 17 Study the Document SECOND group of documents Study the Document: Written Source 1 Instructions: Take notes on these questions. Use your notes to discuss the documents and answer the DBQ. 1 Main Idea or Topic What main point does this editorial make about the guilt or innocence of the Haymarket anarchists? 2 Author, Audience, Purpose From the document and the information on it, who do you think the audience for this editorial was? What purpose do you think the editorial hoped to achieve? 3 Bias What two or three sentences or phrases in the editorial best express its view of the anarchists? What two or three sentences or phrases express its view of ordinary workers? 4 What Else Can You Infer? What is suggested or implied by this document? For example, what can you infer from it about overall business-labor relations at this time? What can you infer about the views of those who supported the Haymarket defenders? 18 Debating the Documents | The Haymarket Square Riot Study the Document SECOND group of documents Study the Document: Written Source 2 Instructions: Take notes on these questions. Use your notes to discuss the documents and answer the DBQ. 1 Main Idea or Topic What overall point about relations between business owners and workers does this document make? 2 Author, Audience, Purpose Read the information provided with this document. How does it help you better understand the point of the document and the tone of its author? 3 Context To better understand this document, what would a reader need to know about labor and industry in late nineteenth-century America? What would they need to know about socialist and anarchist ideas? 4 Bias The document seems to defend the idea of workers using force and violence in their struggles. What case does it make for this? Do you think the case is sound? Why or why not? 5 Usefulness This document was used to convict the Haymarket anarchists. Was this fair? Why or why not? Could a historian use this document fairly? If so, in what way could this be a useful historical document? The Haymarket Square Riot | Debating the Documents 19 Comparing the DOCUMENTS Comparing the Documents The Written Sources Answer the question by checking one box below. Then complete the statements on the Comparison Essay worksheet. Use all your notes to help you take part in an all-class debate about these documents—and to answer the final DBQ for the lesson. Which of these two primary source documents would be most useful to a historian trying to understand the Haymarket riot? Passages from an Passages from an editorial in Harper’s Weekly editorial in the on October 1, 1887, Arbeiter-Zeitung, praising the state court May 4, 1886, written for upholding the by Michael Schwab, a convictions of the defendant convicted in Haymarket anarchists. the Haymarket bombing. Document 1 20 Debating the Documents | The Haymarket Square Riot Document 2 Comparing the DOCUMENTS Comparison Essay I chose Document ______ because: _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ I did not choose Document ______. However, a historian still might use the document in the following way: _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ KEEP THIS IN MIND: Some sources are very biased. A biased source is one that shows you only one side of an issue. That is, it takes a clear stand or expresses a very strong opinion about something. A biased source may be one-sided, but it can still help you to understand its time period. For example, a biased editorial cartoon may show how people felt about an issue at the time. The usefulness of a source depends most of all on what questions you ask about that time in the past. The Haymarket Square Riot | Debating the Documents 21 Document-Based QUESTION Document-Based Question Your task is to answer a document-based question (DBQ) on the Haymarket Square riot. In a DBQ, you use your analysis of primary source documents and your knowledge of history to write a brief essay answering the question. Using all four documents, answer this question. Document-Based Question The Haymarket anarchists often discussed the use of violence for political purposes. Even if they were innocent of the Haymarket bombing, were their critics right to see them as a danger to Chicago and the nation? Why or why not? Below is a checklist of key suggestions for writing a DBQ essay. Next to each item, jot down a few notes to guide you in writing the DBQ. Use extra sheets to write a four- or five-paragraph essay. Introductory Paragraph Does the paragraph clarify the DBQ itself? Does it present a clear thesis, or overall answer, to that DBQ? The Internal Paragraphs — 1 Are these paragraphs organized around main points with details supporting those main ideas? Do all these main ideas support the thesis in the introductory paragraph? The Internal Paragraphs — 2 Are all of your main ideas and key points linked in a logical way? That is, does each idea follow clearly from those that went before? Does it add something new and helpful in clarifying your thesis? Use of Primary Source Documents Are they simply mentioned in a “laundry list” fashion? Or are they used thoughtfully to support main ideas and the thesis? Concluding Paragraph Does it restate the DBQ and thesis in a way that sums up the main ideas without repeating old information or going into new details? 22 Debating the Documents | The Haymarket Square Riot