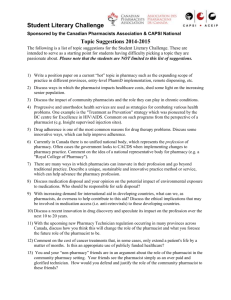

Autumn Symposium, November 2009

advertisement