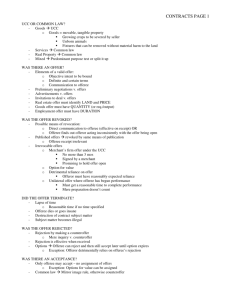

concise contracts - Casey Frank

advertisement