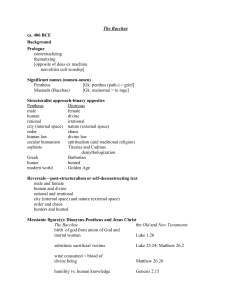

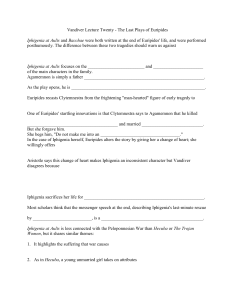

«Dionysian religion: A study of the Worship of Dionysus in Ancient

advertisement