Pre-course materials Classics

advertisement

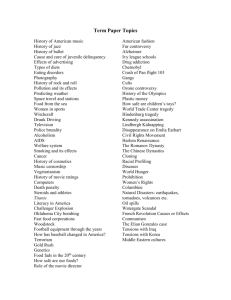

Pre-course materials for A Level Classics Task: What was the purpose of Tragedy in 5th century Athens? ‘Plot is the first principle, the most important feature of tragedy.’ Aristotle, Poetics ‘Greek Tragedy is nothing more than death and violence’ OCR AS Classics May 2012 Structure these answers in paragraphs: How did Greek Tragedy develop in 5th century Athens and what was its purpose? What was the nature of Athenian democracy and what key events took place during its lifetime in the 5th century BC? Do you think the second quote above is justified? Support this with examples and evidence from the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides. What did Aristotle mean be catharsis as a product of watching tragedy? How important do you think the cathartic experience of viewing tragedy was in producing a citizen body that was equipped to function as a democracy? Explain your point of view. Support this with dramatic and historical examples if you can. Can you summarise the evidence that you have presented to give a conclusion? Is Carter correct that tragedy is primarily about politics or is its function one of morality via the plot as Aristotle would suggest? Completion of work: Please title the work AS Classics pre-course materials. Add a date and the label “Independent research” Answer the questions as an extended piece of writing using paragraphs rather than numbered responses. Highlight any words that you use but do not fully understand. (If you can print off these instructions highlight words in the task that you do not fully understand). Check your final piece against the criteria above to ensure you have added sufficient detail. Read over your final draft to check for errors and to make sure your writing is clear and to the point. Please indicate where you find references or key text by adding a bracketed number after a quote or section of research. EG, (1). At the bottom of your page identify where each reference has come from. EG, (1) Plato “Euthyphro Dilemma” Submission is compulsory for all teachers and will form the content of your first lesson in this subject so bring it in on day one of your 6th form career. Pre-course materials September 2015 In your first lesson: This piece of work will be used to form a debate on whether tragedy and morality are dependent upon one another. You will already have examples, sources and case studies to support an opinion. We will use what you have understood to host a silent debate. Suggested reading/viewing: BBC Ancient Greece The Greatest Show on Earth 1of3 Democrats https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xf9cDKqwhQw BBC Ancient Greece The Greatest Show on Earth 2of3 Kings https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EaRIZIPAL6M BBC Ancient Greece The Greatest Show on Earth 3of3 Romans https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tnqz1zxGDTA The Politics Of Greek Tragedy Carter, D.M. 2008 University of Exeter Press An Introduction to Greek Theatre https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aSRLK7SogvE An Introduction to Greek Tragedy https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dSr6mP-zxUc Aeschylus The Persians https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v03XFs9_GUU The birth of tragedy: http://www.sparknotes.com/philosophy/birthoftragedy/summary.html Aristotle on Tragedy: http://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature/a/agamemnon-the-choephoriand-the-eumenides/critical-essay/aristotle-on-tragedy Aeschlyus Agamemnon: http://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature/a/agamemnon-thechoephori-and-the-eumenides/play-summary Sophocles Antigone: http://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature/o/the-oedipustrilogy/character-analysis/antigone Euripides Medea: http://www.shmoop.com/medea/summary.html https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OdtDeZZ4RPk BBC learning zone Medea https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l5-M6OBvAdE The Greek polis and tragedy. “Tragedy, then, is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude; in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament, the several kinds being found in separate parts of the play; in the form of action, not of narrative; with incidents arousing pity and fear, wherewith to accomplish its katharsis of such emotions. . . . Every Tragedy, therefore, must have six parts, which parts determine its quality—namely, Plot, Characters, Diction, Thought, Spectacle, Melody.” Aristotle, Poetics In the 5th century BC, Athens developed the world’s first democracy. This was not a democracy in our own sense but it did require the full participation (sometimes forcibly) of its male citizen body. Following the 1870 Reform Bill which extended the franchise (vote) to many working class men in Britain, the chancellor, Robert Lowe, is purported to have said ‘now we must educate our masters’. Lowe recognized that in order for a democracy to function efficiently, then its voters must be educated and prepared for the decisions that they would be entitled to vote on. This is not dissimilar to ancient Greece. Carter claims that Greek tragedy was not about simple story telling but instead it performed a key political function within the world’s first functioning democracy. Modern scholarship on the issue or importance of politics in tragedy together gives a good Pre-course materials September 2015 illustration of the importance and difficulty of the topic as a whole. A.J. Podlecki's historicist approach relates Aeschylean tragedy to contemporary events and personages. C.W. Macleod prefers to interpret Aeschylus in terms of ancient Greek values: honour (timē) and justice (dikē). S. Goldhill considers the plays against the festive background of first performance, concluding that they ask pertinent questions of democratic values whilst Richard Seaford, believes that tragedy characteristically re-enacts the demise of tyrants in sixth-century Greece and demonstrates a benefit for the city through the establishment of hero-cult. Mark Griffith on the other hand has underlined the importance of royal/heroic families to the storylines of Greek tragedy. Carter suggests that frequently tragedy is political in the stronger sense. This he understands in such a way that 'tragedy could engage with contemporary issues...; and the festival...can be considered as a political organ, allowing the audience to reflect on issues and problems relevant to city life'. Acknowledging the entertaining function of tragic drama Carter underscores his view that 'most (not all) tragedies have some political function alongside the poetic one', the specific criterion being the dramatisation of the interaction between citizens, or of citizens with the wider community, with political authority, and with the law, the presentation of the role of cities, in its protecting role towards its citizens or in its dealing with enemies and other foreigners. Anthony Podlecki's ‘The Political Background of Aeschylean Tragedy’ from 1966, which has been labelled as the historicist approach, is sometimes judged by scholars such as Carter, as too much occupied with precise historical allusions to contemporary events, although he is also sensitive to broader issues and political ideas. In Carter's opinion, the biographical tendency to hear the opinion of the dramatist should make way to an audience-based approach perceiving the many voices heard in this drama. Political tragedy should be understood as a wider field than political action, a concern with general issues as the position of women and slaves, or 'how to run a city, how to be a citizen'. C. W. Macleod's article 'Politics in the Oresteia' (1982) focuses attention on the historical context of the drama; an approach which is opposed to Podlecki's: while Podlecki is eager to look for topical references Macleod is intent on denying them. Macleod's definition of the political in tragedy as 'a concern with human beings as part of a community' (e.g. the Eumenides is concerned with dikê and timê, is applauded by Carter although he considers it too wide, suggesting that one should distinguish between social and political issues. For example, Carter thinks that Macleod's interpretation of the Oresteia as a demonstration of the lack of respect for the institutions of marriage, the household, kingship and generalship agrees with Macleod's definition, but he is in doubt whether all this should be defined as political concerns'. Simon Goldhill's influential article of 1987 on the Great Dionysia suggests that tragedy 'problematises' the polis. However he finds serious weaknesses in Goldhill's argument that these ceremonies should demonstrate the democratic nature of tragic drama, on the basis of the civic ceremonies previous to the performances; there is nothing distinctively democratic in the ceremonies except the libations poured by the ten generals and only few dramas represent Athens as a democracy. In addition most of the ceremonies express general Greek values. In Carter's opinion it is Athens that puts itself on display to a wider Hellenic audience. This point of view has been anticipated by Henk Versnel in an article countering several claims about the democratic nature of tragedy: Versnel argues that Athens, far from Pre-course materials September 2015 manifesting its democracy, demonstrated its imperial position in the Great Dionysiac festival. Carter’s approach to understanding the political nature and purpose of a tragedy falls on three key questions: 1. When was this play first performed? 2. What is the political environment of the play? 3. What is the political identity of the chorus members? In order to understand the political message of the tragedy, these three questions must be answered first. Euripides Medea challenges the citizen audience to consider the proposed rules regarding the inheritance of full citizenship by their sons if their wife is a metic (foreigner); Euripides also challenged the Athenians via Trojan Women when the consequences of the sack of Melos in 415 BC were brought home to those whose votes had led to terrible violence. Tragedy reworks many old stories. Some would argue that its primary purpose was to provide a moral tale for the audience to reflect on. However, many classicists today point to the central role of theatre (including comedy) to Athenian democracy. Watch the Michael Scott programmes on the development of theatre and then read the summaries of the plays that you will study this year to find examples of politics, morality and entertainment. References D.M. Carter, The Politics of Greek Tragedy. Greece and Rome Live. Exeter: Bristol Phoenix Press, 2007. Pp. xii, 209. ISBN 978-1-904675-16-7. Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2008.12.06 Pre-course materials September 2015