Magical Girl Anime - figal

advertisement

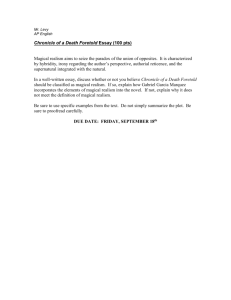

The Journal of Asian Studies Vol. 73, No. 1 (February) 2014: 143–164. © The Association for Asian Studies, Inc., 2013 doi:10.1017/S0021911813001708 Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis: Magical Girl Anime and the Challenges of Changing Gender Identities in Japanese Society KUMIKO SAITO The magical girl, a popular genre of Japanese television animation, has provided female ideals for young girls since the 1960s. Three waves in the genre history are outlined, with a focus on how female hero figures reflect the shifting ideas of gender roles in society. It is argued that the genre developed in close connection to the culture of shōjo (female adolescence) as an antithesis to adulthood, in which women are expected to undertake domestic duties. The paper then incorporates contexts for male-oriented fan culture of shōjo and anime aesthetics that emerged in the 1980s. The recent tendencies for gender bending and genre crossing raise critical questions about the spread of the magical girl trope as cute power. It is concluded that the magical girl genre encompasses contesting values of gender, and thus the genre’s empowerment fantasy has developed symbiotically with traditional gender norms in society. I MAGES OF JAPANESE WOMEN have drastically changed during the global spread of Japanese media since World War II, from subservient wives and geishas in kimonos to a large variety of female characters emerging from the increasingly accessible market of Japanese popular culture where innovative technology and fetish visual culture intersect. Today, the prominence of fighting female characters, most visible in the relatively unrealistic side of Japanese media culture, such as anime, manga, and video games, generates a new stereotype of Japanese women—although they are “Japanese” only so far as their putative origin is Japan. The difficulty of approaching these new venues of popular culture lies in their art of “misrepresentation,” that is, flat and exaggerated visual styles, fantastic storylines, and, most importantly, their general disjunction from real-life women in Japanese society. Whereas interpretive links between female characters and women, well established in feminist studies of film and literature, remain essential resources for understanding functions of gender in text, this new phase of pop culture challenges established scholarly approaches to studies of the relationship between media and society. One of the most striking gaps between Japanese women and female characters in Japanese popular visuals can be observed in how the underrepresentation of “real” women, as reported in statistics and confirmed by common stereotypes, is contrasted to visual representations where empowered female heroes effortlessly surpass men in Kumiko Saito (kumikos@bgsu.edu) is Adjunct Faculty of Japanese at Bowling Green State University. 144 Kumiko Saito physical power and social status.1 One of the key elements that largely helped spread these contradictory images of Japanese culture is the “magical girl,” a well-established genre that has grown and birthed offshoots in its half-century-long history in Japan’s television market. Magical girl animation, called mahō shōjo and majokko anime in Japan, is a mainstay of television animation programming that distinctly targets female prepubescent viewers. The conventions of the magical girl genre, especially the elaborate description of metamorphosis that enables an ordinary girl to turn into a supergirl, have been widely imitated across various genres and media categories. The success of Sailor Moon in the North American market triggered the first wave of cute female-hero action programs, such as Powerpuff Girls (1998–2005) and Totally Spies (2001–present), in the United States and Europe (Loos 2000, 1–2). The ages, genders, and nationalities of anime viewers have increasingly diversified to the degree that one cannot infer types of audience from the content of anime. The basic definition of the genre, however, has remained mostly unchanged. While Western concepts of “genre” may entice people to define the magical girl based on plots and settings, the most practical way to identify this category is primarily by means of its business structure. Many of Japan’s anime programs for children are founded on toy marketing that capitalizes on gender-divided sales of character merchandise and gadgets used by characters in television programs. Unlike the United States and some European countries, where advertising directed at children is seen as highly problematic, it is best to consider Japanese magical girl anime as twenty-five-minute advertisements for toy merchandise. Japan’s outdated production system of animation necessitates approximately a $10,000 deficit out of a $100,000 budget per episode, and the financial gap is barely turned into profit through sales of copyrighted goods (Tada 2002, 81). Some of the most notable examples are the alliance of Bandai and Sunrise Studio’s Gundam series (1979–present) as well as Bandai’s investment in magical girl anime, such as the Sailor Moon series (Bishōjo senshi Sērāmūn, 1992–97) and the Precure series (Purikyua, 2004–present). The magical girl genre’s backbone consists of the marketing strategy to exploit viewer interest specific to a certain gender and age group, mainly girls between four and nine, judging from the targeted ages of the magical girl toy merchandise. The careful exploitation of feminine and masculine ideals in children’s television programs has established gender as perhaps the most powerful and conspicuous ideological tool 1 The 2009 Gender Gap Index shows Japan ranked only 101st among 134 countries in the level of women’s empowerment, juxtaposed by Senegal and Malaysia, while other industrial nations rank at the top (Hausmann, Tyson, and Zahidi 2009). Japanese women’s labor participation and political representation have been exceptionally low in the global scale for a country that far exceeds the average in the level of women’s education and health care (Chiavacci 2005; Inglehart and Norris 2003). Despite an equal-employment law passed in 1986, many Japanese companies continue with separate gender tracks for men and women that presume female workers’ retirement at the time of marriage or first pregnancy. Working and educated women tend to delay marriage, while many mothers continue to regard their employment as a threat to childrearing (Amano 1997; Holloway et al. 2006; Nomaguchi 2006; K. Suzuki 1996). Whereas women’s participation rate in labor has gradually increased, this seeming success is mostly attributed to the growing trend of women delaying marriage and childbearing (Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training 2007; Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2009). Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis 145 that defines and classifies media culture for children (M. Saito 1998, 10). Despite its seemingly unoriginal and repetitive story lines typical of television programs for children, the magical girl genre has been an active site of contesting ideas surrounding gender roles and identities. In public discourse, the general definition of the magical girl anime tends to solely focus on the content. Largely influenced by Tōei Studio productions in the 1960s and 1970s, mahō shōjo as a genre signifies (usually serial television) anime programs in which a nine- to fourteen-year-old ordinary girl accidentally acquires supernatural power; majokko suggests the alternative setting that the female protagonist’s superhuman power derives from her pedigree as a princess of a magical kingdom or a similar scenario. In either pattern, the plot often revolves around the way she wields her power to save people from a threat while maintaining her secret identity. She frequently uses magical empowerment gadgets, such as wands and accessories (to be sold as toys), often accompanied by little animal pets (to be sold as toys). Despite its firm visibility and popularity in Japanese society, the magical girl has been mostly neglected. The existing few scholarly works can be divided between two basic theoretical applications: feminist politics and emergent studies of fan culture. In feminist studies, female characters are often regarded as reflections or ideal models of actual women. This interpretive link invites the argument that strong female characters in anime evidence women’s empowerment in recent Japanese society. Susan Napier (2005, 33) argues, for example, that “[p]opular youth-oriented anime series such as the 1980s Cutey Honey and the 1990s Sailor Moon show images of powerful young women (albeit highly sexualized in the case of Cutey Honey) that anticipate genuine, although small, changes in women’s empowerment over the last two decades and certainly suggest alternatives to the notion of Japanese women as passive and domesticated.” Kotani Mari (2006, 165–69) examines Revolutionary Girl Utena (1997) as a recent example of girls’ anime that possibly subverts gender norms and conventional sexual politics for women. These arguments tend to identify transformation, a common device that changes the female protagonist from a mediocre girl to a cute warrior, as an identity transcendence that undermines fixed traditional gender roles. Although these are attractive claims, the major problem of the premise lies in how difficult it is to hypothesize such reflexive connections between women’s gender roles and the popularity of fighting female heroes. Some scholars question whether the magical girls are really empowered. Napier repeatedly insists on the empowering effect of Cutey Honey’s transformation, yet finally concludes that the eroticism and nudity emphasized in the transformation of Cutey Honey “sends mixed messages” (Napier 2005, 75). A more critical analysis is presented in Anne Allison’s discussion of Sailor Moon, in which she defines the battle heroine as “a self-indulgent pursuer of fantasies and dreams through consumption of merchandise” (Allison 2006, 130). While male superheroes, like the Power Rangers, transform to change their body into a weapon to serve a higher goal, “the process [of a girl hero’s transformation] is more a ‘makeover’ than a ‘power-up’” (138). From a Japanese feminist perspective, Saito Minako (1998, 41) points out that children’s television programs reinforce fixed gender roles functioning in actual society, thereby teaching girls to become a good daughter at home and a good 146 Kumiko Saito OL2 at work. She argues that the female protagonist in the magical girl genre reconfirms the values of femininity, which teaches girls to envision marriage and domestic life as a desirable goal once they have passed the adolescent stage. Compared to female heroes who are cute juvenile girls, Saito continues, women in the enemy force, whether in magical girl programs or the Power Rangers series, are adult women wearing heavy makeup and obsessed with careerism: they are, simply put, the women who failed to be a wife or a mother. According to these arguments, the seemingly empowered girl heroes in anime covertly teach girls to pursue fashion, romance, and consumption until marriage and, once married, to stay at home as a good wife and mother. A contrasting strand of theories stems from a few cutting-edge pop culture criticisms that deal with fan viewers in Japan known as otaku. Otaku is a term that originated in the early 1980s wave of subcultures that marked a new type of fan consumers. These fans actively seek comprehensive knowledge and often have erotic fantasies about visual and textual products, thereby differentiating themselves from “normal” consumers. Saito Tamaki (2000, 258–59) proposes the idea that anime and manga are produced and consumed within an imagined autonomous world of representations detached from what we generally recognize as reality. Accordingly, the abundance of eroticism and violence in anime, for example, does not necessarily result from a projection of consumers’ (or producers’) desire, but rather from representations of sexuality created and consumed in their own self-enclosed economy of desire. Saito further suggests that sexuality in anime, disengaged from sexual desire in reality, helps constitute the sense of reality in the fantastic text. In a similar milieu, Azuma Hiroki (2007, 184) argues that, unlike old-fashioned viewing practices in which viewers find meanings in stories and characters, otaku fans rearrange elements of story and character into fragmented data at surface-level small narratives. This model also assumes that the self-propelled network of representations is detached from objects of representation: that is, flat cuties in visual text produce a system of desire independent of the desire for women in three-dimensional reality. These approaches suggest that the current form of fandom surrounding anime-style female characters necessitates the consumers’ indifference or unresponsiveness to reality. It is further possible that unoriginal fetish cute girls are endlessly produced and consumed so as to sustain the ideological wall between “real life” and the utopia of character fetishism. The two theoretical frameworks above clearly collide in one respect. On the one hand, feminist theories commonly examine how visual text embodies (or disembodies) women, with emphasis on how children learn gender roles in Japanese society. On the other hand, fan culture theories primarily examine adult male fan activity that endorses the alienating effect between representation and reality. This essay adds a historical perspective based on simple and orthodox academic principles that state that a genre or concept forms through complicated historical processes and individual texts. The advent of the magical girl genre in the 1960s neatly overlaps with the history of television in Japan. Countless television series have been released since television became a standard in home electronics, yet the aforementioned two frameworks respectively cover a limited range of viewership and textual examples. A historical look at the genre presents 2 “OL” is a Japanese word that stands for “office lady,” which refers to female office workers off the career track whose tasks often include serving tea and making photocopies. Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis 147 a new facet to discrepancies between the two theories. The following discussion is divided into three eras corresponding to the periodization of the genre’s development, which are the 1960s–70s (Showa 40s), the 1980s (50s to the end of Showa), and the 1990s to the present (Heisei era). This layering of the genre history corresponds to the vicissitude of the entire anime industry identified by the same three waves (Tsugata 2004, 151–52). Introducing a historical perspective alone, however, fails to explain the current condition of the magical girl industry. The dual context of magical girl anime, as children’s programs that convey messages about gender roles reflecting standardized social norms and as a stand-alone vortex of representations operated by visual fetishism of young female bodies, may respectively belong to the two different eras of the 1960s to the 1980s, but today the genre has grown to easily incorporate both contexts and beyond. In fact, Tōei’s contemporary magical girl productions target both girls between four and nine years old and men between nineteen and thirty years old.3 As the anime market itself adopts new technologies for distributing moving images to potential customers in niche markets, the visual text’s messages are becoming increasingly ambivalent. Representations of magical girls today present contradictory messages and thereby serve to mend various fissures of values in society. This paradoxical function of the genre should not be confused with the polysemic reception of the text by viewers. The magical girl as a genre consciously takes advantage of the oxymoronic rhetoric of “magic,” a semantic tool that provides different, often opposite, meanings about women’s duties, power, and sexuality. It is not an exaggeration to say that the genre’s progress corresponds to the development of the visual and narrative rhetoric that skillfully encompasses the conservative agenda of the genre. In this essay, I will argue that the complicit relationship of opposing messages serves as a functional gear of the larger social mechanism that generates and reconfirms conventional gender norms and heterosexuality. GENDERED ROLE MODELS FOR GIRLS: 1960S–70S TŌEI PRODUCTIONS Japan’s first television animation programs known as “TV manga” appeared in 1962– 63 and were followed by the rushed release of more than ten animation programs per year, but none featured a female protagonist until the late 1960s. Tōei Studio, which extended its range of production to children’s animation while its primary business in the film industry stagnated due to the rise of television, produced the first heroine anime, which essentially became the first magical girl anime, Sally the Witch (Mahōtsukai Sarı̄, 1966–68), soon followed by Secret Akko-chan (Himitsu no Akko-chan, 1969–70). Both stories were written by two of the most popular writers of boys’ manga in the day, respectively Yokoyama Mitsuteru and Akatsuka Fujio. Without any actual precursor, the major elements in settings and characters were borrowed from live-action television programs that were already proven successful among a young female audience, especially the American situation comedy Bewitched (1964–72). 3 The information was taken from the advertising posters of the first Precure series published in 2004. While Tōei does not publicly announce the main viewer targets of the Precure series, it holds events for young viewers and adult fans separately by setting age limits for admission. 148 Kumiko Saito The 1960s “witch” housewife theme waned quickly in the United States, but various cultural symbolisms of magic smoothly translated into the Japanese climate, leading to Japan’s four-decade-long obsession with the magical girl. Bewitched incorporated the concept of magic as female power to be renounced after marriage, thereby providing “a discursive site in which feminism (as female power) and femininity has been negotiated” (Moseley 2002, 403) in the dawning of America’s feminist era. Japan’s magical girls represented a similar impasse of fitting into female domesticity, continued to fascinate Japanese society, and came to define the magical girl genre. In direct contrast to the American heroines Samantha and Jeannie, however, whose strife arose from the antagonism between magic (as power) and the traditional gender role as wife or fiancée, the magical girl’s dilemma usually lies between female adulthood and the juvenile female stage prior to marriage, called shōjo. In other words, the magical girl narratives often revolve around the magical freedom of adolescence prior to the gendered stage of marriage and motherhood, suggesting the difficulty of imagining elements of power and defiance beyond the point of marriage. In fact, these programs were broadcast exactly when the rate of love-based marriage started to surpass that of miai (arranged marriage),4 which implies that the magical girl anime, founded on the strict ideological division between shōjo and wife/mother, may have been an anxious reaction to the emergent phase of romance. The two classics of the genre, Sally and Akko-chan, embody many of the social expectations for women in Japan’s era of high economic growth. Yumeno Sally is originally a crown princess of a magic kingdom, who descends to the human world when she is deeply fascinated by human girls of her age. In order to become the queen of the magic kingdom, she must stay in the magic world, but as a young, active girl, she chooses to explore friendship with her classmates and learn various customs and social codes in the human society. Her stay in an ordinary suburban Japanese community is approved under the condition that she returns to the kingdom if her identity is revealed. The most notable themes in the program are the humanizing process of Sally, an alien to the human world, and her learning of the limits residing in the power of magic. Throughout the series, moral messages predominate, which can range from the question of humanism beyond the reach of magic to good manners, justice, willingness to help others, and friendship. Most episodes are fringed with the presence of Sally’s father, who seems to persistently observe his daughter’s behavior through a magic mirror, often censoring Sally’s interactions with boys. The relationship between Sally and her parents faithfully reflects a traditional patriarchal family model consisting of an authoritarian father whose values are the law, a gentle mother who obeys her husband’s orders yet secretly helps her daughter, and a daughter who learns to become a good daughter by realizing her father’s wishes and imitating her mother (M. Saito 1998, 41). Even though the ability to control physical law and human mind clearly indicates a form of empowerment, the symbolic function of magic leads in the opposite direction. Sally’s freedom exists in the human world where magic is denied, or at least proven useless for truly human goals (say, moral learning and enlightenment), whereas the 4 According to the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (2010), the inversion process occurred between 1965 and 1969, with approximately 45 percent arranged marriages and 49 percent love-based marriages. Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis 149 magical world represents the patriarchal home to which she must return after an interim period of freedom in the human community. Sally’s life resembles a moratorium, a postponement of taking up her domestic duties as a married woman in the magical kingdom. The final episode highlights this underlying theme by stressing Sally’s desire to stay in the human world against her devoir to enter the market of marriage. Forced to return home, Sally appeals for an extension of her stay, which is granted under the condition that she exceeds her male rival in the final exams at school. Sally loses the academic game against the boy, soon followed by incidents that force her to reveal her identity and return home. Sally’s predicament mirrors familiar conditions of schoolgirls in the prewar era, which is known as the culture of shōjo. About the rush to found girls’ magazines around 1910, Hiromi Tsuchiya Dollase (2003, 727) points out that this new term and concept “shōjo” referred to “the mental state to which girls of this age are prone which makes them want to temporarily take leave of reality and becoming other than what they are.” The fantasy world of the magical girl creates an escapist world where girly daydreaming is turned into a narrative of power, not unlike stories by Yoshiya Nobuko (1896–1973), who created the world of shōjo with “flowery language and the sentimental narrative tone” (Dollase 2003, 728). This early magical girl series inherits the classical dilemma of shōjo, whose creative escapism in adolescent same-sex fantasy also works as a form of resistance to patriarchal society and compulsory heterosexuality (M. Suzuki 2006, 582–83). The irony of magic for this first magical girl is the duality of magical power: she has the freedom to resist patriarchal society through magical empowerment only so far as the same magic forces her to quit the adolescent stage and reclaim her biological heritage as a princess, a wife, and a mother. The symbolic implication of empowerment and resistance in the magical girl setting paradoxically reaffirms the existing system of marriage and home-making through adjournment of gender imposition. Akko-chan altered many components of the setting and gadgets employed in Sally, yet sustained the gendered symbolisms of magic. It dismissed Sally’s unrealistic setting that the heroine is a crown princess of the magic kingdom, instead centering the story on an ordinary Japanese girl without any supernatural power endowed by birth. She gains the magical power when the spirit of her mirror appears and awards her a magical compact mirror that enables transformation. She uses transformation to help her community members, such as saving friends from bullies and helping to solve domestic problems. The compact mirror modeled as toy merchandise became an impetus for the marketing method of later magical girl titles. Whereas Sally presented slapstick mishaps caused by a Caucasian-looking alien princess in her struggle to settle in a Japanese community, Akko-chan not only employed Japanese settings in the heroine’s character and appearance, but also added presumably traditional Japanese tastes of melodrama by adapting ideas and plots from postwar culture of hahamono (mother genre). Hahamono is generally understood as a film genre of cheesy melodrama that thematizes hardship and self-sacrifice of a mother fated to adversities. This genre peaked in the chaotic postwar environment of the early 1950s, when the maternal legitimacy among different mothers (biological, foster, and in-law) and the decline of the paternal authority were called into question (Minaguchi 2005, 113). Yonezawa (2007, 1:137) observes that many manga writers (mostly males from the Tezuka generation) applied genre conventions of shōjo shōsetsu, which was a modification of hahamono melodrama into girls’ fiction and manga that apotheosizes 150 Kumiko Saito Figure 1. Akko-chan’s transformation using the compact mirror suggests both the freedom of girlhood and the destined path to female adulthood (Tōei Animation 2010). the shōjo figure. Yonezawa further points out that the shōjo-ness of the heroine was represented as visual cues, such as cuteness (kawai-sa) characterized by slim limbs and big, round eyes “like a doll in a picture” (1:137). In this respect, Oshiyama (2007, 87) also argues that the popularity of the hahamono style in early shōjo manga owes much to the visual staging of the girl’s purity and beauty against the backdrop of foredoomed calamity. Akko-chan crystallized these idealisms of shōjo as a quintessence of beautiful girlhood destined to perish soon (see figure 1). The combination of magical empowerment and shōjo-ness framed by the doomed nature of transient girlhood naturally created ambivalent messages in Akko-chan as well. In the societal milieu in which Japan was undergoing the politically turbulent era of Marxist student movements at the largest scale in the postwar era, Akko-chan’s superhuman ability to transform into anyone (or anything) is quite revolutionary, implying a sense of women’s liberation. Despite this potential, her metamorphic ability never threatens gender models, as she typically dreams of becoming a princess, a bride, or a female teacher she respects. The use of magic is also largely limited to humanitarian community services in town. Akko-chan’s symbolic task throughout the series focuses on how to steer her power to serve her friends and family, leading to the final episode in which she relinquishes magic to save her father. Akko-chan embraces the cross-generic mismatch between the radical idea of empowering a girl with superhuman ability and the hahamono sentimentalism idealizing women’s self-sacrifice. All in all, the new setting adopted in this series, that a mediocre girl accidentally gains magic, became a useful mechanism for the underlying theme that the heroine is foredoomed to say farewell to magic in the end. This rhetorical device transforms latent power of the amorphous girl into the reappreciation of traditional gender norms by equating magic with shōjo-hood to be given up at a certain stage. Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis 151 These two programs, as well as many of their successors, adapt ideological models of gender from prewar and postwar periods, a rather conservative approach against the potentially subversive symbolism of magic in the era of the women’s liberation movement. The meaning of magic encompasses contesting ideas of what women can and should do, which are split between the adolescent freedom from social restrictions and the compulsory path leading to female domestic work and community service. The key component of the genre is the transience of life as a magical girl, which endorses the premise that the magical power is condoned as far as it is merely an interim period for enjoying shōjo-ness before undertaking female duties. The almost total absence of the heroine’s serious pursuit of romance or any self-awareness of sexuality further strengthens the idea that being a magical girl is a temporary phase of gender vacuum. These early magical girl programs embody antagonisms between traditional gender expectations and emerging concepts of women’s power. But unlike American counterparts in which power and femininity were negotiated through female adulthood, the magical girl programs strictly relegated contexts of power into the unique status of shōjo stamped with an expiration date, thereby maintaining the traditional meaning of marriage unchanged. NEW SHŌJO CULTURE AND THE 1980S EMERGENCE AESTHETICS OF OF ANIME VIEWING: OTAKU In the 1970s, following the success of Sally and Akko-chan, Tōei continued to produce magical girl anime with partial adjustments and improvements, ranging from melodramatic romance to action comedy, with the heroines using magic, physical strength, or technological extrasensory power, but the genre overall declined steadily. Contrary to Tōei’s relatively ascetic portrayals of girls’ romance and sexuality, however, most successful magical girl anime from the 1970s emerged from test productions inviting a wider range of viewers to this feminine genre, including Mysterious Merumo (Fushigina Merumo, 1971–72), Cutey Honey (Kyūtı̄ Hanı̄, 1973–74), and Meg the Witch (Majokko Megu-chan, 1974–75). Regardless of the content or intent, they all shared in common the almost aggressive visual portrayal of the female body, often laboriously invested in animation of female flesh and its instant metamorphosis into a seductive adult body. Although Susan Napier (2005, 73–74) rightly discusses Cutey Honey as pornographic anime, it is also important to note that Honey and its successors like Meg were originally intended for mostly preteen girls. These three series extrapolated the magical girl genre toward a form of visual pleasure centered on the heroine’s erotic charm and sexual empowerment amplified by the use of magic. The magical girl genre’s downfall in the 1970s was not the sole reason for its shift toward sexually provocative visuals that invite male and older female viewers. Apart from the anime industry, comics for girls, known as shōjo manga, became increasingly popular and original, stimulated by the emergence of new narrative techniques and innovative storylines. Some of these sprouting manga quickly turned into the most popular television animation, including Candy Candy (1976–79), Aim for Ace! (Ēsu o nerae!, 1973–74, 1978–79), and Here Comes Haikara-san (Haikara-san ga tōru, 1978–79). These embodied the first media-crossing outburst of shōjo manga for young women written by young women, through which girls pursued the new “self” within personal 152 Kumiko Saito reflection on sexuality (Miyadai 1993, 38–40) in order to create “‘my culture’ that is timeless and deprived of historicity, dissociated from external restrictive frames such as nation and tradition” (Honda 2004, 168). Many of the 1970s shōjo manga employed this timeless, internal depth of the protagonist’s psyche through gender ambiguities (Oshiyama 2007, 141–42; Yonezawa 2007, 136), which propelled young women’s internalized imagination of personal romance and psychological growth, an element generally lacking in the classic magical girl anime. Tōei stopped its magical girl serial production in 1981 while shifting to other genres, and did not record another success until Sailor Moon in the 1990s. While Tōei withdrew, other studios entered the genre, among which were Ashi Production (Ashi Pro) and Studio Pierrot. Both Ashi Pro and Pierrot had already won acclaim from anime fans due to their original productions, making some writers and animators, including Oshii Mamoru, famous. Their first magical girl productions, namely Ashi Pro’s Minky Momo (1982) and Pierrot’s Creamy Mami (1983), almost entirely changed the context of the magical girl raison d’être. Their innovation in treatment of both style and semantics largely stems from two changes in the genre. First, anime’s value expanded from its promotion of merchandise sales as twenty-five-minute-long toy commercials, toward visual commodities that allegedly have their inherent values in being owned by individual consumers. It is no coincidence that this phase parallels the emergence of VCR technology that enabled personal recording and viewing in the mid-1980s. Second, successful animation studios’ new investments in the magical girl increased male fans’ mobility toward this classic feminine genre. Accordingly, the magical girl genre after this period covers the viewer expectations and visual grammars drawn from malecentered anime that feature robots, battle action, and “fan service.”5 The challenge of reading anime after the 1980s stems from the emergence of fan culture surrounding anime, including fan fiction writing, costume playing, and other grassroots activities that deconstructed the gender = genre formula of children’s media. This contemporary marketing strategy evidences that the male viewership, and possibly the male subjectivity, is deeply wedged into the magical girl genre. These two fan-based factors—the commodification of the anime text and the inclusion of the male gaze—helped to introduce a unique measure to valorize the quality of visual art based on a new aesthetics of limited animation. Japanese limited animation techniques, which are often ascribed to Tezuka Osamu’s cost-cutting technique in the 1960s (Akita 2005, 228), consist of material restrictions, including limiting the number of drawings to eight or fewer per second, using static characters with three-cel animation of the mouth, repeatedly using the same cels in similar actions or situations (called the “bank system” in Japanese), and employing complex camerawork and editing that counterpoise the lack of animated motion, especially fast cutting (228–29). This economical approach led to the general emphasis on the complex plot (233), while befitting the Japanese tendency of imagining the totality of the story based on a limited range or fragments of image and action (Akita 2005, 235–36; Ōtsuka 2001, 105). Itō Gō (2005) argues that the poor quality control of images in Tezuka’s works 5 “Fan service,” a Japanese term that literally means serving fans, signifies shots and scenes in manga and anime that are presented to please the viewer’s (often sexual) interest. Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis 153 corresponds to the spread of the modern narrative in manga and anime, which signifies the supremacy of the internal psyche and the profound story over the image. Material limitations directly helped develop the complexity and depth of narrative, which is the stage to be called anime and manga’s “modernist era.” The 1980s anime fan culture presumably transvalued the limited animation style and generated a new set of aesthetics that critics today tend to call postmodernist. Azuma (2001, 26–27) points out the coincidence between the rise of otaku fandom and the surfacing of postmodernist critics, as exemplified by Asada Akira in 1983. He compares anime’s postmodern condition in the 1980s and 1990s to what Jean-François Lyotard (1984) calls the collapse of the grand narrative. In the era that lost the depth, reality, and universality of the modern grand narrative, Azuma (2001, 50–52) argues, otaku people simply realign information into their database that lacks the center or stratum of meaning. The consumption of the story no longer signifies hermeneutic understanding of the text’s messages: otaku consumers instead regroup data to create secondary fiction, blurring differences between fan fiction and originals. What comes after the death of the story is the character (Azuma 2001, 58; Itō 2005, 88), or “chara” (kyara) in Itō’s term, which is different from “characters” in the sense that charas appear as signs that lack the depth and context that are indispensable for a round human character (Itō 2005, 118). The charas are easily classified into a database of iconic patterns, such as “maid” or “pink hair,” which enables secondary fiction writing to simply reproduce images and settings of charas. Saitō Tamaki (2000, 248) presents a similar argument about otaku fandom, in which fetish characters serve as objects to be owned across different media, ranging from character-printed goods to figurines. This postmodern conversion in the anime market supposedly emerged in the early 1980s and came to define contemporary subcultures surrounding anime and manga. The conventions of the magical girl genre transformed significantly against this paradigm shift. Both Minky Momo and Creamy Mami originally targeted children, recording a decent outcome in business and eventually leading to the revival of the genre. Because the plots are directly built on the genre clichés, however, the jokes and sarcasm of many episodes appear comprehensible only to adult viewers equipped with the knowledge of the Tōei magical girls. The intrigue of these programs largely lies in the way they parody and mock the established genre conventions, especially the restrictive function of magic and the meaning of transformation. The genre is now founded on the expectation that the adult viewer has acquired a diachronic fan perspective to fetishize both the characters and the text’s meanings. Creamy Mami presents the story of fourth-grader Yū, who gains magical power that enables her to turn into a sixteen-year-old girl. Yū’s magical power is more restrictive than Momo’s, for her superhuman capacity simply means metamorphosis into her adult form, who happens to become an idol singer called Mami. Given that the magic’s ability is selforiented cosmetic effect and bodily maturation, the heroine’s ultimate goal by means of magic is to grow old enough to attract her male friend Toshio, who neglects Yū’s latent charm but falls in love with the idol Mami. The series concludes when Yū loses her magic, which correlates to Toshio’s realization that Yū is his real love. Mami’s thematic messages teach the idea that magic does not bring much advantage or power after all, or rather, magic serves as an obstacle for the appreciation of the truly magical period called shōjo. The heroine gains magic to prove, although retroactively, the importance 154 Kumiko Saito of adolescence preceding the possession of “magic” that enables (and forces) female maturation. Some episodes in Minky Momo can be even more disheartening. Whereas it imitates the traditional princess-in-training formula found in Sally, the series also introduces the viewer to the magical girl’s reality in which her magic signifies little more than transforming herself into an eighteen-year-old form of herself with a certain occupational skill. The magical empowerment sometimes reveals the sarcasm of forced maturation, implying that adult society is less exciting than tiresome and disappointing. The original purpose of her stay in the human world was to bring back dreams and hopes to humans, but her efforts to save people in her adult form appear mostly useless compared to the utter impact of her carefree cuteness that makes “us,” the viewers, happy. The series ends when Momo dies in a car accident and is reborn as an ordinary human baby. If the classic magical girl’s dilemma—magic as power and liberation on the one hand, and domestic duties on the other—stemmed from women’s split life across the turning point prior to marriage, these new magical girls reached an extreme by denying magic, that is, female maturity, including romance and sexuality. The magical girls’ true goal becomes the eternal deferral of growth, and their task, to be just cute and young (see figure 2). This anime philosophy goes hand in hand with the commercial culture of childish idols and Hello Kitty-based cute merchandise that rapidly spread in the early 1980s in Japan. This cute trend, which Kinsella (1995, 243) describes as “a kind of rebellion or refusal to cooperate with established social values and realities,” enticed the magical girls as well into the post-industrial practice of indulgence in consumption of cute images. It is in this cultural climate that transformation sequences became a key component of the genre. Because the genre’s message now resides in the reappreciation of shōjohood, feminine sexuality—one of the most attractive elements to adult male viewers— must be expressed in the form of its denial, a foundation of the so-called “Lolicon”6 taste, which locates eroticism in its absence. The metamorphosis scene, as seen in Momo’s transformation and most of the later programs in the genre, employs the “bank system,” which is to repeat the same transformation sequence in each episode. Although the technique of reusing cels in multiple episodes was not a new concept in itself, Momo successfully incorporated the well-exploited robot anime’s bank method in which mechanical parts are captured in the camera’s dynamic tracking motion for the maximum effect of promoting the target merchandise. Fragmentation of an object into shots is one of the most effective ways to show the details of the toy, thereby making it appear attractive to potential buyers, while it can simultaneously redeem the lack of human and material resources. Momo’s transformation conforms to this limited animation technique as it abundantly splices close-ups of limited body parts, leading to the choppy circular tracking of Momo’s nude body in transformation. Despite such poor configuration of space, the screen duration for the transformation sequence tends to be unnaturally long.7 This disintegration of space paired with the expansion of time is a major characteristic of the magical girl transformation sequence that develops 6 “Lolicon” is a Japanese abbreviation for “Lolita Complex,” a taste for visual representations of young girls common in anime and manga. 7 Momo’s transformation is about twenty-three seconds. Sailor Moon’s transformation sequence is about forty seconds (first season), and Precure’s (first season) is more than one minute when uncut. Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis 155 Figure 2. Minky Momo, the first anime character with vivid pink hair whose symbolic task is to be cute (Bandai Visual, n.d.). from Momo to Sailor Moon and more recent ones that openly sell fetishism of the metamorphosing body. The spatial dissection of the female body allows the camera’s gaze to explore the depth of the viewer’s affection in the disembodied body. These technical innovations of transformation go perfectly with the symbolic function of shōjo, that is, the transience that lasts forever. This fantasy is secured by repetitions of transformation sequences, a limited animation technique that repeats the act of border crossing between shōjo and her sexual maturity, thereby enabling viewers to envision the simultaneity of sexuality and its absence. It is important to note that the VCR technology greatly contributed to the emergence of repetitious viewing in the early 1980s, essential 156 Kumiko Saito for anime fandom (Okada 1996, 8). The bank sequence is meant for repetition, and this repetition itself becomes visual pleasure. The thematic feature of the 1980s magical girl, which is to rediscover and reaffirm the innocence of shōjo retroactively, further enhances the value of repetitious viewing, for the recurrence of the bodily transgression between the past and the future protracts the fantasy of the shōjo, whose sexual maturation has already happened and will never happen. GENDER BENDING AND NEW MEANINGS OF POWER: 1990S–2000S FEMALE BATTLE HEROES Toward the late 1980s, the Japanese economy reached previously unseen heights of stock and asset prices, known as a bubble economy, soon followed by the “bubble burst” and a long recession leading to the current global financial crisis. The third phase of the genre concurs with this prolonged period of social anxiety coming from the collapse of Japanese myths, from the corporate management system of lifetime employment to welfare systems stressed by an aging population. Simultaneously, the marriage rate and birth rate dropped to the level that, researchers estimate, 40 percent of the Japanese population will be over sixty-five years old in 2055 (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research 2010). Naturally, children’s media culture reacted to these socioeconomic transitions. The Power Rangers series, for example, which reflected “the new industrial model of postwar Japan,” as represented by Toyotism and Sonyism (Allison 2006, 100), recorded the most radical fall of audience share around 1990, continuing to the series’ period of lowest viewership in 1994–96.8 Some popular manga and anime were clearly digressing from conventional heroic narratives, possibly mirroring crumbling masculine confidence. Especially eminent is the rise of female battle hero narratives, which originally circulated only among fans with an eccentric taste but quickly came to catch public attention in Japan, and soon in the international market, such as Bubblegum Crisis (1987–91), Patlabor (1988), Aim for Top (1988), and Ghost in the Shell (1989–2001). In the meantime, the Friday evening spot long reserved for the Power Rangers series was occupied by Ranma 1/2 (1989–92), an action comedy anime about a martial arts hero who metamorphoses into a cute girl each time he is in contact with cold water. In parallel, the third wave of the magical girl genre emerged as an art of crossreferencing among multiple genres and gender codes. Reacting to withering Power Rangers programs, Tōei branched off a comedic battle heroine series Masked Beauty Powatorin (1989–90), which directly became a model for Sailor Moon, a parody of teamed-force battle hero action. Following the success of Sailor Moon, the magical girl genre revived with various series that played with gender-crossing themes. Lesbian and gay romantic interests are openly addressed in CLAMP’s Cardcaptor Sakura (Kādokyaputā Sakura, 1998–2000), while its other magical girl series Magic Knight Rayearth 8 According to Video Research Ltd. (n.d.), the Power Rangers (Super Sentai) series viewer ratings averaged 10–13 percent until 1988, dropping to 6–7 percent in 1989–93. Between 1994 and 1996, the ratings recorded were the lowest at 4.5–4.8 percent on average. Currently the series regularly maintains 7–8 percent. Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis 157 (1994–95) makes female heroes pilot giant robots to save a princess. In the meantime, magical girl manga and anime solely targeting an adult male audience became increasingly visible, ranging from Pretty Sammy (Mahō shōjo Puriti Samı̄, 1996) to Lyrical Nanoha (Mahō shōjo Ririkaru Nanoha, 2004). Tōei’s most successful magical girl anime, Precure, features action battles planned by the series director of Dragonball. With these genre-crossing diversifications and gender-confusion tendencies, the magical girl from this period is far less a genre than a code that binds certain ideological values and advantages attributed to the shōjo identity in contemporary Japan. Accordingly, the implications of the shōjo altered significantly along with a seemingly minor change in the genre’s stylistic mannerism, that is, metamorphosis. Whereas the magical girl genre prior to the 1990s clearly involved literal transformation of the body, usually from a small girl into an adult woman (that is, sixteen years old or older), recent magical metamorphoses rarely concern actual physical growth. Many of the magical girl anime still utilize the visual euphemism of transformation by adding frills or accentuating a hair style, but their morphing does not go beyond a cosmetic makeover. This trend can be observed in Ashi Production’s magical girls in 1990–92 and ensuing Tōei productions like Sailor Moon. A possible reason for the decline of physical transformation is the 1988 Miyazaki Tsutomu “serial murder of little girls” (renzoku yōjo satsujin jiken) case,9 which became an impetus for the mass media’s scandalization of anime’s pedophilic taste as a potential cause for sexual crime. Whether this was the true cause or not, later makeover magical girls established their own aesthetics within the absence of flesh maturation befitting the changing social condition. In either stage of the 1960s conservatism or the 1980s otaku culture, “growing up” via magic signified some form of empowerment, whether social or sexual, but this symbolic system of visual language seems to have collapsed. In other words, magical girls may no longer need the grow-up magic to claim power—shōjo are already powerful as they are. This “power” is of a highly schizophrenic kind, however. On the one hand, with the erosion of the shōjo-adult boundary, many adult obligations—especially maternal and other domestic roles, as well as financial responsibility for the family—entered the life of the magical girl. From Sailor Moon to Magical Do Re Mi (serialized 1999–2003) and Precure, the virtual experience of maternal duties is a component that consistently intervenes in the battle heroines’ everyday life, ranging from caring for a baby to building a mother-daughter cooperative relationship. In Cardcaptor Sakura’s motherless household, the family members rotate on housework, including fourth-grader Sakura herself cleaning and cooking in many episodes. Sailor Moon’s later series could not succeed without the virtual family relationship of Sailor Moon, her future husband Tuxedo Mask, and their daughter who time-traveled from the future. In Do Re Mi, owning and running a store to earn magical money that fuels their power weighs heavily with the witch-candidate protagonists who aspire to climb the ladder system of witchcraft to the top. Romance, which was a reward after a bittersweet farewell to shōjo-hood, is now the essence of magical girls’ everyday school life. As various duties and pleasures originally reserved for female adulthood penetrate the shōjo stage, their everyday life 9 Miyazaki Tsutomu kidnapped and murdered four girls aged four to seven. The mass media depicted him as a mentally abnormal “otaku” whose pedophilia culminated in capital crimes. 158 Kumiko Saito appears increasingly busy and multitasked, even overstrained from undertaking many responsibilities simultaneously. In this respect, many of today’s magical girl programs continue to provide young girls the opportunities to envision adulthood that fits the demands of the contemporary society. On the other hand, contrary to the above tendency, the attenuation of the shōjo-adult boundary is also bringing about an infinite extension of the shōjo phase. From this perspective, the adult tasks, including childrearing and job training, turn into temporary game play, such as Tamagotchi-like digital pet-raising games and various toys for fulfilling feminine fantasies about accessories, baking, dance, and fashion. Concerning Sailor Moon, for example, Allison (2006, 139) explains that, “[a]ssumed to bear the fewest responsibilities and pressures to be socially productive, the shōjo (as both subject and object) has come to stand as the counterweight to the enterprise society.” The dream identity of shōjo originates from her status as liberated from a wide variety of obligations undertaken by men, as well as from domestic obligations of married women. Whereas enemies are often power-hungry seductresses with thick makeup, the visual and figurative measure of the magical girl’s power is shown by youth and cuteness, such as frilly layers of skirt added to a school uniform (see figure 3). If transformation in the previous era signified empowerment by growth, the 1990s magical girls maximize their power by simply being themselves—cute and carefree students. Accordingly, there is little, if any, realistic connection between power and its wielder in the new magical girl trope, compared with the military or coercive power of male heroes or the classic magical girl’s restrictive magic constituted by her social and communal usefulness. Given that cuteness is a concept associated with youth, passivity, femininity, and, overall, powerlessness, the recent brand of magical girls—cute battle heroes—is a sheer paradox of claiming power in powerlessness. The notion of cute culture as a passive form of resistance is not a new concept, as already discussed earlier. What is new in the current condition is that this culture of feminine and juvenile defiance is widely diffusing into Japanese men’s identity, or possibly, into Japan’s national identity on an international scale. Scholars and journalists have reported that Japan’s brand image is shifting from a feudal past and modern bureaucracy to pop culture driven by the youth-oriented “cool.” In reaction to Douglas McGray’s article on “Japan’s Gross National Cool” in 2002, the idea of Japanese pop culture as a means of cultural diplomacy entered Japan’s mainstream discourses, including Asahi Newspaper, Nikkei Weekly, and Gaiko Forum. The government has utilized this cultural boom to heighten its image, through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ cooperation with the private sector and other overseas diplomatic strategies (Otmazgin 2008, 80). In this process, “the masculinized image of Japan at work . . . has given way to that of feminized Japan at play,” or more precisely, “Japan as play” (Yano 2009, 684). In the domain of the magical girl industry, the feminine image of Japanese pop parallels the emergence of men’s magical girl anime, or genre parodies and spin-offs released only on video or broadcast in midnight spots, apparently separated from the children’s toy market. It is worth noting that those with lasting popularity among fans, especially Pretty Sammy and Lyrical Nanoha, are offshoots from anime or games that typically serve a male fantasy of harem-style heterosexual romance, in which a mediocre boy becomes a love interest of multiple cute girls. Whereas this common type of men’s paradise in anime and games invites (or forces) the male protagonist to simulate romantic, and often sexual, exploration with Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis 159 Figure 3. A clear contrast staged between the enemy queen as a seductive adult woman and Sailor Moon as shōjo (Takeuchi 1993). multiple girls, the magical girl byproducts are almost entirely devoid of romance, sex, and even male figures that can be a threat to shōjo’s pre-pubertal utopia. In contrast to the overwhelming presence (and pressure) of romance in the originals, the spin-off magical world usually consists of female friendship and ordinary but fun school life, which forms a pseudolesbian community in which girls enjoy a carefree everyday life. Simultaneously, it is no longer uncommon to find stories about boys transforming into magical girls, a sort of empowerment desire realized by means of cross-dressing as 160 Kumiko Saito Figure 4. The magical boy as a criticism of the increasing difficulty in envisioning male hero models (Ishida 2007). shōjo.10 Calling this trend “men’s feminization” perhaps misrepresents the situation, however: the magical girl as an epitome of shōjo actually provides viewers the agency for a heroic and independent identity against the failing image of male adulthood. To cite a magical boy manga, the deteriorating image of the paternal role is making it difficult to project a hero model on a male member of one’s family (see figure 4). Although the 10 Some examples that are popular enough to turn into television series are Ubukata Tō’s novel Chevalier (2005–present) and Tsukiji Toshihiko’s novel Kämpfer (2006–present). Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis 161 visual rhetoric of power relies on feminine implements like frills and long hair, it is becoming increasingly difficult to equate representations of the magical girl’s gender with biological sex. The shōjo, whether male or female, now appears like a presence whose transcendence over the childhood/adulthood dichotomy determines her power. The changes we observe today, therefore, do not necessarily derive from the feminization of men, but from a new configuration of gender that wields its power in its youthfulness and cuteness. If the magical girl identity now blankets both genders’ perspectives, then it is possible to assume that the transition to the adult world (especially marriage, sex, and childrearing) is equally considered a crisis by men as well as by women. To cite a magical girl trope from Puella Magi Madoka Magica (Mahō shōjo Madoka Magika, 2011), vastly successful anime among Japanese men today, the magical girl’s true task is to fight against her own adult form called “witch.” As could be seen in the 1980s development of shōjo culture, the Japanese cute values generated from deferrals and refusals to undertake gendered roles expected by the social standards, that is, a passive, temporal, and disguised leeway to play resistance to maledominant adult society. This method proved popular and effective in a country where gender inequality is tightly embedded in the social system. This is a form of resistance only so far as it simultaneously maintains the existing power structure against which the resistance is intended. In a similar way, the magical girl’s power can be considered as power only so far as her entry into the adult world of “real” power is precluded. The growing appeal of the genre to adult men may equally signify men’s resistance to their gendered responsibilities, such as deferrals of marriage and reproduction in an era that highly values traditional family relationships. The success of the magical girl genre implies the society’s embracement of the paradox that resistance to gender roles simultaneously secures the conservativeness of the roles. CONCLUDING REMARKS The magical girl, a popular genre of girls’ television animation program in Japan, has closely reflected shifting ideas of gender roles in society. The classic magical girl anime from the late 1960s and 1970s underscored the interim period of “shōjo” before marriage that allows a girl to enjoy temporal freedom from future obligations as a woman. The new magical girls of the next decade developed the idea that the magical girl’s mission is now solely to be cute and lovable so as to provide viewers in and outside the text visual enjoyment. The visual techniques of transformation rapidly developed, which went hand in hand with concurrent social trends, including the emergence of otaku culture, the popularity of Sanrio-based cute characters, and the increase in women’s deferral of marriage and childbearing. This culture became a foundation for the 1990s magical girl, which explored genre crossing and self-parodies, often featuring gender bending or samegender romance. The contemporary magical girl’s utopian identity, embedded in shōjo-ness, whose power is generated from cuteness, raises questions about the current understanding of the Japanese cool or cute as power. Are these magical girls exploring new gender ideals or demonstrating meaningful alternatives to predetermined gender norms in Japan? Of course, transgressive gender models in the pop media always have the potential to question and mobilize existing 162 Kumiko Saito systems, thereby conceptualizing more performative representations of gender. The conclusion reached in this essay, however, is more skeptical and equivocal. The empowerment of female heroes visualized in the magical girl genre has developed symbiotically with heterosexual norms in society: fighting girls and cross-dressing boys in the magical girl tropes function as counter-agencies to anxieties about conventional gender roles undertaken in reality. In theory, the increasing popularity of the magical girl genre today forecasts the simultaneous growths of Japanese shōjo-ism (defiance to marriage, domesticity, and gender) and conservative gender roles in public discourses of “reality.” The supreme shōjo body does present various possibilities of power and liberation for both women and men, but these potentials materialize as ambivalent mixtures of contesting values, as exemplified by contradictory messages conveyed by metaphors of magic and transformation. In this respect, the magical transformation is a mechanism that bridges utterly different, often opposite, spheres of a seemingly homogeneous society, thereby mending fractures between the media representations of shōjo and gendered reality. List of References AKITA, TAKAHIRO. 2005. “Koma” kara “firumu” e: Manga to manga eiga [From frame to film: Manga and manga films]. Tokyo: NTT Shuppan. ALLISON, ANNE. 2006. Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press. AMANO, MASAKO. 1997. “Women in Higher Education.” Higher Education 34(2):215–35. AZUMA, HIROKI. 2001. Dōbutsukasuru posutomodan: Otaku kara mita Nihon shakai [Otaku: Japan’s database animals]. Tokyo: Kōdansha. ——. 2007. “The Animalization of Otaku Culture.” In Mechademia 2: Networks of Desire, ed. Frenchy Lunning, 175–88. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. BANDAI VISUAL CO. LTD. n.d. “Production Reed Blue-Ray Disk Lineup.” http://www.bandaivisual.co.jp/reed/index.html (accessed December 15, 2008). CHIAVACCI, DAVID. 2005. “Changing Egalitarianism? Attitudes Regarding Income and Gender Equality in Contemporary Japan.” Japan Forum 17(1):107–31. DOLLASE, HIROMI TSUCHIYA. 2003. “Early Twentieth Century Japanese Girls’ Magazine Stories: Examining Shōjo Voice in Hanamonogatari (Flower Tales).” Journal of Popular Culture 36(4):724–55. HAUSMANN, RICARDO, LAURA D. TYSON, and SAADIA ZAHIDI. 2009. “The Global Gender Gap Report 2009.” Economic Forum. http://www.weforum.org/pdf/gendergap/ report2009.pdf (accessed February 18, 2010). HOLLOWAY, SUSAN D., SAWAKO SUZUKI, YOKO YAMAMOTO, and JESSICA DELASENDRO MINDNICH. 2006. “Relation of Maternal Role Concepts to Parenting, Employment Choices, and Life Satisfaction Among Japanese Women.” Sex Roles 54(3/4):235–49. HONDA, MASUKO. 2004. Henbō suru kodomo sekai: Kodomo pawā no hikari to kage [Children’s society in transformation: Light and shadow of child power]. Tokyo: Chūōkōronshinsha. INGLEHART, RONALD, and PIPPA NORRIS. 2003. Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change around the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISHIDA, ATSUKO. 2007. Mahō shōnen Majōrian [Magical boy Majorian], vol. 1. Tokyo: Futabasha. Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis 163 ITŌ, GŌ. 2005. Tezuka izu deddo: Hirakareta manga hyōgenron e [Tezuka is dead: Toward the open expression of manga]. Tokyo: NTT Shuppan. JAPAN INSTITUTE FOR LABOUR POLICY AND TRAINING. 2007. “Shigoto to seikatsu: Taikei-teki ryoritsu shien no kochiku ni mukete.” http://www.jil.go.jp/institute/project/h15-18/ 07/ (accessed February 18, 2010). JAPAN MINISTRY OF HEALTH, LABOUR AND WELFARE. 2009. Business Labor Trend 43 (May). http://www.jil.go.jp/kokunai/blt/backnumber/2009/05/042-044.pdf (accessed February 18, 2010). KINSELLA, SHARON. 1995. “Cuties in Japan.” In Women, Media, and Consumption in Japan, eds. Lisa Skov and Brian Moeran, 220–54. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. KOTANI, MARI. 2006. “Metamorphosis of the Japanese Girl: The Girl, the Hyper-Girl, and the Battling Beauty.” In Mechademia 1: Emerging World of Anime and Manga, ed. Frenchy Lunning, 162–70. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. LOOS, TED. 2000. “Breaking Through Animation’s Boy Barrier.” New York Times. September 17. http://www.nytimes.com/2000/09/17/movies/television-radio-breakingthrough-animation-s-boy-barrier.html (accessed February 18, 2010). LYOTARD, JEAN-FRANçois. 1984. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Translated by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. MCGRAY, DOUGLAS. 2002. “Japan’s Gross National Cool.” Foreign Policy 130 (May/ June):44–54. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2002/05/01/japans_gross_national_cool (accessed February 18, 2010). MINAGUCHI, KISEKO. 2005. Eiga no bosei: Mimasu Aiko o meguru hahaoyazō no nichibei hikaku [Motherhood in film: Japan-US comparison of maternal figures surrounding Mimasu Aiko]. Tokyo: Sairyūsha. MIYADAI, SHINJI. 1993. Sabukaruchā shinwa kaitai: Shōjo, ongaku, manga, sei no 30-nen to komyunikēshon no genzai [The deconstruction of subculture myths: Shōjo, music, manga, thirty years of sexuality, and the present of communication culture]. Tokyo: Parco shuppan. MOSELEY, RACHEL. 2002. “Glamorous Witchcraft: Gender and Magic in Teen Film and Television.” Screen 43(4):403–22. NAPIER, SUSAN JOLLIFFE. 2005. Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF POPULATION AND SOCIAL SECURITY RESEARCH (JAPAN). 2010. “Jinkō tōkei shiryōshū” [Population statistics]. http://www.ipss.go.jp/ (accessed February 18, 2010). NOMAGUCHI, KEI M. 2006. “Time of One’s Own: Employment, Leisure, and Delayed Transition to Motherhood in Japan.” Journal of Family Issues 27(12):1668–1700. OKADA, TOSHIO. 1996. Otakugaku nyūmon [Introduction to otaku studies]. Tokyo: Ōta Shuppan. OSHIYAMA, MICHIKO. 2007. Shōjo manga jendā hyōshōron: “Dansō no shōjo” no zōkei to aidentiti [Representations of gender in shōjo manga: Models and identities of girls in male attire]. Tokyo: Sairyūsha. OTMAZGIN, NISSIM KADOSH. 2008. “Contesting Soft Power: Japanese Popular Culture in East and Southeast Asia.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 8(1):73–101. ŌTSUKA, YASUO. 2001. Sakuga asemamire [Sweat-drenched animators]. Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten. 164 Kumiko Saito SAITŌ, MINAKO. 1998. Kōitten ron: Anime, tokusatsu, denki no hiroinzō [One woman among men: Heroines in anime, tokusatsu, and biographies]. Tokyo: Birejji Sentā Shuppankyoku. SAITŌ, TAMAKI. 2000. Sentō bishōjo no seishin bunseki [Beautiful fighting girl]. Tokyo: Ōta Shuppan. SUZUKI, KAZUE. 1996. “Equal Job Opportunity for Whom?” Japan Quarterly 43(3):54–60. SUZUKI, MICHIKO. 2006. “Writing Same-Sex Love: Sexology and Literary Representation in Yoshiya Nobuko’s Early Fiction.” Journal of Asian Studies 65(3):575–99. TADA, MAKOTO. 2002. Kore ga anime bijinesu da [This is the anime business]. Tokyo: Kōsaidō Shuppan. TAKEUCHI, NAOKO. 1993. Bishōjo senshi Sailor Moon [Pretty soldier Sailor Moon], vol. 3. Tokyo: Kodansha. TŌEI ANIMATION. 2010. “Tōei Animation.” http://www.toei-anim.co.jp/ (accessed October 23, 2013). TSUGATA, NOBUYUKI. 2004. Nihon animēshon no chikara: 85-nen no rekishi o tsuranuku futatsu no jiku [The power of Japanese animation: Two axes that run through eighty-five years of history]. Tokyo: NTT Shuppan. VIDEO RESEARCH LTD. n.d. “Video Research.” http://www.videor.co.jp/ (accessed March 14, 2010). YANO, CHRISTINE R. 2009. “Wink on Pink: Interpreting Japanese Cute as It Grabs the Global Headlines.” Journal of Asian Studies 68(3):681–88. YONEZAWA, YOSHIHIRO. 2007. Sengo shōjo mangashi [Postwar history of shōjo manga]. Tokyo: Chikumashobō.