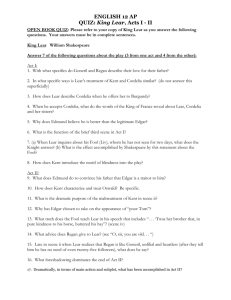

The Meaning of Disguise in Shakespeare's King Lear Several

advertisement

The Meaning of Disguise in Shakespeare’s King Lear Several characters in Shakespeare’s plays undergo transformations that allow for both propelling the works’ momentum and allowing for a social layer to preside within the work. In As You Like It, Rosalind and Celia traverse into the Forest of Arden where they find themselves disguised as lower class citizens, and find truth, innocence and love. In Measure for Measure, the use of disguised is used by the Duke to reveal the innocence of Claudio, and the deceit of Lord Angelo. Yet, King Lear exhibits characters whose disguises make significant class distinctions, favorably casting a positive light on the lower class. Finding himself without a home and caring daughters, King Lear learns to sympathize with a beggar, and unclothes himself in an act to regain his lost innocence. Edgar, the victim of deceit, traverses into the disguise of a beggar with which Lear sympathizes, and dismisses his past identity. He has seen the life of “poor Tom” preserved and deems that the only way he will remain is by disguising himself into that same class (II.vi.20). The banished Earl of Kent disguises himself as a peasant in order to reclaim his association with nobility. Through these characters, a transition into the lower social realm is made through disguise in order to reclaim their lost statuses, and it is in that transitional phase that the audience learns, in different approaches, what the use of disguise means, and what commentary disguise makes on the notion of class. If any elaboration is to be made on the use of disguise in King Lear, defining the term as it adheres to Shakespearean scholars must first be made. In “Disguise in King Lear: Kent and Edgar,” a scholarly journal by Hugh Maclean, he discusses “Disguise in Elizabethan drama [to be] ‘the substitution, overlaying or metamorphosis of dramatic identity, whereby one character sustains two roles; this may involve deliberate or involuntary masquerade, mistaken or concealed identity, madness or possession’” (Maclean 49). In much of Shakespeare’s work, according to Tsuyuki, 2 this definition, the development of one’s character can often be seen as close to the margin of disguise. That said, deciphering among the characters as to which is disguised or not is difficult; Therefore, it is necessary to consult with other scholars’ opinions as to which characters are disguised. Through my research I have found it appropriate that King Lear, Edgar, and Kent are eligible candidates to be elaborated on as being disguised. King Lear discloses the class struggle through Lear, Edgar and Kent, as they, through their disguises, deal with their troubles of being banished from the noble class. It is interesting that Shakespeare utilizes his characters’ disguises only through mobilizing themselves downward. By this, I mean that it is only characters of the upper-class disguising themselves as lower-class citizens. It is negotiable as to whether this commentary on class was intentional by Shakespeare, yet it does allow for a Marxist reading, which issues the interpretation that it is difficult for those of the lower class to socially mobilize upward. This surface level analysis can be further elaborated through the discussion of attire by Kent: “For confirmation that I am much more / than my out-wall (outward appearance)” (III.ii.44-45). Here, Kent makes clear that his disguise as Caius does not define his character beneath the mask. Furthermore, Kent is remarking on the association of characteristics to class, in this case, that one’s physical appearance in terms of attire is what defines the associated upper class. Lear elaborates on the attire of nobility, pointing out Edgar’s lack of silk, leather, wool, and perfume, which transitions into his removal of clothing as a means of sympathizing with the disguised poor Tom (III.vi.96101). The fabrics in which Lear remarks upon clearly distinguish the two classes, as Lear acknowledges through Edgar’s bareness, the socio-economic associations of such fabrics. But what King Lear does not know is that Edgar clearly understands this same distinction, for he is disguised as well. Therefore, the meaning behind the disguise is to illustrate through these Tsuyuki, 3 characters that physical appearance plays a significant role in which class society associates one with. Edgar’s ownership of his own disguise contrasts greatly with Kent. Hugh Maclean states that “Edgar alone is able to combine knowledge and action with the judicious use of disguise. But his capacity is fully revealed only in terms of contrast with Kent” (Maclean 50). Edgar’s use of disguise is grounded upon the notion of time, and it is through his statements of time that his ability to control his disguise is employed. It is interesting that Edgar has to disguise himself out of nobility as a plan to return to it. Even the initial reasoning for his disguise alludes to time as an inevitable construction soon to run out if he remained associated to nobility. In a soliloquy, he states, I will preserve myself; and am bethought / To take the basest and most poorest shape / That ever penury, in contempt of man, / Brought near to beast. My face I’ll grime with filth, / Blanket my loins, elf all my hair in knots, / And with presented nakedness out-face / The winds and persecutions of the sky (II.iii.6-12). The act of preservation, allows for the interpretation that Edgar fears his early demise. Taking on the characteristics of a beggar will “preserve” his life (Holly 175). Also, that this is a plan, “yet” to be executed, confirms his present state as Edgar, which is important in that Edgar’s use of disguise is intentionally employed whereas Lear’s happens unwillingly. And it isn’t until his reentry back into the play (III.vi) that we see this disguise finally taking place. Through his new role as poor Tom, the notion of time is alluded to in its astrological sense: “Bless thee from whirlwinds, star-blasting, and taking!” (III.vi.58). According to footnotes provided by Stephen Greenblatt, these astrological allusions are “capable of causing sickness or death” (Greenblatt 2518). Still fearing his demise, as well as shaping his disguise as poor Tom, Edgar emphasizes Tsuyuki, 4 his “beggar” role by asking for assistance from the King. Once again, the emphasis on Edgar’s own demise is made, rather this time it is done as an act to fool a separate audience – King Lear. Thus, begins the transition through madness for Lear, as he strips off his clothes in an act of sympathy. Important to the meaning of class consciousness through disguise, is the notion of “truth” associating to nakedness. According to Thelma Nelson Greenfield, “nakedness there represented something bad, such as poverty or shamelessness. However, it was also associated with truth-i.e., ‘the naked truth - and so had favorable symbolic meaning’” (Greenfield 282). King Lear undressing can be seen aside from his madness, as a disguise as well, and through nudity, he finds truth. But Greenfield’s statement on truth should be looked at conversely. So, if nakedness is truth, then to be clothed may be associated with deceit. And this is illustrated throughout the play: Goneril and Regan’s plot to remove the King, and Edward’s web of lies to banish his father and rid Edgar of being heir to Gloucester’s estate. Through the notion of truth, comes the essential role of nature, where the disguised characters make further commentary on class. It is in the course of the storm that King Lear loses his clothing and simultaneously loses his power as king. In this scene, we see King Lear and Edgar in there most natural state as men, which, in its theological sense, references man’s innocence as a state only eligible through poverty, and only obtained through confession (Greenfield 282). Confession is certainly acknowledged by Shakespeare through Lear’s awareness of his job as king in terms of the impoverished: “How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides . . . / Defend you from seasons such as these? O, I have ta’en / Too little care of this! Take physic, pomp; / Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel” (III.vi.31-34). It is notable that Shakespeare maintains consistency with the theological meaning behind innocence. In terms of Tsuyuki, 5 time, it would be impossible for the king to have gained his innocence, before making his confession. And the question arises as to whom Lear is confessing? There are several occasions where Edgar is regarded as more than a simple beggar. He is referred to by the Fool as “a spirit” (III.vi.43) and later by King Lear as his “philosopher” (III.v.164). While it is known that Edgar is not a Priest or God himself, the security of nature and all of its innocence allows for the confession to ensue quite conveniently (Bennett 141). Once the confession is made, the undressing of the symbolic clothing associated to nobility and sin takes place: “Off, off, you lendings! come unbutton / here / [stage direction] Tearing off his clothes ” (III.vi.100-02). And finally, King Lear is seen as a desperate character who has now earned his innocence. Kent also employs the use of disguise to make commentary on truth as it pertains to class. In his dialogue with King Lear, he is asked: KING LEAR: What art thou? KENT: A very honest-hearted fellow, and as poor as the king. (I.vi.16-17) And later in that same scene, he furthers this elaboration on honesty in his description of his services to the king: “I can keep honest counsel, ride, run, mar a curious / tale in telling it, and deliver a plain message / bluntly: That which ordinary men are fit for, I am / qualified in; and the best of me is diligence” (I.vi.29-32). By this, Kent is emphasizing the honesty and purity in the lower class citizenry – even a message can be delivered without any manipulation of facts. Yet unlike Edgar’s consistent employment on disguise, Kent’s ownership has flaws that surface the text. This could possibly be that unlike Edgar and King Lear, Kent never had a full noble identity. By this, I mean that Kent was always a servant to the King, and despite this constant association, he remained subservient to his master, much like a beggar. Taking this into consideration, it is understandable why Kent can not decipher between his disguised self and his Tsuyuki, 6 normal self. In fact, he is astonished that Oswald has a difficult time recalling him tripping Oswald and this surprise even angers him into cursing, “What a brazen-faced varlet art thou, to deny thou / knowest me! Is it two days ago since I tripped up / thy heels, and beat thee before the king?” ( II.ii.24-26). Despite Kent’s consistency in wearing his disguise on both occasions, what he fails to acknowledge is that being a simple peasant is just that – nothing important to acknowledge or remember. It is clear that disguise is used in several ways, and carries with it several different meanings. For King Lear, nakedness is a disguise employed to illustrate the essence of man in his most natural state, which calls upon the notions of truth, and differentiates the classes according to truth. Through Edgar, disguise is used purposefully in order to preserve one’s self, and through self preservation, the restoration of his nobility is surfaced, thus eliminating the corrupt elites who once presided. Kent’s character, through all of his flaws as a masked man, allows the audience to grasp the difficulty in employing disguise, as he constantly remarks on his own. His flaws allow the audience to become aware of the social stratifications in the play, through the understanding that Kent’s transition into the lower class was not as vast as the King’s or Edgar’s, for he was always a servant to some extent. It is remarkable how each character makes commentary on class in different ways, and how through the added dimension of disguise, the layers of interpreting King Lear become evermore penetrating. Tsuyuki, Works Cited Bennett, Josephine Waters. “The Storm Within: the Madness of Lear.” Shakespeare Quarterly 13.2 (Spring, 1962): 137-155. Greenblatt, Stephen, ed. “King Lear.” The Norton Shakespeare: Based on the Oxford Edition. New York: Norton, 1997. Greenfield, Thelma Nelson. “The Clothing Motif in King Lear.” Shakespeare Quarterly 5.3 (Summer, 1954): 281-286. Holly, Marcia. “King Lear: The Disguised and Deceived.” Shakespeare Quarterly 24.2 (Spring, 1973): 171-180. Maclean, Hugh. “Disguise in King Lear: Kent and Edgar.” Shakespeare Quarterly 11.1 (Winter, 1960): 49-54. 7