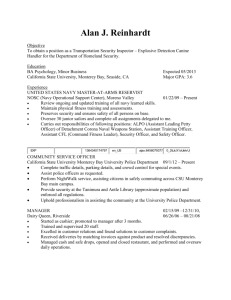

Basic Military Requirements

advertisement