Nicholson v. Williams

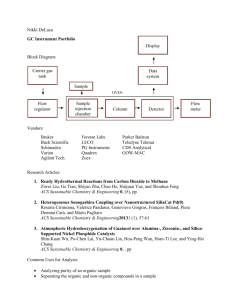

advertisement