Market-sensing capability and market orientation in the food industry

advertisement

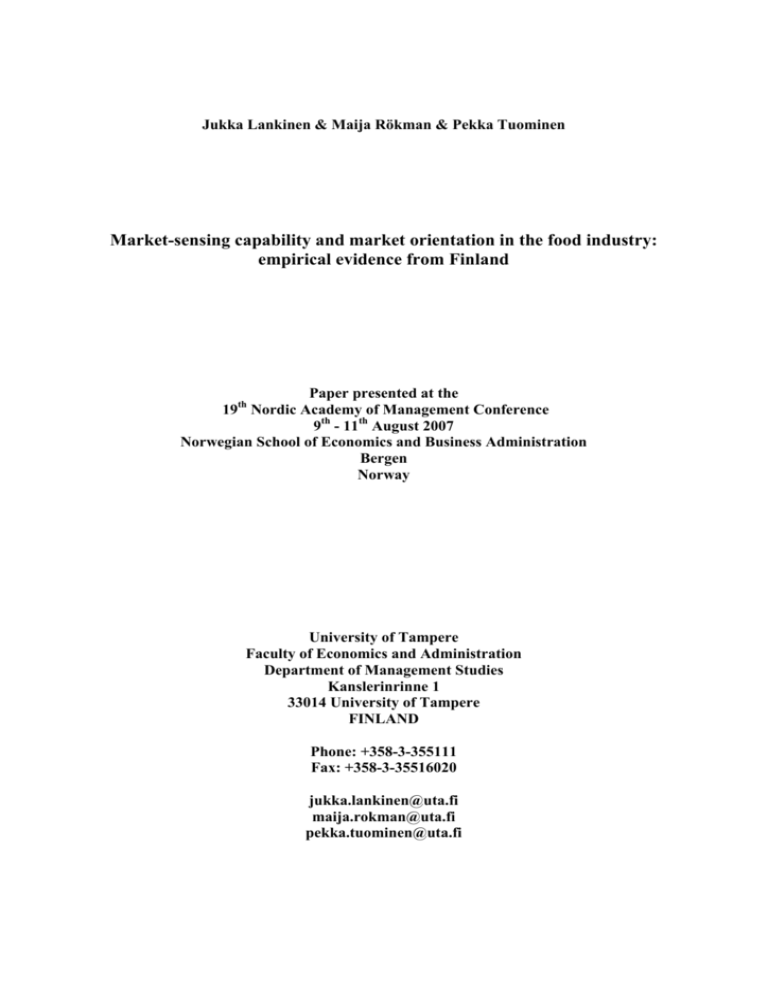

Jukka Lankinen & Maija Rökman & Pekka Tuominen Market-sensing capability and market orientation in the food industry: empirical evidence from Finland Paper presented at the 19th Nordic Academy of Management Conference 9th - 11th August 2007 Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration Bergen Norway University of Tampere Faculty of Economics and Administration Department of Management Studies Kanslerinrinne 1 33014 University of Tampere FINLAND Phone: +358-3-355111 Fax: +358-3-35516020 jukka.lankinen@uta.fi maija.rokman@uta.fi pekka.tuominen@uta.fi Market-sensing capability and market orientation in the food industry: empirical evidence from Finland 1 INTRODUCTION The food industry is the fourth largest branch of industry in Finland after metal and engineering, forest and chemical industries. The Finnish food industry is the biggest manufacturer of consumer goods. The largest production sectors of the food industry are meat processing, dairy products, bakery, brewing and soft drinks industry. In Finland the food industry operates in approximately 2.000 firms. Almost 70 per cent of all firms in the food industry employ less than 5 employees and less than 30 firms have more than 250 employees (www.etl.fi). Almost 85 per cent of the raw material used by the Finnish food industry is domestic. The market share of Finnish food products in Finland is 83 per cent. The Finnish food industry employs 36.300 wage and salary earners and it is the third important employer among industries. The whole Finnish food chain employs over 300.000 persons and this amounts 13 per cent of the whole employed labour force in Finland (www.etl.fi). The most important export products of the Finnish food industry are cheese, butter, chocolate, sugar-derived products, meat and alcoholic drinks. The most important export countries are Russia (22 %), Sweden (15 %), Estonia (10 %), USA (5 %) and Germany (5 %). The value of food exports in 2006 was 1.2 billion euro (www.etl.fi). The purpose of this study is to describe and analyse market-sensing capability and market orientation in the Finnish food industry in the Tampere region. First, we analyse the empirical components of the market-sensing capability. Second, we provide empirical dimensions in collecting and analysing market information. Finally, we provide conclusions and managerial implications. 2 THE CONCEPT OF MARKET ORIENTATION Market orientation emerged as a distinct theme in the discipline of marketing in the beginning of the 1990s and there is a substantial literature on it (Kohli & Jaworski 1990; Slater & Narver 1995; Renko 2006). Market orientation has its roots in both economics and the social exchange view of markets. The underlying assumption is that profit maximisation and long-term profitability are the ultimate goals of sellers. At the same time, however, these goals can only be achieved by understanding customers’ needs as well as competitors’ strategies (Helfert & Ritter & Walter 2002; Lafferty & Hult (2001); Renko 2006; Schlosser & McNaughton 2007; Selnes & Jaworski & Kohli (1996). Classical definition for market orientation is related to the extent to which an actor in the marketplace uses knowledge about the market, especially about customers, as a basis for decisionmaking on what to produce, how to produce, and how to market it (Jaworski & Kohli 1993; 1996; Kohli & Jaworski 1990). Market-oriented firms seek to understand customers’ expressed and latent needs and develop superior solutions to those needs (Slater & Narver 1999). According to Jaworski & Kohli (1993) firm’s market orientation builds upon three dimensions: the organisation-wide acquisition, dissemination and co-ordination of market intelligence. Advocates of the market orientation approach believe that analysing the competitive environment of a firm can generate exceptional advantages that lead to good business performance (Beverland & Lindgren 2007). The two major streams of thoughts in market orientation are cultural and behavioural market orientation (Renko 2006). However, this is not the only way to categorise the existing research in the field. According to Hurley & Hult (1998), researchers have approached market orientation from a strategy perspective, an organizational design perspective, and a market information processing perspective. Lafferty & Hult (2001) identified the following five attempts to conceptualise the concept of market orientation: the decision-making perspective; the market intelligence perspective, the culturally-based behavioural perspective; the strategic focus perspective, and the customer perspective. There are two approaches to being market oriented: a market-driven approach and a driving-market approach. Market-driven refers to a market orientation that is based on understanding and reacting to the preferences and behaviours of actors within a given market structure. Driving markets, on the other hand, implies influencing the structure of markets and/or the behaviours of actors in a direction that enhances the competitive position of the firm (Jaworski & Kohli & Sahay 2000). Consequently, being market oriented incorporates both reactive and proactive behaviour (Sandberg 2005; Slater & Narver 1998). The main separating element between reactiveness and proactiveness towards the market seems to be time. Reactiveness towards the market means that the firm is market-driven. It accepts the market structure as given and does not aim to change market behaviour. Proactiveness towards the market includes both anticipating and influencing. This means that the firm is market-driving. In terms of reactiveness and proactiviness towards the market, the key issue is whether customer behaviour is reacted to, anticipated or influenced (Jaworski & Kohli & Sahay 2000; Kumar & Scheer & Kotler 2000; Sandberg 2005). 3 THE CONCEPT OF MARKET-SENSING CAPABILITY Market-driving firms are distinguished by ability to sense events and trends in their markets ahead of their competitors. They can anticipate more accurately the responses to actions designed to retain or attract customers, improve channel relations or thwart competitors (Jaworski & Kohli & Sahay 2000). They can act on information in a timely, coherent manner because the assumptions about the market are broadly shared. This anticipatory capability is achieved through open-minded inquiry, synergistic information distribution and mutually informed interpretations about the market. Day (1994) defines this distinctive capability as market sensing. It can provide a firm with an edge over its competitors. It is easy to encounter firms in trouble because they have faulty or inadequate information about their markets (Anderson & Narus 2007). Market sensing can be defined as a process of generating knowledge about the markets that individuals in the firm use to inform and guide their decision-making. Market-sensing is a process of learning about present and prospective customers and competitors. Market sensing enables firms to formulate, test, revise, update and refine their market views, which are simplified representations of the market and how it works (Anderson & Narus 2007). Market sensing greatly contributes to the market knowledge by providing a way to test assumptions about customers, competitors and the firm’s own resources and capabilities that often are largely implicit. Substantive facets in market sensing include (1) defining the market; (2) monitoring competition; (3) assessing customer value; and (4) gaining customer feedback. To attain a distinctive capability in market sensing, the firm should strive to be superior to its competitors in each of these facets (Anderson & Narus 2007). Our study is based on the theoretical model of market-sensing capability proposed by Foley & Fahy (2004). This model has been constructed from the ideas of Day 1994; Sinkula & Baker & Noordewier (1997) and Day & Van den Bulte (2002). The Foley and Fahy model dissects the market-sensing capability in order to facilitate understanding of how market orientation is created. Market-sensing capability is comprised of four components: first, learning orientation with a commitment to learning, open-mindedness in learning and shared visions; secondly, organisational systems with decentralisation in decision-making, formalisation of decision-making rules, use of reward systems and benchmarking activities; thirdly, market information with development of a market information system; and finally organisational communication with organisational values and clear decision-making criteria. These various components of the market-sensing capability are illustrated in Figure 1 (Foley & Fahy 2004, 224). MARKET-SENSING CAPABILTY Learning orientation • Commitment • Open-mindedness • Shared vision Organisational system • Decentralisation • Formalisation • Reward systems • Benchmarking MARKET ORIENTATION Market information • Development of market information system Organisational communication • Organisational values • Decision-making criteria Figure 1. The components of the market-sensing capability (Source: Foley & Fahy 2004, 224) All components of market-sensing capability with their sub-components have a specific resonance in market-sensing. We propose that the market-sensing capability acts as a precondition for market orientation. 4 CONDUCTING THE EMPIRICAL STUDY The empirical data was collected by a mail survey from all the food industry companies in the Tampere region in March 2006. The use of a mail survey was deemed appropriate because it provided an opportunity for respondents to give considered answers. We used in the questionnaire a quantitative attribute-based measurement approach, with a 5-point Likert scale. We utilised the Likert scale because it is widely used and respondents readily understand it (Aaker & Kumar & Day 2007; McDaniel & Gates 2006). The original 4-page questionnaire was piloted in small focus groups. 176 questionnaires were mailed. Altogether 39 questionnaires were returned on time. The response rate was 22 per cent. This can be regarded as rather fair when dealing with the response from the management in industry. No reminders were used because we wanted to secure the anonymity of all responding firms. Unfortunately, 10 questionnaires had to be rejected as they contained insufficient information. Therefore, there were 29 applicable questionnaires for the study. However, when measuring by the turnover, these firms account for 56 per cent of the markets in the food industry in the Tampere region. The quantitative data was statistically analysed using the SPSS package. The methods of the data analysis include frequencies, means, standard deviations, analysis of variance, correlations and factor analysis. We will use the empirical results of the quantitative study to modify the theoretical model of market-sensing capability for the food industry in the Tampere region. 5 THE EMPIRICAL COMPONENTS OF MARKET-SENSING CAPABILITY The companies in the food industry of the Tampere region performed rather well in market-sensing and were to a considerable extent market-oriented. Some problems were found in each of the four components but in general the level of market-sensing can be regarded as high. Figure 2 illustrates the empirical components of market-sensing capability in the food industry of the Tampere region. These companies were relatively learning-oriented. In general, there was a high commitment to learning especially among the management. The companies’ openness towards learning is relatively high with the regard to both internal and external sources of information. The internal operations in the food industry companies were strongly market-oriented, but still some areas for improvement were found. The decentralisation of decision-making is not very common in the companies. Heavy reliance was placed on formal rules which were respected by the personnel. The use of reward systems should clearly be improved. In addition, some benchmarking activities can be regarded as inadequate. The companies do not actively provide information to other members of the supply chain although the exchange of information is considered not harmful for the company’s operations. Collecting and analysing market information fell clearly into two different categories among the companies in the food industry. Some companies collect and analyse market information actively, whereas some others collect market information and analyse it rather unsystematically. Alarmingly, the market information collected and analysed does not usually lead to any improvements or practical measures. Organisational communication in these companies is quite efficient. Information is disseminated widely and rather openly in the companies. The values of the companies are market-oriented. However, not enough attention is paid to key customers. MARKET-SENSING CAPABILITY Learning orientation • Commitment o The personnel and especially the management are committed to learning • Open-mindedness o Various sources of information o Use of databases to be intensified o Action models not often questioned • Shared vision Organisational system • Decentralisation o Decision-making is too centralised • Formalisation o The personnel put it into practice and support it • Reward systems o Clearly insufficient • Benchmarking o Much to improve o More analysis to be done MARKET ORIENTATION Market information • Development of market information systems o More information collecting and analysis to be done Organisational communication • Organisational values o Market-oriented values o Norms are recognised and followed • Decision-making criteria o Open flow of information o Value of key customers is not emphasised enough Figure 2. Market-sensing capability in the food industry of the Tampere region Companies in the Tampere region act rather similarly in market-sensing regardless of their size. No significant differences were found between small, medium and large companies. A lack of resources is often an evident reason for differences in the market-sensing capability between companies of different sizes. Large and medium-sized companies often have more monetary and personal resources at their disposal for market-sensing. 6 EMPIRICAL DIMENSIONS IN COLLECTING AND ANALYSING MARKET INFORMATION After the preliminary analysis, in which frequencies, percentages, means, standard deviations, and correlations were calculated, factor analysis was conducted. The aim was to reduce the number of individual 5-point Likert scale variables. Factor analysis was employed to reduce the dimensionality of the original criteria to a smaller number of factors by forming a linear combination of the original data while retaining as much variance as possible (Aaker & Kumar & Day 2007; Malhotra & Birks 2007; Schmidt & Hollensen 2006). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure was 0.71, and Bartlett’s test of spherity was 485 (significance 0.00). Kraiser’s eigenvalue criterion was used in determining the number of factors. The factor analysis isolated three factors based on eigenvalues over 1.00. The factor matrix was rotated with the orthogonal method of varimax rotation because this method spreads variance evenly among factors (Malhotra & Birks 2007; McDaniel & Gates 2007; Schmidt & Hollensen 2006). With the three factors the total percentage of explained variance was 76 per cent. Communalities of the original variables were quite high. The factor analysis brought up three factors that represent empirical dimensions in collecting and analysing market information. These factors were named and interpreted based on the highest factor loadings as follows: (1) Activity in collecting market information, (2) Insufficiency in collecting market information, and (3) Reluctance in disseminating market information. Table 1 depicts the three empirical dimensions in collecting and analysing market information. In this table, the rows refer to different variables. Table 1. Empirical dimensions in collecting and analysing market information Activity in collecting market information Insufficiency in collecting market information Reluctance in Commudisseminating nality market information Our company actively collects information about customers Our company actively analyses market information Our company constantly collects market information We receive much information from the other members in the distribution chain Our company actively analyses other companies’ values Our company actively analyses other companies’ attitudes The collected and analysed information always leads to measures Our company actively analyses other companies’ leadership styles Our company constantly collects information about consumers Our company actively analyses information about competitors Our company actively collects information about competitors Our company actively analyses information about customers Our company actively provides information to other members of the distribution chain Our company actively analyses information about consumers Sensing changes in the market is relevant for our business Our company should attach more weight to information collecting in the future We aim to pay more attention to information collecting in the future Our company collects market information randomly Exchanging information between companies in the distribution chain can be harmful to our company 0.91 0.84 0.90 0.87 0.88 0.80 0.88 0.85 0.88 0.86 0.87 0.79 0.86 0.74 0.86 0.83 0.85 0.77 0.84 0.78 0.84 0.79 0.83 0.72 EIGENVALUE 10.53 EXPLAINED VARIANCE 55 % 0.79 -0.33 0.75 0.62 0.32 0.50 0.60 0.49 0.62 0.93 0.94 0.86 0.74 0.69 0.53 0.85 0.76 2.78 1.18 14.49 15 % 6% 76 % 7 CONCLUSIONS AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS Companies in the food industry in the Tampere region, especially the smaller ones, should pay greater attention on collecting and analysing market information in the future. Collecting and analysing the information was frequently rather poor in these firms. The information collected and analysed did not always lead to concrete measures for improving the business by strengthening market orientation and competitive advantage. In the future, more effort should be focused on improving reward systems for the personnel. Most companies did not have a functioning reward system. If the rewarding strategy included also nonpecuniary means, the costs would hardly increase. The use of customer databases should be intensified in the food industry. Even larger companies do not take enough advantage of the potential provided by the customer databases. Even 43 per cent of the larger companies did not use customer databases for obtaining market information. One partial explanation for this might be the insufficiency or lack of customer databases in the companies. The use of customer databases would enable the food companies to improve their market orientation as well as customer management. REFERENCES Aaker, D. & Kumar, V. & Day, G. (2007) Marketing research. John Wiley & Sons: New York. Anderson, J. & Narus, J. (2007) Business market management. Understanding, creating and delivering value. Prentice Hall: New York. Beverland, M. & Lindgreen, A. (2007) Implementing market orientation in industrial firms: a multiple case study. Industrial Marketing Management Vol. 36, No. 4, 430-442. Day, G. (1994) The capabilities of market-driven organizations. Journal of Marketing Vol. 58, No. October, 37-52. Day, G. & Van den Bulte, C. (2002) Superiority in customer relationship management: consequences for competitive advantage and performance. Marketing Science Institute Vol. 41, No. 2, 31-44. Foley, A, & Fahy, J. (2004) Towards a further understanding of the development of market orientation in the firm: a conceptual framework based on the market-sensing capability. Journal of Strategic Marketing Vol. 12, No. 4, 219-230. Helfert, G. & Ritter, T. & Walter, A. (2002) Redefining market orientation from a relationship perspective. Theoretical considerations and empirical results. European Journal of Marketing Vol. 36, No. 9/10, 1119-1139. Hurley, R. & Hult, G. (1998) Innovation, market orientation and organizational learning. An integration and empirical examination. Journal of Marketing Vol. 62. No. July, 42-54. Jaworski, B. & Kohli, A. (1993) Market orientation: antecedents and consequences. Journal of Marketing Vol. 57, No. July, 53-70. Jaworski, B. & Kohli, A. (1996) Market orientation: review, refinement and roadmap. Journal of Market-focused Management Vol. 1, No. 2, 119-136. Jaworski, B. & Kohli, A. & Sahay, A. (2000) Market-driven versus driving markets. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science Vol. 28, No. 1, 45-54. Kohli, A. & Jaworski, B. (1990) Market orientation: the construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. Journal of Marketing Vol. 54, No. April, 1-18. Kumar, N. & Scheer, Li. & Kotler, P. (2000) From market driven to market driving. European Management Journal Vol. 18, No. 2, 129-142. Lafferty, B. & Hult, T. (2001) A synthesis of contemporary market orientation perspectives. European Journal of Marketing Vol. 35, No. 1/2, 92-109. Malhotra, N. & Birks, D. (2007) Marketing research. An applied approach. Prentice Hall: London. McDaniel, C. & Gates, R. (2006) Marketing research: essentials. John Wiley & Sons: New York. McDaniel, C. & Gates, R. (2007) Marketing research with SPSS. John Wiley & Sons: New York. Renko, M. (2006) Market orientation in markets for technology – evidence from biotechnology ventures. Publications of the Turku School of Economics. Series A-8:2006. Turku. Sandberg, B. (2005) The hidden market – even for those who create it? Customer-related proactiveness in developing radical innovations. Publications of the Turku School of Economics. Series A-5:2005. Turku. Schlosser, F. & McNaughton, R. (2007) Individual-level antecedents to market-oriented actions. Journal of Business Research Vol. 60, No. 5, 438-446. Schmidt, M. & Hollensen S. (2006) Marketing research. An international approach. Prentice Hall: London. Selnes, F. & Jaworski, B. & Kohli, A. (1996) Market orientation in United States and Scandinavian companies: a cross-cultural study. Scandinavian Journal of Management Vol. 12, No. 2, 139-157. Sinkula, J. & Baker, W. & Noordewier T. (1997) A framework for market-based organizational learning: linking values, knowledge and behaviour. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science Vol. 25, No. 4, 305-318. Slater, S. & Narver, J. (1995) Market orientation and the learning organization. Journal of Marketing Vol. 59, No. July, 63-75. Slater, S. & Narver, J (1998) Customer-led and market-oriented: Let’s not confuse the two. Strategic Management Journal Vol. 19, No. 10, 1001-1006. Slater, S. & Narver, J. (1999) Market-oriented in more than being customer-led. Strategic Management Journal Vol. 20, No. 12, 1165-1168. www.etl.fi/english <12.06.2007>