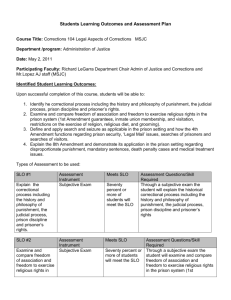

the “special needs” of prison, probation, and parole

advertisement