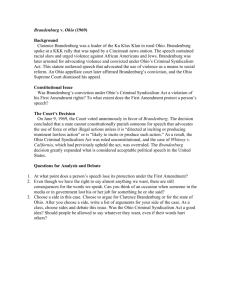

Can Brandenburg v. Ohio Survive the Internet and the Age of

advertisement