2.3. PSYCHIATRIC APPROACH

The serial murderer’s personality develops through a combination of specific variables

that feed upon themselves, creating a feedback loop for the activity.

Insanity, as is well known, is but a legal distinction. It usually refers to a person’s ability

to appreciate wrongfulness and refrain from certain impulses. A trademark of the serial

murderer is the conscious recognition of the illegality of his actions, while he conducts

his predatory lifestyle with continued concerns regarding avoidance of detection.

So he is no less alleviated of criminal ways, regardless of existing laws, and is not

exempt from culpability.

Precautions such as Dahmer’s security system, Gacy and

Nilsen’s disposal methods, or other offenders’ proud display of bodies for authorities to

find are not behaviours of people unable to recognize the wrongfulness of their actions.

A suggested diagnostic category, named Homicidal Pattern Disorder, should be listed

under “Impulse-Control Disorders Not Elsewhere Classified” (American Psychiatric

Association, 1994). The accompanying discussions of etiology would ni clude issues

such as biology, environment, and sexual dysfunction, intimacy, esteem difficulty and

dissociative process.

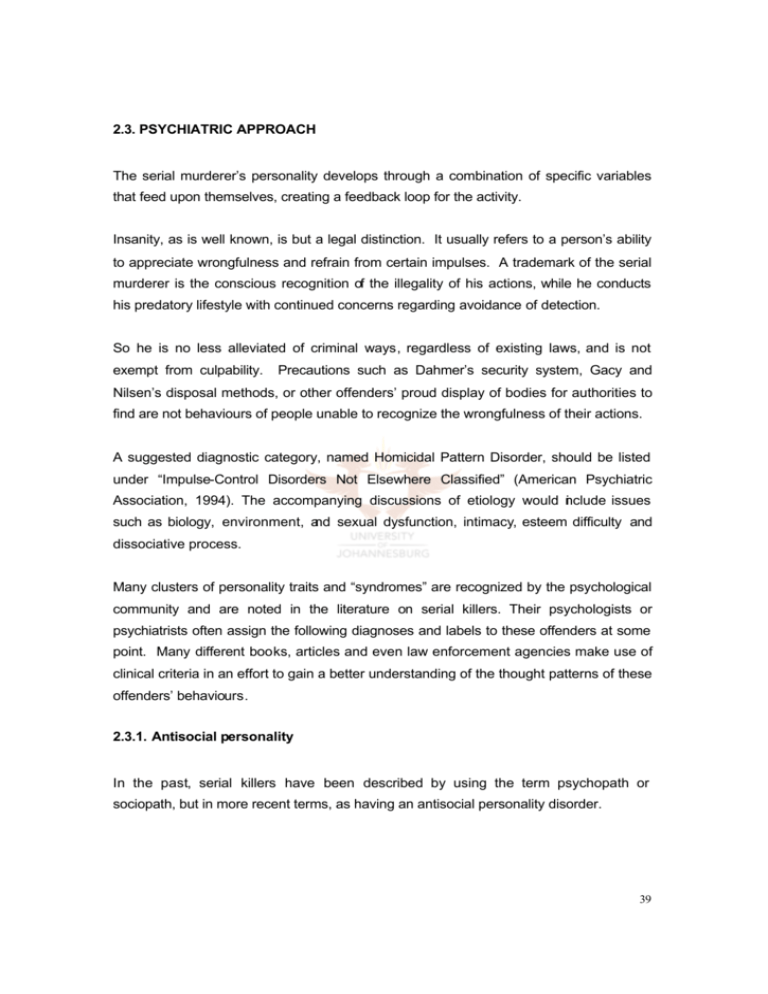

Many clusters of personality traits and “syndromes” are recognized by the psychological

community and are noted in the literature on serial killers. Their psychologists or

psychiatrists often assign the following diagnoses and labels to these offenders at some

point. Many different books, articles and even law enforcement agencies make use of

clinical criteria in an effort to gain a better understanding of the thought patterns of these

offenders’ behaviours.

2.3.1. Antisocial personality

In the past, serial killers have been described by using the term psychopath or

sociopath, but in more recent terms, as having an antisocial personality disorder.

39

The antisocial personality disorder diagnosis further requires at least four to nine

manifestations of the disorder after the age of 18 years.

This disorder is seen as rarely leading to murder. Individuals identified as sexual sadists

may find fantasized sadomasochistic activity sexually arousing or satisfying.

It is,

presumably, the combination of antisocial personality disorder and sexual sadism that

creates the potential for acting out sexually sadistic impulses, that is, the commission of

serial murders.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, or the DSM–IV (1994), criteria for

this disorder include the following:

Table 2.3.1.

Diagnostic criteria for Antisocial Personality Disorder

A. There is a pervasive pattern of disregard for, and violation of, the rights of others

occurring since the age of 15 years, as indicated by three (or more) of the following:

1. Failure to conform to social norms with respect to lawful behaviours as indicated by

repeatedly performing acts that are grounds for arrest

2. Deceitfulness, as indicated by repeated lying, use of aliases, or conning others for

personal profit or pleasure

3. Impulsivity or failure to plan ahead

4. Irritability and aggressiveness

5. Reckless disregard for the safety of others or self

6. Consistent irresponsibility, as indicated by repeated failure to sustain work behaviour

or honour financial obligations

7. Lack of remorse, as indicated by indifference to or rationalizing having hurt,

mistreated, or stolen from another

B. Individual must at least be 18 years of age

C. The occurrence of the behaviour is not exclusive during the course of a

schizophrenic or manic episode

D. Evidence of conduct disorder onset before age 15

40

These criteria are particularly relevant to serial killers, as many such offenders share

childhoods coloured with behaviour consistent with conduct disorder, such as

aggression to people and animals, forced sexual activity, and fire setting (DSM-IV,

1994). Key elements shared by antisocial personality, sociopaths, and serial killers are a

failure to conform to social norms regarding the lawful behaviour, physical

aggressiveness, impulsivity, lack of regard for the truth, manipulativeness, and most of

all, lack of remorse or empathy. Some serial killers report remorse after the commission

of some crimes, but never to the point of changing their behaviour, e.g. Dahmer, Bundy,

Fish and others. This can be seen by their behaviour in court, after incarceration.

Causal factors for an antisocial personality include a possible biological predisposition

(Andreasen, 1984), childhood trauma (shared by a vast majority of serial killers),

possible neurological factors in the control of impulsivity regarding serotonin levels in the

brain, and heredity.

According to the personal interviews by Havens (in Giannangelo, 1996), these serial

killers also have deep-seated doubts regarding their own adequacy, and most

antisocials seem to be men, thus also reflecting serial killer demographics. To describe a

serial killer only as an antisocial personality is, however, a major error on the

researcher’s part. Many if not most of the prison population can be described as such,

as well as many of the “average” citizens not incarcerated. This clustering trait is helpful;

however, it adds to the overall profile and suggests possible consistencies and

etiologies, but the criteria should not be overrated.

2.3.2. Borderline personality

Borderline personality disorder is the most comparable to antisocial personality disorder

as this includes a pervasive pattern of instability in interpersonal relationships, selfimage, affects and marked impulsivity.

The patterns begin by early adulthood and are present in a variety of contexts, as

indicated by the presence of at least five of the following (DSM-IV, 1994):

41

Table 2.3.2.

Diagnostic criteria for Borderline Personality Disorder

A pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects,

marked impulsivity beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as

indicated by five (or more) of the following:

1. Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. Note: Do not include suicidal

or self-mutilating behaviour covered in Criterion 5.

2. A pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterized by

alternating between extremes for idealization and devaluation

3. Identity disturbance: markedly and persistently unstable self-image or sense of self

4. Impulsivity in at least two areas that are potentially self-damaging (e.g. spending,

sex, substance abuse, recklessness, binge eating). Note: Do not include suicidal or

self- mutilating behavior covered in Criterion 5.

5. Recurrent suicidal behaviour, gestures, threats or self-mutilating behaviour

6. Affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood (e.g. intense episodic

dysphoric, irritability or anxiety usually lasting a few hours and only rarely more than

a few days)

7. Chronic feelings of emptiness

8. Inappropriate, intense anger or difficulty controlling anger (e.g. frequent displays of

temper, constant anger, recurrent physical fights)

9. Transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms

(DSM -IV, 1994, p. 654)

Again, these include a defective sense of identity and extreme instability. The sufferer

often views the world as “all good” or “all bad”. This description is more often found in a

large percentage of female serial killers, especially those acting as ‘angels of mercy’,

who attempt to right the wrongs of the world or who seek revenge and owe the world a

payback. Though a borderline disorder is more often diagnosed in women, it is not

exclusively so. Jeffery Dahmer was diagnosed by prison psychiatrists as having features

of this disorder (Dvorchak and Holewa, 1991). Dr Rappaport described John Wayne

Gacy as having a borderline personality disorder, deduced from his childhood history

and the manner in which he committed the crimes. These illustrated a primitive ego

42

defense common to borderlines: the progress from simple projection to projective

identification (Cahill, 1986). Causal factors in borderlines include a history of incest or

other sexual abuse and a proneness to experiencing dysphoria, or a generalized feeling

of ill-being, as well as abnormal anxiety, discontent or physical discomfort.

Both antisocials and borderlines display gross deviation from normal attachment

processes, which results in a disinhibition of violence (Meloy, 1992). The borderline will

be pathologically attached, whereas the antisocial at the other end of the spectrum, will

be pathologically detached.

2.3.3. The psychopathic personality

According to Meloy (1992), the terms antisocial and psychopathic should not be used

interchangeably. Psychopathy is diagnosed in about one out of three incarcerated

individuals and is a far more severe psychological condition in terms of symptoms and

treatment. The psychopathic offender appears predisposed to predatory violence and is

the classic serial killer personality.

The psychopath is a personality incorporating both aggressive narcissism and extended

chronic antisocial behaviour over time. The personal trails of psychopaths usually show

a trail of used, injured and hurt people as these individuals are in a continuous effort to

build their own fragile sense of self.

As the DSM-IV provides us with criteria for the personality disorders, so has Robbert

Hare (1991) provided us with the following checklist in identifying a psychopath. It is said

that most of these traits if not all are found in the serial killer personality.

•

Glibness and superficial charm

•

Grandiosity

•

Continued need for stimulation

•

Pathological lying

•

Conning and manipulativeness

•

Lack of remorse or guilt

•

Shallow affect

43

•

Callous lack of empathy

•

Parasitic lifestyle

•

Poor behaviour controls

•

Promiscuity

•

Early behavioural problems

•

Lack of realistic long-term goals

•

Impulsivity

•

Irresponsibility

•

Failure to accept responsibility for actions

•

Many short-term relationships

•

Juvenile delinquency

•

Revocation of conditional release

•

Criminal versatility

This checklist identifies internal as well as external characteristics, and then the traits of

an antisocial personality. A difference stated by Hare (1993) between the antisocial and

the psychopath is that even though both are violent, the psychopath is more frequently

and more severely violent. This violence continues until it reaches a plateau at age 50 or

so, whereas the psychopath does not seem to reach such a plateau.

A key aspect of the psychopath with regard to serial killers is that the violence tends to

be predatory and primarily on a stranger-to-stranger basis. The violence is planned,

purposeful and emotionless. This emotionlesness reflects a detached, fearless and

possibly dissociated state, revealing a lower autonom ic nervous system and the lack of

anxiety (Kaplan, et al, 1994). The general motivation is to dominate and to control; his

history will thus also show one or no bond with others.

According to Meloy (1992), sexually, psychopaths continue their grandiose demeanour

and are hyper-aroused automatically, which causes them to seek the sensation

continuously. Together with the fact that psychopaths display a propensity for sadism,

their lack of bonding reflects a lack of emotionality and a diminished capacity for love,

thus the objectification and devaluation of sexual partners.

44

2.3.4. Narcissistic personality

The DSM-IV describes the narcissistic personality as having a pervasive pattern of

grandiosity (in fantasy or in behaviour), with the need for admiration. The pattern begins

by early childhood, and is present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by at least five of

the following (1994):

Table 2.3.4.

Diagnostic criteria for Narcissistic Personality Disorder

A pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behaviour), the need for admiration, and

the lack of empathy, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts,

as indicated by five (or more) of the following:

•

Has a grandiose sense of self-importance (e.g. exaggerates achievements and

talents, expects to be recognized as superior without commensurate achievements)

•

Is preoccupied with fantasies of unlimited success, power, brilliance, beauty or ideal

love

•

Believes that he or she is “special” and unique and can only be understood by, or

should associate with, other special or high status people (or institutions)

•

Requires excessive admiration

•

Has a sense of entitlement, i.e. unreasonable expectations of especially favourable

treatment or automatic compliance with his or her expectations

•

Is interpersonally exploitive, i.e. takes advantage of others to achieve his or her own

ends

•

Lacks empathy: is unwilling to recognize or identify with the feelings and needs of

others

•

Is often envious of others or believes that others are envious of him or her

•

Shows arrogant, haughty behaviours or attitudes

(DSM -IV, 1994)

Most of these traits can be found in the serial killer’s personality (i.e. Bundy). Aggressive

narcissism is pervasive in the classic psychopath, and features a pronounced sadistic

streak (Meloy, 1992). Gacy was also among these diagnosed with such features (Cahill,

1986).

45

2.3.5. Obsessive- Compulsive personality

Another pattern that seems to emerge with serial killers is the presence of obsessivecompulsive traits.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder can manifest itself in obsessions,

defined as recurrent and persistent ideas, thoughts, impulses or images, and

experienced at least initially as intrusive and senseless (Gianangelo, 1993).

In addition, the thoughts, impulses or images are not simply excessive concerns about

real-life problems; the person attempts to ignore or suppress such thoughts or impulses

or to neutralize them with other thoughts or actions, e.g. Albert Fish. The person

recognizes these obsessions as a product of his or her own mind (DSM-IV, 1994).

Table 2.3.5.

Diagnostic criteria for Obsessive -Compulsive Disorder

A. Either obsessions or compulsions

Obsessions as defined by (1), (2), (3), and (4):

1. Recurrent and persistent thoughts, impulses or images that are experienced, at

some time during the disturbance, as intrusive and inappropriate and that cause

marked anxiety or distress

2. The thoughts, impulses or images are not simply excessive concerns about real

life problems

3. The person attempts to ignore or suppress such thoughts, impulses or images, or

to neutralize them with some other thought or action

4. The person recognizes that the obsessional thoughts, impulses or images are a

product of his or her own mind (not imposed from without, as in thought insertion)

Compulsive as defined by (1) and (2):

1. Repetitive behaviours (e.g. hand washing, ordering, checking) or mental acts

(e.g. praying, counting, repeating words silently) that the person feels driven to

perform in response to an obsession, or according to rules that must be applied

rigidly

2. The behaviours or mental acts are aimed at preventing or reducing distress or

preventing some dreaded event or situation. However, these behaviors or mental

46

acts either are not connected in a realistic way with what they are designed to

neutralize or prevent or are clearly excessive

B. At some point during the course of the disorder, the person has recognized that

the obsessions or compulsions are excessive or unreasonable. Note: This does

not apply to children.

C. The obsessions or compulsions cause marked distress, are time consuming

(take one hour a day), or significantly interfere with the person’s normal routine,

occupational (or academic) functioning, or usual social activities or relationships.

Further criteria, not for the purpose of this section.

(DSM-IV, 1994)

Also apparent are compulsions defined by repetitive, purposeful and intentional

behaviours performed in response to an obsession according to certain rules or in a

stereotyped fashion. The behaviour is designed to neutralize or prevent discomfort or

some dreaded event or situation; however, the activity is not connected in a realistic way

with what it is designed to neutralize or it is clearly excessive. The person also realizes

that his or her behaviour is excessive or unreasonable (DSM-IV, 1994).

A number of ongoing life patterns, such as overperfectionism; preoccupation with details,

order and organization; the unreasonable insistence that others follow his or her way of

doing things; indecisiveness; overinclusiveness; and inflexibility, are all similar

behavioural patterns in a small scale (obsessive-compulsive disorder). Furthermore, a

restricted expression of affection, miserly hoarding money and a reluctance to delegate

tasks or work with others has also been noted.

It is said that obsessive-compulsive people often have problems expressing aggressive

feelings and thus stifle these, causing an implosion of emotions that could cause internal

damage. They often have a history of stress, are usually male and are most often

children of people with obsessive-compulsive or personality disorders. The obsessive-

47

compulsive condition most often precedes the onset of depression and there are strong

suggestions of genetic or biological links.

We can take a look at Berkowitz’ obsessive rituals, and Dahmer’s terror for the dreaded

event, but more importantly these personalities that follow their rules sound deadly

similar to the emotions of those whose main pathology stem from a need to dominate

and control, (Giannangelo,1993).

2.3.6. Post traumatic stress

According to Gianangelo (1996, the DSM-III, 1987), the opening statement regarding

this condition put it to a serial killer’s perspective: “The person experienced an event

outside the range of human experience and that would be markedly distressing to almost

anyone”. The DSM-IV goes on to note the essential range of human experience and that

of characteristic symptoms following exposure to an extreme traumatic stressor.

The person suffers a markedly reduced ability to feel emotions especially those

associated with intimacy, and he shows diminished responsiveness to the external

world, referred to as the ‘psychic numbing’ or emotional anesthesia, usually soon after a

traumatic event.

The childhood trauma that all serial killers seem to share, whether it is emotional,

physical, and sexual or a combination would most likely fit the description of a

distressing event, serious enough to cause these symptoms. Unfortunately this has not

been dealt with appropriately.

Table 2.3.6.

Diagnostic criteria for post traumatic stress disorder

A. The person has been exposed to a traumatic event in which both of the following

were present:

1. The person experienced, witnessed or was confronted with an event or events that

involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical

integrity of self or others.

48

2. The person’s response involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror. Note: In

children, this may be expressed instead by disorganized or agitated behaviour

B. The traumatic event is persistently re-experienced in one (or more) of the following

ways:

1.

Recurrent distressing recollections of the event, including images thoughts, or

perceptions. Note: In young children, repetitive play in which themes or aspects

of the trauma are expressed may occur.

2.

Recurrent distressing dreams of the event. Note: In children, there may be

frightening dreams without any recognizable content.

3.

Acting of felling as if the traumatic event were recurring (includes a sense of

reliving the experience, illusions, hallucinations and dissociative flashback

episodes, including those that occur on awakening or when intoxicated). Note: In

young children, trauma-specific re-enactment may occur.

4.

Intense psychological distress at exposure to internal or external cues that

symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event.

5.

Physiological reactivity on exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize or

resemble an aspect of the traumatic event.

C. Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma and numbing of general

responsiveness (not present before the trauma), as indicated by three of the

following:

1.

Efforts to avoid thoughts, feelings or conversations associated with trauma

2.

Efforts to avoid activities, places or people that arouse recollections of the trauma

3.

Inability to recall an important aspect of the trauma

4.

Markedly diminished interest or participation in significant activities

5.

Feeling of detachment or estrangement from others

6.

Restricted range of affect (e.g. unable to have loving feelings)

7.

Sense of foreshortened future (e.g. does not expect to have a career, marriage,

children or a normal life span)

D. Persistent symptoms of increased arousal (not present before the trauma), as

indicated by two (or more) of the following:

49

1.

Difficulty falling or staying asleep

2.

Irritability or outbursts of anger

3.

Difficulty concentrating

4.

Hypervigilance

5.

Exaggerated startled response

E. Duration of the disturbance (symptoms in Criteria B, C and D) is more than once (1)

month.

F. The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social,

occupational or other important areas of functioning.

Further criteria, not for the purpose of this section

(DSM -IV, 1994)

The dissociative response of Dahmer could certainly be interpreted as post-traumatic

response. Victims of post–traumatic stress often experience recurrent and intrusive

distress, as well as dreams, illusions, hallucinations, and (as discussed) dissociative

episodes.

Other symptoms relating to serial killers are feelings of detachment or

estrangement from others, the inability to have loving feelings, a sense of a

foreshortened future, irritability, outbursts of anger, and difficulty concentrating.

2.3.7. Delusional disorder

In reading through the material for this dissertation the presence of non-bizarre

delusions persists throughout the subjects’ lives, for example Ed Gein, who believed that

a relationship with a woman was a sin.

Table. 2.3.7.

Diagnostic criteria for Delusional Disorder

A. Non-bizarre delusions (i.e. involving situations that occur in real life, such as

being followed, poisoned, infected, loved at a distance, or deceived by a spouse

or lover, or having a disease) of a duration of at least one month.

50

B. Criterion A for Schizophrenia has never been met. Note: Tactile and olfactory

hallucinations may be present in the Delusional Disorder if they are related to the

delusional theme.

C. Apart from the impact of the delusion(s) or its ramifications, functioning is not

markedly and behaviour is not obviously odd and bizarre.

D. If mood episodes have occurred concurrently with delusions, their total duration

has been brief relative to the duration of the delusional periods.

E. The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g.

a drug of abuse, a medication) or a general medical condition.

Specify type (the following types are assigned, based on the predominant

delusional theme):

Erotomanic Type:

delusions that another person, usually of a higher status, is

in love with the individual

Grandiose Type:

delusions of inflated worth, power, knowledge, identity or

special relationship to a deity or famous person

Jealous Type:

delusions that the individual’s sexual partner is unfaithful

Persecutory Type:

delusions that the person (or someone to whom the person

is close) is being malevolently treated in some way

Somatic Type:

delusions that the person has some physical defect or

general medical condition

Mixed Type:

delusions characteristic of more than one of the above

types, but no one theme predominates

Unspecified Type

51

2.4. PSYCHOLOGICAL APPROACH

(Certain studies attempt to alleviate our “dumbfoundedness” where causes of behaviour,

as these being discussed are concerned.)

The importance of childhood for later adult development in both animals and humans

has been well documented (McElroy, 1978).

Chamove, Rosenblum and Harlow (1973) observe infant rhesus monkeys rose together,

without a mother figure, and compared their behaviour with other rhesus monkeys raised

with their mothers. It was found that mothers (with infants) would normally begin to

reject the infant’s clinging behaviour at about three months. By doing so, the mother

seemed to encourage the infant to start to explore the environment, rather than to

encourage further dependency. At the same time, those monkeys raised in the absence

of mothering demonstrated disturbed attachment behaviours. This study suggests the

importance of a consistent parent figure (mother in this case) in the development of

security that encourages social belonging.

At the other extreme, McElroy’s research (1978) has suggested that when mother-infant

attachments are too intense, which is to say that if dependency is continued for too long

both sexual and social development may be inhibited, as in the case of Ed Gein.

Primate studies thus suggest that serious disruption of normal mother-infant relationship

patterns can occur; either in the direction of too closes an attachment or too distant a

mother-infant relationship.

Bowlby (1980) has explored the impact of selected childhood experiences on

subsequent growth and development, including the impact of loss on the human child.

He postulates that during healthy development, the child develops affectional bonds with

the parents, a process known as “attachment behaviour”. This attachment behaviour is

achieved through consistency in parental-child interactions. As Bowlby (1980) notes,

however, the parents might engage in inconsistent parenting for a number of different

reasons. It is even possible that one or perhaps even both parents might leave the

child’s environment through illness, marital separation, divorce, death or abandonment.

He goes on to suggest that a neurotic and psychotic character might in some cases be

52

the result of mourning processes evoked during childhood having taken an unfavourable

course, thereby leaving the person prone to respond to later losses in a pathological

way.

Serial murderers are frequently found to have unusual or unnatural relationships wit h

their mothers. Lunde (in Leyton, 1986) notes, “Normally there is an intense relationship

with the mother. “Many serial murderers have had intense, smothering relationships with

their mothers – relationships filled with both abuse and sexual attraction” (“The Random

Killers”, Nov 26, 1984).

When looking at studies done on sadistic fantasy, sadistic behaviour and offending, we

can most certainly take the study that M.J. MacCulloch, P.R. Snowden, P.J.W. Wood

and H.E. Mills (1983) did, including sixteen male special hospital patients. They were

used because each had a diagnosis of a psychopathic disorder. This formed the basis

of the descriptive study. In only three cases were the crimes explicable in terms of

external circumstances and personality traits. The offences of the remaining 13 cases

became comprehensible only when the offender’s internal circumstances were explored.

The investigation revealed repetitive sadistic masturbatory fantasies that had spilled over

into overt behaviour because the patients had felt impelled to seek and create

increasingly dangerous in vivo ’try-outs ’ of their fantasies.

For the purpose of this dissertation, sadism is defined as the repeated practice of

behaviour and fantasy, which is characterized by a wish to control another person

through domination, denigration or inflicting pain, for the purpose of producing mental

pleasure and sexual arousal (whether or not accom panied by orgasm) in the sadist,

Leyton (1986).

The range of controlling behaviour under consideration forms a continuum from subtle

verbal control through various types of psychological control to actual physical

intervention such as bondage, imprisonment, hypnosis anesthesia and even blows to

render the victim unconscious or dead.

53

2.4.1. Dissociation

According to Giannangelo (1996), John and Helen Watkins have found the presence of

“ego states” in many people, which are more simply attitudes or moods. They postulated

that these ego states are personality systems that have split off from the main

personality. They found these fractioned personality states to be fairly common in many

people, to be somewhat independent from each other and to have a strong controlling

effect on the person.

The process of dissociation is a normal psychological process, which provides the

opportunity for a person to avoid, to some degree or other, the presence of memories

and feelings that are too painful to tolerate. Dissociation is a continuum of experiences

ranging from the process of blocking out events going on around us (such as when

watching a movie) to Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD) where personalities are

separate compartmentalized entities.

When a person is totally absorbed in a fantasy, he dissociates himself from everything

around him. Anger and emptiness become the energy and motivational forces behind

the fantasy, while in the fantasy the person experiences a sense of excitement and

relief.

This leads to a dual identity, one being that associated with reality and the people he

associates with every day (Carl Jung’s Persona) and the other the secret identity that is

able to manifest the power and control he would like over others (Carl Jung’s Shadow

concept). If the person is angry and bitter, this altered identity is usually an animal of

destruction, Giannangelo (1996).

As the person shifts back and forth between the two identities in his attempt to meet his

various needs, they both become an equal part of him, the opposing force being

suppressed when he is attempting to have his needs met through the person he has

created to satisfy his deepest hunger. This identity becomes stronger than the “good”

side, and the person begins to experience being possessed or controlled by this dark

side of him. This is partly because the dark side is the part anticipated to meet the

54

person’s strongest needs, and partly because the good side is the part that experiences

the guilt over the “evil” thoughts and therefore, out of necessity, is routinely suppressed.

Another phenomenon usually considered in the psychology of serial murder is the

dissociative state or disorder. Dissociation (Barlow and Durand, 1995) is the detachment

or loss of integration between identity or reality and conscienceness. In other words, it is

the mental ‘separation’ from the physical place of an individual. The phenomenon has

been used to describe people’s reactions to various traumatic experiences, as well as

precursor to pathologies described in the DSM-IV, such as fugues, amnesias,

depersonalization, and post-traumatic stress syndrome.

Causality regarding dissociative states includes severe childhood trauma and some

evidence of a physical predisposition. Many of those who experience dissociative states

are of above-average intelligence, another trait found in many serial killers.

Literature involving serial killers and the possible presence of a dissociative state is

extensive, e.g. about Jeffery Dahmer, Cavendish (1996) reported that he showed all

signs of chronic autism – the inability to notice other people or respond to them,

deadness in the eyes, lack of any natural smile, and apparently all-conquering selfsufficiency. (p.9)

These episodes indicate a certain level of the dissociative process, albeit on a minor

scale. Usually, the process does not appear as a full-blown dissociative disorder, such

as a psychogenic fugue state or a dissociative identity disorder and does not enter into

the psychopathology of the serial killer. At times these have been used by serial killers

as an attempt at malingering or as a basis for insanity defense, i.e. Gacy and Kenneth

Bianchi (The Hillside Strangler).

Drawing a parallel between a psychopathic personality and the dissociated demeanor of

the serial killer, Meloy (1992) noted that a psychopathy is, among other things, a

disorder of profound detachment.

55

He also added that from this conscienceless, detached psychology emerges a

heightened risk of violence, most notably a capacity for predation, i.e. one of the altars

may serve as a protector, thus becoming violent and dangerous.

Table 2.4.1

Diagnostic criteria for Dissociative Identity Disorder

a. The presence of two or more distinct identities or personality states (each with its

own relatively enduring pattern of perceiving, relating to, and thinking about, the

environment and the self).

b. At least two of these identities or personality states recurrently take control of the

person’s behaviour.

c. The inability to recall important personal information that is too extensive to be

explained by ordinary forgetfulness.

d. The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g.

blackouts on chaotic behaviour during alcohol intoxication) or a general medical

condition (e.g. complex partial seizures). Note: In children, the symptoms are not

attributed to imaginary playmates or other fantasy play.

The discussion of dissociation leads to the theory in the psychology of rationalizing

killing of doubling.

2.4.2. The creation of the shadow

The extreme enjoyment of fantasy is enhancing through a self-sustained hypnotic

trance, and it creates an appetite, which gets out of control. Ted Bundy, in telling

Michaud and Aynesworth (1989; In Hare, 1993) how a psychopath killer is created,

stated:

“There is some kind of weakness that gives rise to this individual’s interest in the kind of

sexual activity involving violence that would gradually begin to absorb some of his

56

fantasy…. Eventually the interest would become so demanding toward new material that

it would only be catered to by what he could find in the dirty book stores...”(p.68)

The offender may attempt to curb the problem that is developing. When this does not

work, he attempts to indulge in the fantasy rather than fight it to see if that would work.

Ultimately, when a person has visualized killing over and over again, a time may come

when an actual event, similar to what he has been fantasizing about, presents itself. At

such a time, under the right circumstances, the offender finds himself automatically

carrying out an act he has practiced so many, many times in his mind.

Finally,

inevitably, this force, this entity, makes a breakthrough. Bundy commented:

“The urge to do something to that person (a woman he saw) seized him - in a way he’d

never been affected before. And it seized him strongly. And to the point where, uh,

without giving a great deal of thought, he searched for some instrumentality to, uh, uh,

attack this woman…there was really no control at this point…”(pp.72-73)

The offender may partially, or completely, dissociate the crime. Following the event, the

offender’s mind returns to the realm of the real world and he often experiences surprise,

guilt and dismay that such an act could have happened.

By acting out the fantasy, the dark side or shadow now becomes a more permanent part

of the person’s personality structure.

Much like other theories, Robert Ressler, an FBI profiler, writes, “psychopaths… are

known for their ability to separate the personality who commits the crimes from their

more in-control selves” (1992).

They speak of the development of a ‘separate being’, living independently within one

that has preconsciously split off and has an independent existence with independent

motivation, separate agenda, etc. from which “evil, sadism, destructiveness or even

demonic possession” can emanate. He attributes this development to those elements of

the self that have been disavowed and artificially suppressed early in life. The causes of

dissociative disorders are not well understood but often seem to relate to traumatic

57

events and the tendency to escape psychologically from the experience or memories of

these traumatic events.

Physical transformation can take place during these switches. Posture, facial

expressions, patterns of facial wrinkling, and even physical disabilities may emerge

during a switch (Barlow and Durand, 1995).

According to Barlow and Durand (1995), the history of almost every patient presented

with this disorder contains horrible, often unspeakable examples of childhood abuse. Of

the 100 cases reviewed by Putnam et al, it was found that 97% of the patients had

experienced some significant trauma, usually sexual or physical abuse. Of the cases

that Rose et al (in Barlow and Durand, 1995) reviewed, 95% reported physical or sexual

abuse. This type of abuse is however not the only cause of trauma. These observations

have led to wide-ranging agreement that the cause of DID is rooted in a natural

tendency to escape or ‘dissociate” from the unremitting negative affect associated with

severe abuse.

The lack of social support during or after the abuse also seems implicated in etiology. As

with most psychopathology, the behaviour and emotions that make up disorders seem

rooted in otherwise normal tendencies present in all of us. Lifton also mentions that

doubling can include elements considered characteristic of sociopathic impairment, such

as disorder of feelings, pathological avoidance of a sense of guilt, and a resort to

violence to overcome a masked depression. Murderous behaviour may thereby cover a

feared disintegration of the self; a concept that appears so critical and so damaged in

the view of a serial killer.

He also mentions that response received from the mother is ‘taken in’ by the infant

whether it is praise or the induction of shame and this is then experienced as either pride

or guilt. These emotions are thus seen as psychological functions, which lie rooted in

the concrete, observable communication that makes up the mother-child relationship.

The self’s substance is thus the communication that causes interaction. This

communication is described by Kohut not only to be concrete but empathetic; these

interchanges thus form a significant part of the child’s burgeoning sense of self. This

58

basic infrastructure thus form s the basis for the child’s psychic infrastructure that affects

how the child interacts and relates to and with others later in life, and to him. Because

this relationship occupies so much of the child’s early life and so much emotional

gratification and deprivation is involved, object relations theory states that this forms the

basis of all subsequent relationships (Cashdon, 1988).

Even though all of the above-mentioned disorders have been documented, the

conclusions that have been reached are based on retrospective studies or correlations

rather than the prospective examination of people who may have undergone the severe

trauma that seems to lead to DID.

2.5. ETIOLOGY

2.5.1. Introduction

Ever since a mild-mannered motel keeper named Norman Bates became possessed by

the evil spirit of his dear, departed mother, people have associated serial killers with split

personalities. In reality, however, multiple personality disorder (or MPD, as it is known in

psychology) is an extremely rare condition. Still, it has not kept a whole string of serial

killers from trying to blame their crimes on their ostensible alter egos.

Likewise, John Wayne Gacy insisted that his thirty-three torture killings were actually the

work of an evil personality he called “Jack”.

Table 2.5.1

312.40 Homicidal Pattern Disorder

A.

Deliberate and purposeful murder or attempts at murder of strangers on more

than one occasion

B.

Tension or affective arousal at some time before the act

C.

Pleasure, gratification or relief in the commission or reflection of the acts

D.

Personality traits consistent with the diagnosis of at least one Cluster B

Personality Disorder (antisocial, borderline, historic, narcissistic).

E.

Understanding the illegality of actions and continuing to avoid apprehension

59

F.

Murders not motivated by monetary gain, to conceal criminal activity, to express

anger or vengeance, in response to a delusion or hallucination, or as a result of

impaired judgment (e.g. in dementia, mental retardation, substance intoxication)

Many individuals have difficult, even traumatic childhoods.

However, most do not

develop into serial killers. The continued stressors of social inadequacy and sexual

dysfunction serve only to exacerbate the situation. It follows that there must be an

additional element – a ticking bomb waiting to go off.

2.5.2. Developmental Background

2.5.2.1. Biological perspectives

Giannangelo (1996) mentions a study done by Lombroso, who observed the physical

correlations between violent (“born”) criminals and certain animals or “beasts of prey”.

His distinction between the “born criminal” and the “occasional criminal” marks the

predatory nature of the serial killer. According to Giannangelo (1996) confirming

evidence by Richard Dugdale was provided soon after Lombroso’s declarations

regarding the inherited nature of criminal tendencies.

Dugdale’s book included a study of a clan of two brothers who married their illegitimate

sisters ; their results showed that out of over seven hundred descendants, only six did

not become prostitutes or criminals. Henry Goddard, another sociologist, studied a

soldier who fathered a child with a “feeble-minded” girl and later married a Quaker of an

honest and intelligent family. About five hundred of the Quaker descendants were

traced, none of whom were criminals; of the same number of the “feeble-minded” girl,

only ten per cent were normal (Wilson, in Giannangelo, 1996). Growing research has

been indicating that aggressiveness and criminality do have a genetic factor.

Moyer (in Giannangelo, 1996) mentions that predatory behaviour of prey animals reflects

a neurological basis that is different from that of other kinds” of behavior.

The calm, purposeful behaviour of the serial killer can thus be compared to that of the

aggressive predator, rather than to the fight-stimulated organism.

60

(1) Xyy syndrome

Serial murder is such an overwhelmingly evil act that it is natural for people to wonder

“Why? Why would a human being commit such a monstrous crime?”

There is a

desperate need to find an explanation that would make sense of this incomprehensible

horror. Schechter and Everitt (1996) states that for at least a hundred years, scientists

have been searching for a single, identifiable cause for criminal violence. In 1968, they

finally came up with one. The answer to the question why? turned out to be Y.

More precisely, it turned out to be a Y chromosome. As everyone who has taken high

school biology know s, there are two sex chromosomes, X (female) and Y (male). Every

cell in the average man contains one of each. A few men, however, have and extra Y,

or male, chromosome – a condition known as the XYY Syndrome.

Once they made this discovery, scientists began theorizing that this extra dash of

maleness made its possessor even more masculine – i.e. crude, aggressive and violent

– than normal.

(2) Head Injuries

Another so-called answer has been found in head injuries.

Some specialists put the blame on “juvenile cerebral trauma” – or, in plain English, being

hit on the head as a child. The brain damage done by such an injury can, according to

these experts, turn people into serial killers. Some of the head-battered psychos include

some of the most infamous names in the history of serial murder – John Wayne Gacy,

Richard Speck, Charles Manson and Henry Lucas, Schechter and Everitt (1996)

Unfortunately, the cerebral trauma theory of serial murder has the same limitations as

other reductive explanations.

Head injuries are an everyday fact of childhood life.

Millions of children fall off bikes and swings and land on their heads, and only a small

fraction turns out to be psychopathic killers. On the other hand, not all serial killers

sustained head injuries. However, a head injury combined with other predisposing

factors may well contribute to incipient psychopathology.

Mark (with Southgate and

61

Ervin, separately), according to Gianangelo (1996) undertook much research on the link

between head trauma and violence and,), has found that head trauma may cause

aggressive outbursts, particularly when the temporal lobe is involved, but this seems to

be a rare occurrence. It was also found that there is a relationship between the eruption

of homicidal violence and a tumor of the limbic system: in the cases reported, the

violence ceased when the tumor was removed.

2.5.2.2. Environmental factors

Deserving equal consideration as biological factors are environmental factors. Not all

instances of negative environmental settings are dramatic, but they are certainly

abhorrent enough to cause serious damage to a person’s sense of self or to the

development of an appreciation of the lives of others. The severe beatings John Wayne

Gacy received from his father, for his suspected homosexuality and underachievement

or the constant inprintment of religiosity of Ed Gein’s mother are just two examples

(Cahill, 1987; Schechter, 1989).

The combination of physical predisposition and environmental stresses helps develop a

pattern of maladjustment with two major consequences: a distorted sense of self and a

dysfunctional sexual component, discussed later in this chapter.

(1) Family circumstances

According to Schechter and Everitt (1996), the domestic setting in which they grow up is

also typical of most criminals. In a quarter of the cases, it was known that the offender’s

immediate family had a history of criminality. Their families were typically dysfunctional

in a variety of recognizable ways: an absent father (65%), frequent moves (45%),

institutionalized (41%), a mother known for per promiscuity (38%), and much violence in

the family (50%).

These experiences left a sizable minority of these men physically handicapped (18%),

scattered (14%) or with a stutter or similar disorder (13%). Indeed, as has been noted

for many sub-groups who are involved in violent crime, a high proportion (45%) had

suffered some serious head injury or other physical trauma at some point in their life

prior to killing. This seems to reflect their lifestyles rather than being a distinct cause of

62

their crimes.

They relate to the high proportion (63%) that had been physically or

sexually abused during their childhood, many by family members (48%) (Schechter and

Everitt, 1996).

In the 1985 FBI study of sexually oriented murders (FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin),

family histories were found to consistently lack a process for the subjects, as children, to

become adults and relate to and value other members of society. Inadequate patterns

of relating as well as infrequent positive interaction with family members were noted. A

high degree of instability in the home life, as well as a poor-quality attachment among

family members, was also found. Interviews also showed that most offenders had

unsatisfactory relationships with their fathers, while reporting that the relationships with

their mothers were of a “highly ambivalent quality.”

(2) Abuse and neglect

Abuse from a parent or other caretaker must be one of the most hurtful of all insults,

because it combines physical pain with the psychological blow of being attacked by

one’s protector. The child has no way of judging the meaning of what is happening. His

or her perspective of adult behaviour towards children is limited, and it is easy to believe

that all parents severely spank, beat or do other violence to their offspring. Or the child

may justify the abusing parent’s behaviour by assuming the guilt of being bad and

therefore deserving of the blows. Whatever his or her beliefs or feelings, the child’s

inferior states vis-à-vis the parent gives rise to a feeling of impotence to change the

situation. Thus, the boy or girl grows up not only risking physical damage but also

holding a distorted view of the parent-child relationships, including a first-hand lesson in

aggression between family members (Pelton, 1981).

(2a) Child abuse

Although extreme violence towards children is extensively publicized, many incidents of

child physical abuse involve minor injury, and are impulsive acts occurring during

unsuccessful attempts at discipline (Wolfe, 1987). These typically reflect the progressive

development of aversive parent–child exchanges.

For example, inconsistent

punishment of a child will result in a parent’s capacity to control behaviour through

63

positive reinforcement. Under such conditions, attempts at discipline involve punitive

tactics of accelerating intensity and an increased likelihood of escalation to violence

(Patterson, 1982). Possible casual factors in abuse therefore include characteristics of

parent and child, the history of their interaction, adverse family conditions exacerbating

aversive interactions, and social and cultural factors supporting punitive discipline.

A child’s characteristics may increase the risk of abuse by imposing stress on the parent,

or by eliciting parental rejection, and unskilled mothers can be “trained” by their children

to use aversive discipline (Patterson, 1982).

Psychological research on child abuse has drawn on psychodynamic and social learning

models, and these approaches have also guided attempts to identify the effect abuse

has on the victims. They suggested that the more prominent effects were interpersonal

ambivalence and hypervigilance regarding the behaviour of others, disturbed selfconcept and superego development, and delays in the development of speech,

language, and motor functions. While these are common findings, no uniform pattern of

psychological problems has been identified (Wolfe, 1987).

There is thus only modest support for the “cycle of violence” hypothesis and many

mediating factors determine whether or not an abused child becomes an abuser or a

violent delinquent.

Child abuse has “internalizing” consequences such as depression

and lowered self-esteem, as well as “externalizing” effects in the form of aggression.

The aspects of the abused child’s environment, which are psychologically most

damaging, are also uncertain.

While it is assumed that major effects result from

maltreatment by a caretaker on whom the child depends and looks to as a model, other

significant sources of impaired child development include witnessing violence between

family members (Wolfe, 1987), and the social consequences of the labeling of a family

as abusive.

(3) Esteem development and sense of self

There is a wide variety of different descriptions and definitions when attempting to define

what self-esteem is. What is found, however, is that a person’s self-esteem does appear

to begin to grow and develop as soon as he or she begins to experience a sense of self

64

as an individual? The particular childhood we experience is important; because it is then

that our basic personality traits and habits are formed.

According to Lindenfield (1995), the following play an important role in decreasing a

child’s self-esteem:

1. Not having their basic needs adequately met – especially when others are noticed to

receive more or better

2. Having their feelings persistently ignored or denied

3. Being put down, ridiculed or humiliated – especially for just being you or just acting

your age

4. Being required to assume a ‘false self’ in order to impress others or get their needs

met

5. Being forced to engage in unsuitable activities

6. Being compared unfavourably to others

7. Being given the impression that their views or opinions are insignificant – especially

in matters concerning them

8. Being deprived of a reasonable explanation – especially when others are better

informed

9. Being given a label that devalues their individuality

10. Being over-protected

11. Over-punishing

12. Being given too few rules and guidelines

13. Being on the receiving end of inconsistent behaviour – especially if this is in the

parent-child relationship

65

14. Being threatened with receiving physical violence – especially if they are told that

they have driven the perpetrator to this immoral and undesirable act

15. Being subjected to inappropriate sexual innuendo or contact – especially from a

person who is entrusted to care for them

16. Being blamed for leading a loved and respected person astray

17. Being over-fed a diet of unachievable ideas by the media – especially if they are

disadvantaged in any way

(pp.11-13)

The one component that seems to play a role in most serial killers’ childhoods is the

‘emotional rape’ that most have experienced, besides the physical or sexual abuse they

have suffered. According to Blackburn (1993), this injury prohibits them from developing

a healthy sense of self, an understanding of intimacy, or of feelings of personal selfesteem. It is speculated that childhood is when these killers develop their obsessive and

distorted view of their own identities and their ever-increasing need for control. Most

have had little or no control over them and their surroundings as children, and their

resulting fear in relation to control issues are understandable if not predictable.

Many of the personality disorders discussed above involve a sense of self and a lack of

control, but these also overlap with many other issues such as, rejection, overreaction to

stress, misuse of alcohol and other substances, and fear of loneliness.

(4) Sexual component

A consistent factor in the development of a serial killer is the presence of a seriously

dysfunctional sexual disorientation or deviance. Many researchers see this as important,

eventhough the importance may vary in degree. Some feel that it is a key influence while

others view it as merely incidental. The position I take is that deviant sexual motivation

has an impact on the killer’s psychology that it is the clearest link between mental and

physical processes in the psychopathology in question.

66

Of importance to this section is the relationship between mother and child, this has

however, already been discussed above. Homosexuality and issues of gender are

considered causes for concern when they cause the individual persistent or marked

distress about his or her sexual orientation or “other traits related to self-imposed

standards of masculinity or femininity” (DSM-IV, 1994.) Killers who are fue lled by rage or

a hatred of their own sexuality include sexually inadequate or homosexual individuals

such as John Wayne Gacy, and possibly Jeffrey Dahmer. They are prime examples of

violent expression of frustration and rage. Storr (1972) states that the partial explanation

he can give to the origin of deviation is that most seeds are sown in the early stages of

life, and that the failure to reach sexual maturity can be understood in terms of the

difficulties in the changing relation between parents and child. Storr is also of the view

that sexual deviations are chiefly the result of persistence of childhood feelings of guilt

and sexual inferiority. Confidence that one is, or can be, lovable is more essential than

assurance in one’s physical appeal. Although a high degree of physical attractiveness

may lead to a succession of partners, it does not enable a man or woman to sustain a

relationship unless it is supported by an underlying conviction of being valuable as a

person.

This conviction of sexual inferiority regularly found among sexual deviants seems to

have two roots. One, a generalized feeling of being unlovable or unacceptable, which

may often be attributed to an earlier failure in the relationship between mother and child.

The second being more specifically the inability to identify with the current role assigned

to a male or female by society.

As mentioned, guilt seems to form an integral part of the origin of sexual deviation.

Looking at our own lives , we see how our parents’ attitudes towards sex have powerfully

guided our acceptance or rejection of our own developing erotic feelings; thus, there is

no denying the powerful effec t of this.

Every child gradually learns what pleases and displeases his or her parents, and since it

is the normal household, that gives a child his sense of well-being and security, he soon

learns to comply with the parents’ wishes insofar as his instinctive nature permits. The

mere absence of positive approval is for a sensitive child enough to label the subject as

‘bad’ and to create a sense of guilt about it. For example, Ed Gein’s mother taught him

67

from a young age that sex was dirty and all women were of a dirty nature. Thus the

internal struggle between his desires and his mother’s beliefs ensued.

In any ‘normal’ family some extent of guilt does exist, as a child’s sexuality cannot be

fully expressed within the family circle, and he or she is to remain secretive.

The child thus has these powerful impulses within, which cannot be brought into relation

with those on whom he is dependent. It is seemingly more difficult to escape from

parents who appear to have been loving and kind than those who have been crudely

moralistic.

(5) Fantasy

A deviant and consuming fantasy appears to be the fuel that fires the process. Serial

killers seem, at an early age, to become immersed in a deep state of fantasy, often

losing track of the boundaries between fantasy and reality. They dream of dominance,

control, sexual conquest, violence and eventually murder.

According to Giannangelo (1996), Burgess, Hartman and Ressler found a fantasy-based

motivational model for sexual homicide. Interactive components included impaired

development or attachments in early life; formative traumatic events; patterned

responses that serve to generate fantasies; a private, internal world consumed with

violent thoughts that leave the person isolated and preoccupied; and a feedback filter

sustaining repetitive thinking patterns. In this study, they found evidence of daydreaming

and compulsive masturbation in over 80 per cent of the sample, in both childhood and

adulthood. Fantasy’s role in the serial murderer’s life is providing “an avenue of escape

from a world of hate and rejection”.

Schechter and Everitt (1996) say that, though we are sometimes loath to admit it (even

to ourselves) everyone harbors socially unacceptable thoughts – forbidden dreams of

sex and violence. There si a big difference, though, between the fantasies of serial

killers and those of ordinary people. For one thing, the former is a whole lot sicker. An

average guy might imagine himself making love to a super model. The serial killer, on

the other hand, will think obsessively about shackling her to a wall, then slicing up her

body with a hunting knife. There is a second, even scarier difference: unlike a normal

68

person (who might indulge in an occasional daydream), serial killers are not satisfied

with thinking about taboo behaviour. They are compelled to act out their fantasies – to

turn their darkest imaginings into real-life horrors.

It appears that many serial killers often retreat into their world of fantasy at some point in

their developing pathology. They may delve into sexual, violent, graphic scenarios and

use pornography or detective magazines to assist their creative process. Linked with

continued masturbation, retreating within themselves and self-imposed isolation, they

begin down the path of a murderous obsession. Fantasy is also a logical first step

towards a dissociative state, a process that allows the serial killer to leave his stream of

consciousness for what is, to him, a better place.

People who grow up to be serial killers begin indulging in fantasies of sadistic activity at

a disturbingly young age – sometimes as early as seven or eight. While their peers are

pretending to be sports stars or super heroes, these incipient psychopaths are already

daydreaming about murder and mayhem. Interviewed in prison after his arrest, one

serial killer explained that as a child he spent so much time daydreaming in class that his

teachers always noted it on his report cards. “And what did you daydream about?”

asked the interviewer. His answer: “Wiping out the whole school”.

Another serial killer recalled that his favourite make-believe game as a little boy was

“gas chamber” in which he pretended to be a condemned prisoner undergoing an

agonizing execution. Fantasizing about a slow, painful death was a source of intense

boyhood pleasure to this budding psycho.

Unlike other people, the serial killer never outgrows his childhood fantasies. On the

contrary: cut off from normal human relationships, he sinks deeper and deeper into his

private world of grotesque imaginings. From the outside, he might appear perfectly well

adjusted – a hard worker, good neighbour, and all-around solid citizen.

But all the while, bizarre, blood-drenched dreams are running rampant inside his head.

Since psychopaths lack the inner restraints that prevent normal people from acting out

their hidden desires, there is nothing to keep a serial killer from trying to make his

darkest dreams come true. Eventually, this is exactly what happens. His perverted

69

fantasies of dominance, degradation and torture become the fuel that sets his crimes in

motion. For this reason, former FBI agent Robert K Ressler – the man who coined the

term “serial killer” – insists that it is not child abuse or early trauma that turns people into

serial killers. It is their dreams.

As Ressler puts is, creatures like Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy and the like are

“motivated to murder by their fantasies”.

Fantasy can also be seen as a reason that the serial killer can calmly and methodically

dehumanize his victims.

He then reconnects with the real world (Bundy’s live-in

girlfriend referred to his “using me to touch base with reality”) and carries on immediately

after the crime with such seemingly mundane activities as going out for hamburgers

(Kendall, 1981).

Burgess et al. (in Leyton, 1999) reported a fantasy-based motivational model for sexual

homicide. The model, which has five interactive components, impaired development of

attachments in early life; formative traumatic events; patterned responses that serve to

generate fantasies; a private, internal world that is consumed with violent thoughts and

leaves the person isolated and self-preoccupied; and a feedback filter that sustains

repetitive thinking patterns. This was tested on a sample of 36 sexual murderers. In that

initial study, Burgess et al. found evidence for daydreaming and compulsive

masturbation in over 80% of the sample in both childhood and adulthood.

Violent fantasy was present in 86% of the multiple (or serial) murderers and only 23% of

the single murderers, suggesting a possible functional relationship between fantasy and

a repetitive functional relationship between fantasy and repetitive assaultive behaviour.

Even though the function of fantasy is speculative, Burgess et al. (1986) concurred with

MacCulloch et al. (1983) that once the restraints inhibiting the acting out of the fantasy

are no longer present, the individual is likely to engage in a series of progressively more

accurate “trial runs” in an attempt to enact the fantasy as it is imagined.

Consistent with this notion was the finding that at least three social learning variables

may be important in linking sexual arousal to deviant fantasy:

1.

Parental modeling of deviant behaviour in a blatant or attenuated fashion

70

2.

Repeated associations between the modeled deviant behaviour and a strong

positive affective response from the child

3.

Reinforcement of the child’s deviant response.

While it is unlikely that the translation of the fantasy into reality conforms precisely to a

classical conditioning model, it does appear that the more the fantasy is rehearsed, the

more power it acquires and the stronger the association between the fantasy content

and sexual arousal. Indeed, the selective reinforcement of deviant fantasies through

paired association with masturbation over a protracted period may help to explain not

only the power of the fantasies but also why they are so refractory to extinction.

(6) Animal torture

Childhood cruelty toward small, living c reatures is not necessarily a sign of

psychopathology. Lots of little boys who enjoy pulling the wings off flies grow up to be

lawyers or dentists. The sadistic behaviour of budding serial killers is something else

entirely. After all, it is one thing to chop an earthworm in two because you want to watch

the separate halves squirm; it is quite another to eviscerate you neighbour’s pet kitten

because you enjoy listening to its agonizing howls, Giannangelo (1996).

The case histories of serial killers are rife with instances of juvenile animal torture. As a

boy, for example, Henry Lee Lucas enjoyed trapping small animals, torturing them to

death, and then having sex with the remains. The earliest sexual activity of the appalling

Peter Kurten – the “Monster of Dusseldorf” – also combined sadism with bestiality. At

thirteen, Kurten discovered the pleasures of stabbing sheep to death while having

intercourse with them.

Instead of more conventional items, like baseball cards and comic books, little Jeffrey

Dahmer collected roadkill (Cavendish, 1996).

According to neighbours, he also liked to nail bullfrogs to trees and cut open live fish to

see how their innards worked. One of the favourite childhood pastimes of Moors

Murders Ian Brady was tossing alley cats out of apartment windows and watching them

splat on the pavement. Cats seem to be a favourite target of youthful sociopaths.

71

Edmund Kemper was only ten when he buried the family cat alive, then dug up the

corpse and decapitated it. Former FBI Special Agent Robert K Ressler mentioned one

sadistic murderer who was nicknamed “Doc” as a child because he liked to slit open the

stomachs of cats and see how far they could run before they died (Schechter and

Everitt, 1996).

Animal torture is, in fact, such a common denominator in the childhood of serial killers

that it is considered one of the three major warning signals of future psychopathic

behaviour, along with unnaturally prolonged bed-wetting and juvenile pyromania. The

vast majority of little boys who get their kicks from dismembering daddy longlegs or

dropping firecrackers into anthills lose their stomach for sadism at an early age. The

case is very different with incipient serial killers. Fixated at a shockingly primitive stage

of emotional development, they never lose their craving for cruelty and domination; quite

the contrary it continues to grow in them like a cancer. Eventually – when dogs, cats

and other small, four-legged creatures can no longer satisfy it – they turn their terrifying

attentions to a larger, two-legged breed: human beings (Giannangelo, 1996).

(7) Lesser crimes

‘Young’ serial killers commit many lesser crimes during their cooling-off periods or as a

forerunner to their killing. Ted Bundy, Jeffery Dahmer and others have worked their way

up the ladder to habitual homicidal acts, by committing arson, burglaries and acts of

molestation, obscene letter writing, assaults and much more.

According to Giannangelo (1996), these lesser crimes are of great importance as they

are usually sexual in nature. These acts represent sexual gratification and control, even

though they are on a smaller scale, and they reflect the basic motivations of a serial

killer. Many of these lesser crimes are committed with no motivation other than sexual

gratification and seizing control.

(8) Control

Among all the factors that seem to run across the board of serial killers’ profiles, one that

prominently stands out is control. Control is seemingly the underlying motivation for the

personality types mentioned previously. Killers seem to work towards the satisfaction of

72

their need for complete control, whether it is to build a fragile ego or to demonstrate how

weak everyone else is.

When looking for earlier signs of searching for control, we find many cases of enuresis

(bed-wetting) in the past of killers. Giannangelo (1996) quotes Dr J. Michaels, a pioneer

in the analysis of the correlation between enuresis and murderous behaviour:

“Persistently enuretic individuals are impelled to act. They feel the urgency of the

moment psychologically, as at an earlier stage they could not hold their urine” (p. 35). It

seems that the biological implications of lack of impulse control, plus repeated incidence

of such “poor impulse control” reflect this position.

Furthermore we find the prevalence of animal abuse, which also appears to be a

combination of sadistic or sexual urges and control or dominance needs.

The third leg of this triad of early crimes includes arson. Arson is said to have distinct

sexual features and represents the action of taking control of the situation, both in fire

setting and in pulling false alarms.

Control issues seem to be the underlying motivation for the personality types that were

discussed, the anti-social personality, the psychopath, the borderline as well as the

narcissistic. They all crave control, whether it is to build a fragile ego or to demonstrate

how weak everyone else is. Even necrophilia’s, according to Meloy (1992), acknowledge

the importance of control.

In necrophilia, total acceptance of the subject and the completely unconditional positive

regard and total acceptance are the ultimate control. Doctor Ashok Bedi examined

Jeffery Dahmer and agreed with this connection between necrophilia and control. In

Dahmer’s case he commented:

“His personality disorder, the alcohol addiction, the pedophilia, the necrophilia, his ego

and homosexuality, all were layers of his dysfunction. The preoccupation of having sex

with the dead person had to do with his feelings at different points in time. A living

person could not fill his need. Only a dead person, where he was totally in control and

73

there was no way of retaliation, belittlement, negation or abandonment” (Giannangelo:

43)

It seemed not so much being sadistic as wanting to be in control. Then it became a

question of what he was looking for – nurturing, wanting to be fed, that sort of thing. If

there was a need to show anger, then he might use anal sex. It depended on what his

needs were in his head at the moment.

When considering the issues of control and sadism, J.A. Apsche (in Giannangelo, 1996)

noted:

When, in children, control is substituted for intimacy (as manipulation and control

substituted for closeness), the child mistakenly learns that control is a substitute for

intimacy. For the sexual sadist, there is a need to take control to demonstrate power

and virility.

The mode of death selected si one that indicates that the victim had

meaning for the killer, and that the intimacy in the murderous act is part of the close

bond between the murderer and the victim formed in the killer’s fantasies and delusions.

(9) Religiosity

There are many people who blame our country’s social ills – including our epidemic of

violence crime – on the loss of old-fashioned religious values, as if the murder rate

would miraculously decline if South Africans spent fewer hours in front of the TV and

more time studying the Bible. Unfortunately, there is a slight problem with this theory.

Some of the most monstrous killers we have in our history were religious fanatics who

could recite scripture from memory and when they were not busy torturing children or

mutilating corpses they loved to do nothing better than read the Good Book (Schechter

and Everitt 1996).

Albert Fish, the cannibalistic monster who spent a lifetime preying on little children, is a

good enough example of this. From his earliest years, Schechter and Everitt (1996)

states was Fish fascinated with the Bible and at one point actually dreamed of becoming

a minister. As he grew older, his religious interest blossomed into a fully-fledged mania.

Obsessed with the story of Abraham and Isaac, he became convinced that he, too,

should sacrifice a young child - an atrocity he carried out on more than one occasion.

74

From time to time, he heard strange, archaic-sounding words – correcteth, delighteth,

chastiseth – that he interpreted as divine commandments to torment and kill.

He would organize these words into quasi-Biblical messages: “Blessed is the man who

correcteth his son in whom he delighteth with stripes”; “Happy is he that taketh thy little

ones and dasheth their heads against the stones”. Fish not only tortured and killed

children in response to these delusions but also subjected himself to a variety of

masochistic torments in atonement for his sins. One of his favourite forms of selfmortification was to shove sewing needles so deeply in his groin that they remained

embedded around his bladder. For the hopelessly demented Fish, his ultimate crime –

the murder, dismemberment and cannibalization of a twelve-year-old girl – also had

religious overtones.

As he told the psychiatrist who examined him in prison, he

associated the eating of the child’s flesh and the drinking of her blood with the “idea of

Holy Communion” (Schechter, 1990).

“And I will cause them to eat the flesh of their sons and the flesh of their daughters, and

they shall eat every one the flesh of his friend in the siege and straitness, wherewith their

enemies. And they that seek their lives shall straiten them”. Jeremiah, 19:9 (Albert