The Zoot-Suit and Style Warfare

advertisement

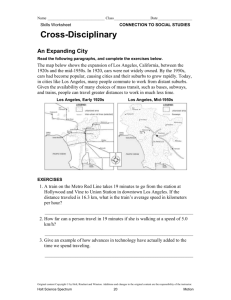

The Zoot-Suit and Style Warfare Author(s): Stuart Cosgrove Source: History Workshop, No. 18 (Autumn, 1984), pp. 77-91 Published by: Oxford University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4288588 Accessed: 04/02/2010 17:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=oup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History Workshop. http://www.jstor.org The Zoot-Suit and Style Warfare by Stuart Cosgrove INTRODUCIION: THE SILENT NOISE OF SINISTER CLOWNS What about those fellows waiting still and silent thereon the platform,so still and silent they clash with the crowd in theirvery immobility,standingnoisy in theirverysilence;harshas a cryof terror in their quietness? What about these threeboys, coming now along the platform, tall and sknder, walking with swingingshouldersin theirwell-pressed, too-hot-for-summersuits, their collars high and tight about their necks, their identicalhatsof blackcheapfelt set upon the crowns of their heads with a severe formality above their conked hair? It was as though Id never seen their like before: walkingslowly, their shoulders swaying, their legs swingingfrom their hips in trousersthat ballooned upward from cuffs fitting snug about their ankles; their coats long and hip-tight withshouldersfar too broad to be those of natural westernmen. Thesefellows whose bodiesseemed- whathad one of my teacherssaid of me? - 'You'relike one of those African sculptures, distortedin the interestof design.' Well, whatdesignand whose?' The zoot-suit is more than an exaggerated costume, more than a sartorial statement,it is the bearerof a complex and contradictoryhistory. When the nameless narratorof Ellison's Invisibk Man confrontedthe subversivesight of three young and extravagantlydressed blacks, his reaction was one of fascination not of fear. These youths were not simply grotesque dandies parading the city's secret underworld,they were 'the stewardsof somethinguncomfortClyde Duncan, a bus-boyfrom Gainesville,Georgia, appearedon the front page of the New York Timesat the height of the zoot-suitriots. 78 History WorkshopJournal able'2, a spectacularreminderthat the social order had failed to contain their energy and difference. The zoot-suit was more than the drape-shapeof 1940s fashion, more than a colourful stage-prophanging from the shoulders of Cab Calloway, it was, in the most direct and obvious ways, an emblem of ethnicity and a way of negotiatingan identiy. The zoot-suit was a refusal: a subcultural gesturethat refusedto concede to the mannersof subservience.By the late 1930s, the term 'zoot' was in commoncirculationwithinurbanjazz culture. Zoot meant something worn or performed in an extravagantstyle, and since many young blacks wore suits with outrageouslypadded shoulders and trousers that were fiercelytaperedat the ankles,the termzoot-suitpassedinto everydayusage. In the sub-culturalworld of Harlem'snightlife,the languageof rhymingslang succinctly described the zoot-suit's unmistakablestyle: 'a killer-dillercoat with a drapeshape, reat-pleatsand shoulderspadded like a lunatic'scell'. The study of the relationshipsbetweenfashionand social actionis notoriouslyunderdeveloped,but there is every indicationthat the zoot-suitriots that eruptedin the United States in the summerof 1943 had a profoundeffect on a whole generationof socially disadvantagedyouths. It was during his period as a young zoot-suiter that the Chicano union activist Cesar Chavez first came into contact with community politics, and it was throughthe experiencesof participatingin zoot-suit riots in Harlemthat the young pimp 'Detroit Red' began a politicaleducationthat transformed him into the Black radical leader Malcolm X. Although the zoot-suit occupies an almost mythicalplace within the historyof jazz music, its social and politicalimportancehas been virtuallyignored. There can be no certaintyabout when, where or why the zoot-suitcame into existence, but what is certainis that duringthe summermonthsof 1943'the killer-dillercoat' was the uniformof young rioters and the symbol of a moral panic about juvenile delinquencythat was to intensifyin the post-warperiod. At the height of the Los Angeles riots of June 1943, the New York Times carrieda front page articlewhich claimedwithoutreservationthat the firstzootsuit had been purchasedby a black bus worker, Clyde Duncan, from a tailor's shop in Gainesville, Georgia.3Allegedly, Duncan had been inspiredby the film 'Gone with the Wind'and had set out to look like Rhett Butler. This explanation clearlyfound favourthroughoutthe USA. The nationalpressforwardedcountless others. Some reportsclaimedthat the zoot-suitwas an inventionof Harlemnight life, others suggested it grew out of jazz culture and the exhibitionist stagecostumpsof the band leaders, and some argued that the zoot-suit was derived from militaryuniformsand importedfrom Britain. The alternativeand independent press, particularlyCrisisand Negro Quarterly,more convincinglyarguedthat the zoot-suitwas the productof a particularsocial context.4They emphasisedthe importanceof Mexican-Americanyouths, or pachucos, in the emergenceof zootsuit style and, in tentativeways, tried to relate their appearanceon the streets to the concept of pachuquismo. In his pioneering book, The Labyrinthof Solitude, the Mexican poet and social commentatorOctavio Paz throws imaginativelight on pachuco style and indirectlyestablishesa frameworkwithinwhich the zoot-suit can be understood. Paz's study of the Mexicannationalconsciousnessexaminesthe changesbrought about by the movementof labour, particularlythe generationsof Mexicanswho migratednorthwardsto the USA. This movement, and the new economic and The Zoot-suitand Style Warfare 79 social patternsit implies, has, accordingto Paz, forcedyoung Mexican-Americans into an ambivalentexperiencebetween two cultures. What distinguishesthem, I think, is their furtive, restless air: they act like personswho are wearingdisguises,who are afraidof a stranger'slook because it could strip them and leave them stark naked. . . . This spiritual condition, or lack of a spirit, has given birth to a type known as the pachuco. The pachucosare youths, for the most part of Mexicanorigin,who form gangs in southerncities; they can be identifiedby theirlanguageand behaviouras well as by the clothingthey affect.They are instinctiverebels, and NorthAmerican racismhas vented its wrath on them more than once. But the pachucosdo not attemptto vindicatetheir race or the nationalityof their forebears.Their attitudereveals an obstinate, almostfanaticalwill-to-be,but this will affirms nothing specific except their determination . . . not to be like those around them.5 Pachucoyouth embodiedall the characteristicsof secondgenerationworking-class immigrants.In the most obvious ways they had been strippedof their customs, beliefs and language.The pachucoswere a disinheritedgenerationwithina disadvantagedsector of North Americansociety; and predictablytheir experiencesin education, welfare and employmentalienatedthem from the aspirationsof their parents and the dominant assumptionsof the society in which they lived. The pachuco subculturewas defined not only by ostentatiousfashion, but by petty crime,delinquencyand drug-taking.Ratherthandisguisetheiralienationor efface their hostilityto the dominantsociety, the pachucosadoptedan arrogantposture. They flauntedtheir difference,and the zoot-suitbecame the means by whichthat differencewas announced.Those 'impassiveand sinisterclowns' whose purpose was 'to cause terrorinsteadof laughter,'6invited the kind of attentionthat led to both prestige and persecution.For Octavio Paz the pachuco's appropriationof the zoot-suitwas an admissionof the ambivalentplace he occupied. 'It is the only way he can establisha more vital relationshipwith the society he is antagonising. As a victim he can occupy a place in the world that previouslyignoredhim; as a delinquent,he can become one of its wicked heroes.'7The zoot-suitriots of 1943 encapsulatedthis paradox.They emergedout of the dialecticsof delinquencyand persecution,duringa period in whichAmericansociety was undergoingprofound structuralchange. The majorsocial change broughtabout by the United States'involvementin the war was the recruitmentto the armedforces of over four millionciviliansand the entranceof over five millionwomen into the war-timelabourforce. The rapid increase in militaryrecruitmentand the radical shift in the compositionof the labourforce led in turnto changesin familylife, particularlythe erosionof parental control and authority. The large scale and prolonged separationof millions of familiesprecipitatedan unprecedentedincreasein the rate of juvenile crime and delinquency.By the summerof 1943it was commonplacefor teenagersto be left to their own initiativeswhilst their parentswere either on active militaryservice or involved in war work. The increase in night work compoundedthe problem. With their parents or guardiansworkingunsocial hours, it became possible for many more young people to gather late into the night at major urbancentres or simplyon the street corners. 80 History WorkshopJournal The rate of social mobilityintensifiedduringthe period of the zoot-suitriots. With over 15 million civilians and 12 million militarypersonnel on the move throughoutthe country, there was a correspondingincrease in vagrancy.Petty crimesbecame more difficultto detect and control;itinerantsbecameincreasingly common, and social transienceput unforeseenpressureon housing and welfare. The new patternsof social mobilityalso led to congestionin militaryand industrial areas. Significantly,it was the overcrowdedmilitarytowns along the Pacificcoast and the industrial conurbationsof Detroit, Pittsburghand Los Angeles that witnessedthe most violent outbreaksof zoot-suitrioting.8 'Delinquency'emerged from the dictionaryof new sociology to become an everyday term, as wartime statistics revealed these new patterns of adolescent behaviour.The pachucosof the Los Angeles area were particularlyvulnerableto the effects of war. Being neither Mexicannor American, the pachucos, like the blackyouthswith whom they sharedthe zoot-suitstyle, simplydid not fit. In their own terms they were '24-hourorphans',having rejected the ideologies of their migrantparents.As the war furtheredthe dislocationof familyrelationships,the pachucos gravitatedaway from the home to the only place where their statuswas visible, the streets and bars of the towns and cities. But if the pachucos laid themselves open to a life of delinquencyand detention, they also assertedtheir distinctidentity, with their own style of dress, their own way of life and a shared set of experiences. THE ZOOT-SUITRIOTS:LIBERTY, DISORDER AND THE FORBIDDEN The zoot-suit riots sharply revealed a polarizationbetween two youth groups withinwartimesociety:the gangsof predominantlyblackand Mexicanyouthswho were at the forefront of the zoot-suit subculture,and the predominantlywhite Americanservicemenstationed along the Pacificcoast. The riots invariablyhad racial and social resonancesbut the primaryissue seems to have been patriotism and attitudes to the war. With the entry of the United States into the war in December 1941, the nation had to come to termswith the restrictionsof rationing and the prospects of conscription.In March 1942, the War ProductionBoard's first rationingact had a direct effect on the manufactureof suits and all clothing containingwool. In an attemptto institutea 26% cut-backin the use of fabrics, the War ProductionBoard drew up regulationsfor the wartimemanufactureof what Esquiremagazinecalled, 'streamlinedsuits by Uncle Sam.'9The regulations effectively forbade the manufactureof zoot-suits and most legitimate tailoring companiesceased to manufactureor advertiseany suits that fell outside the War Production Board's guide lines. However, the demand for zoot-suits did not decline and a network of bootleg tailors based in Los Angeles and New York continuedto manufacturethe garments.Thusthe polarizationbetweenservicemen and pachucos was immediatelyvisible: the chino shirt and battledresswere evidently uniformsof patriotism,whereaswearinga zoot-suit was a deliberateand publicway of floutingthe regulationsof rationing.The zoot-suitwas a moral and social scandalin the eyes of the authorities,not simplybecause it was associated with petty crimeand violence, but becauseit openly snubbedthe laws of rationing. In the fragile harmonyof wartime society, the zoot-suiterswere, accordingto The Zoot-suitand Style Warfare 81 Octavio Paz, 'a symbolof love and joy or of horrorand loathing,an embodiment of liberty, of disorder,of the forbidden."0 The zoot-suit riots, which were initially confined to Los Angeles, began in the first few days of June 1943. During the first weekend of the month, over 60 zoot-suiterswere arrestedand chargedat Los Angeles County jail, after violent and well publicizedfightsbetween servicemenon shore leave and gangs of Mexican-Americanyouths. In orderto preventfurtheroutbreaksof fighting,the police patrolled the eastern sections of the city, as rumoursspread from the military bases that servicemenwere intendingto form vigilantegroups. The Washington Post's reportof the incidents,on the morningof Wednesday9 June 1943, clearly saw the events from the point of view of the servicemen. Disgustedwith being robbedand beatenwith tire irons, weightedropes, belts and fists employedby overwhelmingnumbersof the youthfulhoodlums,the uniformedmen passed the word quietly amongthemselvesand opened their campaignin force on Fridaynight. At centraljail, where spectatorsjammedthe sidewalksand police made no efforts to halt auto loads of servicemenopenly cruisingin searchof zootsuiters, the youths streamedgladly into the sanctityof the cells after being snatchedfrombarrooms, pool hallsand theatersand strippedof theirattire." Duringthe ensuingweeks of rioting,the ritualisticstrippingof zoot-suitersbecame the major means by which the servicementre-establishedtheir status over the pachucos. It became commonplacefor gangs of marinesto ambushzoot-suiters, stripthem down to their underwearand leave them helplessin the streets. In one particularlyviciousincident,a gangof drunkensailorsrampagedthrougha cinema after discoveringtwo zoot-suiters.They draggedthe pachucos on to the stage as the film was being screened, strippedthem in front of the audienceand as a final insult, urinatedon the suits. The press coverageof these incidentsrangedfrom the carefuland cautionary liberalismof The Los Angeles Times to the more hystericalhate-mongeringof WilliamRandolphHearst'swest coast papers. Although the practiceof stripping and publiclyhumiliatingthe zoot-suiterswas not promptedby the press, several reportsdid little to discouragethe attacks: . . .zoot-suits smoulderedin the ashes of street bonfireswherethey had been tossed by grimly methodical tank forces of service men.... The zooters, who earlierin the day had spreadboaststhat they were organizedto 'killeverycop' they could find, showed no inclinationto try to make good their boasts.... Searchingpartiesof soldiers, sailorsand Marineshuntedthem out and drove them out into the open like birddogs flushingquail. Procedurewas standard: grab a zooter. Take off his pants and frock coat and tear them up or burn them. Trim the 'Argentine Ducktail' haircut that goes with the screwy costume.12 The second week of June witnessed the worst incidents of rioting and public disorder.A sailorwas slashedand disfiguredby a pachucogang;a policemanwas run down when he tried to question a car load of zoot-suiters;a young Mexican was stabbedat a partyby drunkenMarines;a trainloadof sailorswere stoned by A young zoot-suiteris protectedfrom a racistmob duringan outbreakof street violence in Detroit. Two pachuco zoot-suiters,one strippedto his underwear,hiebeaten and humiliatedmna Los Angeles street. The Zoot-suitand Style Warfare 83 pachucos as their train approachedLong Beach; streetfightsbroke out daily in San Bernardino;over 400 vigilantestoured the streets of San Diego looking for zoot-suiters,and manyindividualsfrom both factionswere arrested.13On 9 June, The Los Angeles Times publishedthe first in a series of editorialsdesigned to reduce the level of violence, but which also tried to allay the growingconcern about the racialcharacterof the riots. To preservethe peace and good name of the Los Angeles area, the strongest measuresmust be taken jointly by the police, the Sheriff'soffice and Army and Navy authorities,to preventany furtheroutbreaksof 'zoot suit' rioting. While membersof the armedforces receivedconsiderableprovocationat the hands of the unidentifiedmiscreants,such a situation cannot be cured by indiscriminateassaulton every youth wearinga particulartype of costume. It would not do, for a large numberof reasons, to let the impression circulatein South America that persons of Spanish-Americanancestrywere being singledout for mistreatmentin SouthernCalifornia.And the incidents here were capableof being exaggeratedto give that impression.14 THE CHIEF, THE BLACK WIDOWSAND THE TOMAHAWKKID The pleas for tolerance from civic authoritiesand representativesof the church and state had no immediateeffect, and the riots becamemore frequentand more violent. A zoot-suitedyouth was shot by a specialpolice officerin Azusa, a gang of pachucoswere arrestedfor riotingand carryingweaponsin the LincolnHeights area; 25 black zoot-suiterswere arrestedfor wreckingan electricrailwaytrainin Watts, and 1000 additionalpolice were draftedinto East Los Angeles. The press coverage increasinglyfocused on the most 'spectacular'incidents and began to identifyleadersof zoot-suitstyle. On the morningof Thursday10 June 1943,most newspaperscarriedphotographsand reportson three 'notorious'zoot-suit gang leaders. Of the thousandsof pachucosthat allegedlybelongedto the hundredsof zoot-suit gangs in Los Angeles, the press singled out the arrests of Lewis D English, a 23-year-old-black,chargedwith felony and carryinga '16-inchrazor sharp butcher knife;' Frank H Tellez, a 22-year-oldMexican held on vagrancy charges, and another Mexican, Luis 'The Chief Verdusco (27 years of age), allegedlythe leader of the Los Angeles pachucos.15 The arrests of English, Tellez and Verdusco seemed to confirm popular perceptions of the zoot-suiters widely expressed for weeks prior to the riots. Firstly,thatthe zoot-suitgangswere predominantly,but not exclusively,comprised of black and Mexicanyouths. Secondly, that many of the zoot-suiterswere old enough to be in the armed forces but were either avoidingconscriptionor had been exemptedon medicalgrounds.Finally,in the case of FrankTellez, who was photographedwearinga pancakehat with a rear feather, that zoot-suit style was an expensive fashion often funded by theft and petty extortion. Tellez allegedly wore a colourfullong drapecoat that was 'partof a $75 suit' and a pair of pegged trousers'very full at the knees and narrowat the cuffs' whichwere allegedlypart of anothersuit. The captionof the AssociatedPressphotographindignantlyadded that 'Tellez holds a medicaldischargefrom the Army'.16Whatnewspaperreports tended to suppresswas informationon the Marineswho were arrestedfor inciting 84 History WorkshopJournal riots, the existence of gangs of white Americanzoot-suiters,and the opinionsof Mexican-Americanservicemenstationedin California,who were part of the wareffort but who refusedto take part in vigilanteraidson pachuco hangouts. As the zoot-suit riots spread throughoutCalifornia,to cities in Texas and Arizona, a new dimensionbegan to influencepress coverage of the riots in Los Angeles. On a day when 125 zoot-suitedyouths clashed with Marinesin Watts and armed police had to quell riots in Boyle Heights, the Los Angeles press concentratedon a razorattackon a local mother, Betty Morgan.What distinguished this incident from hundredsof comparableattacks was that the assailants were girls. The press related the incident to the arrest of Amelia Venegas, a womanzoot-suiterwho was chargedwith carrying,and threateningto use, a brass knuckleduster.The revelationthat girlswere activewithinpachucosubcultureled to consistentpresscoverageof the activitiesof two female gangs:the Slick Chicks and the Black Widows.17The lattergangtook its name fromthe members'distinctive dress, black zoot-suit jackets, short black skirtsand black fish-netstockings. In retrospectthe Black Widows, and their active part in the subculturalviolence of the zoot-suit riots, disturb conventional understandingsof the concept of pachuquismo. As Joan W Moore impliesin Homeboys,her definitivestudy of Los Angeles youth gangs, the concept of pachuquismois too readily and unproblematically equated with the better known concept of machismo.18Undoubtedly,they share certain ideologicaltraits, not least a swaggeringand at times aggressivesense of power and bravado, but the two concepts derive from different sets of social definitions.Whereasmachismocan be definedin terms of male power and sexuality, pachuquismopredominantlyderives from ethnic, generationaland classbased aspirations,and is less evidentlya question of gender. What the zoot-suit riots brought to the surface was the complexity of pachuco style. The Black Widowsand their aggressiveimageconfoundedthe pachucostereotypeof the lazy male delinquentwho avoidedconscriptionfor a life of dandyismand petty crime, and reinforcedradicalreadingsof pachucosubculture.The Black Widowswere a reminderthat ethnic and generationalalienationwas a pressingsocial problem and an indicationof the tensionsthatexistedin minority,low-incomecommunities. Althoughdetailedinformationon the role of girlswithinzoot-suitsub-culture is limitedto very briefpressreports,the appearanceof femalepachucoscoincided with a dramaticrise in the delinquencyrates amongstgirls aged between 12 and 20 years old. The disintegrationof traditionalfamily relationshipsand the entry of young women into the labour force undoubtedlyhad an effect on the social roles and responsibilitiesof female adolescents, but it is difficultto be precise about the relationshipsbetween changedpatternsof social experienceand the rise in delinquency.However, war-timesociety broughtabout an increasein unprepared and irregularsexual intercourse,which in turn led to significantincreases in the rates of abortion,illegitimatebirthsand venerealdiseases. Althoughstatistics are difficultto trace, there are many indicationsthat the war years saw a remarkableincreasein the numbersof young women who were taken into social care or referredto penal institutions,as a result of the specific social problems they had to encounter. Later studiesprovideevidence that young women and girlswere also heavily involved in the traffic and transactionof soft drugs. The pachuco sub-culture withinthe Los Angeles metropolitanareawas directlyassociatedwitha widespread The Zoot-suitand Style Warfare 85 growth in the use of marijuana.It has been suggested that female zoot-suiters concealed quantitiesof drugs on their bodies, since they were less likely to be closelysearchedby male membersof the law enforcementagencies.Unfortunately, the absence of consistent or reliable informationon the female gangs makes it particularlydifficultto be certainabout their statuswithinthe riots, or their place withintraditionsof feminineresistance.The Black Widowsand Slick Chickswere spectacularin a sub-culturalsense, but their black drapejackets, tight skirts,fish net stockingsand heavily emphasisedmake-up, were ridiculedin the press. The Black Widowsclearlyexisted outsidethe orthodoxiesof war-timesociety:playing no part in the industrialwar effort, and openly challengingconventionalnotions of femininebeauty and sexuality. Towardsthe end of the second week of June, the riots in Los Angeles were dying out. Sporadicincidentsbroke out in other cities, particularlyDetroit, New York and Philadelphia,where two membersof Gene Krupa'sdance band were beaten up in a station for wearingthe band'szoot-suit costumes;but these, like the residual events in Los Angeles, were not taken seriously. The authorities failed to read the inarticulatewarningsigns profferedin two separateincidentsin California:in one a zoot-suiter was arrested for throwing gasoline flares at a theatre; and in the second anotherwas arrestedfor carryinga silver tomahawk. The zoot-suit riots had become a public and spectacularenactment of social disaffection.The authoritiesin Detroit chose to dismissa zoot-suitriot at the city's Cooley High School as an adolescentimitationof the Los Angeles disturbances.19 Withinthree weeks Detroit was in the midstof the worst race riot in its history.20 The United Stateswas still involvedin the war abroadwhen violent events on the home front signalledthe beginningsof a new era in racialpolitics. OFFICIALFEARS OF FIFTH COLUMNFASHION Official reactions to the zoot-suit riots varied enormously. The most urgent problemthat concernedCalifornia'sState Senatorswas the adverseeffect that the events mighthave on the relationshipbetweenthe United Statesand Mexico.This concern stemmed partly from the wish to preservegood internationalrelations, but rathermore from the significanceof relationswith Mexico for the economy of SouthernCalifornia,as an item in the Los Angeles Timesmade clear. 'In San Francisco Senator Downey declared that the riots may have 'extremely grave consequences'in impairingrelationsbetween the United States and Mexico, and may endangerthe programof importingMexicanlabor to aid in harvestingCaliforniacrops.'21These fearswere compoundedwhenthe MexicanEmbassyformally drew the zoot-suit riots to the attentionof the State Department.It was the fear of an 'internationalincident'22 that couldonly have an adverseeffect on California's economy, ratherthan any real concernfor the social conditionsof the MexicanAmericancommunity,that motivatedGovernorWarrenof Californiato order a publicinvestigationinto the causes of the riots. In an ambiguouspress statement, the Governorhinted that the riots may have been instigatedby outside or even foreign agitators: As we love our countryand the boys we are sending overseas to defend it, we are all duty bound to suppressevery discordantactivitywhich is designed The zoot-suitstyle reachesLondon. A young couple dance on the floor of a ballroomin Hammersmithcirca 1944 A gang of Detroit zoot-suitersline up againstthe wall of a hotel. As the youthswait to be searchedby the police their girlfriendsstand in single file along the edge of the sidewalk. The Zoot-suitand Style Warfare 87 to stir up internationalstrife or adverselyaffect our relationshipswith our allies in the United Nations.23 The zoot-suitriots provokedtwo relatedinvestigations;a fact findinginvestigative committeeheadedby AttorneyGeneralRobertKennyand an un-Americanactivities investigationpresidedover by State SenatorJackB Tenney. The un-American activitiesinvestigationwas ordered 'to determinewhether the present zoot-suit riots were sponsoredby Nazi agenciesattemptingto spreaddisunitybetween the United States and Latin-Americancountries'.24SenatorTenney, a memberof the un-American Activities committee for Los Angeles County, claimed he had evidence that the zoot-suitriots were 'axis-sponsored'but the evidencewas never presented.25However, the notion that the riots might have been initiated by outside agitators persisted throughoutthe month of June, and was fuelled by Japanese propagandabroadcastsaccusing the North American governmentof ignoringthe brutalityof US marines.The argumentsof the un-Americanactivities investigationwere given a certainamountof credibilityby a Mexicanpastorbased in Watts, who accordingto the press had been 'a pretty rough customerhimself, servingas a captainin PanchoVilla's revolutionaryarmy.'26ReverendFrancisco Quintanilla,the pastorof the MexicanMethodistchurch,was convincedthe riots were the resultof fifthcolumnists.'Whenboys startattackingservicemenit means the enemy is right at home. It means they are being fed vicious propagandaby enemy agentswho wish to stir up all the racialand class hatredsthey can put their evil fingerson.'27 The attentiongiven to the dubiousclaimsof nazi-instigationtended to obfuscate other more credible opinions. Examination of the social conditions of pachuco youths tended to be marginalizedin favour of other more 'newsworthy' angles. At no stage in the presscoveragewere the opinionsof communityworkers or youth leaderssought, and so, ironically,the most progressiveopinionto appear in the major newspaperswas offered by the Deputy Chief of Police, EW Lester. In press releases and on radio he provideda short historyof gang subculturesin the Los Angeles area and then tried, albeit briefly,to place the riots in a social context. The Deputy Chief said most of the youths came from overcrowdedcolorless homes that offered no opportunitiesfor leisure-timeactivities. He said it is wrong to blame law enforcementagenciesfor the presentsituation,but that society as a whole must be chargedwith mishandlingthe problems.28 On the morningof Friday, 11 June 1943, The Los Angeles Timesbroke with its regularpracticesand printed an editorial appeal, 'Time For Sanity'on its front page. The main purpose of the editorialwas to dispel suggestionsthat the riots were racially motivated, and to challenge the growing opinion that white servicemenfrom the SouthernStateshad activelycolludedwith the police in their vigilantecampaignagainstthe zoot-suiters. There seems to be no simple or complete explanationfor the growthof the grotesque gangs. Many reasons have been offered, some apparentlyvalid, some farfetched. But it does appear to be definitely established that any attemptsat curbingthe movementhave had nothingwhateverto do with race 88 History WorkshopJournal persecution,althoughsome elements have loudly raised the cry of this very thing.29 A month later, the editorial of July's issue of Crisis presented a diametrically opposed point of view: These riots would not occur - no matter what the instant provocation- if the vast majorityof the population,includingmore often than not the law enforcementofficers and machinery,did not share in varying degrees the belief that Negroes are and must be kept second-classcitizens.30 But this view got short shrift, particularlyfrom the authorities, whose initial response to the riots was largelyretributive.Emphasiswas placed on arrestand punishment.The Los Angeles City Councilconsidereda proposalfrom Councillor Norris Nelson, that 'it be made a jail offense to wear zoot-suitswith reat pleats withinthe city limits of LA'31,and a discussionensued for over an hour before it was resolved that the laws pertainingto rioting and disorderlyconduct were sufficientto containthe zoot-suitthreat. However, the councildid encouragethe War ProductionBoard (WPB) to reiterateits regulationson the manufactureof suits. The regionaloffice of the WPB based in San Franciscoinvestigatedtailors manufacturingin the area of men's fashionand took steps 'to curbillegal production of men's clothing in violation of WPB limitation orders.'32Only when GovernorWarren'sfact-findingcommissionmade its publicrecommendationsdid the politicalanalysisof the riots go beyond the firstprinciplesof punishmentand proscription.The recommendationscalled for a more responsibleco-operation from the press; a programmeof special trainingfor police officers working in multi-racialcommunities;additionaldetention centres; a juvenile forestrycamp for youth underthe age of 16; an increasein militaryand shore police; an increase in the youth facilities provided by the church; an increase in neighbourhood recreationfacilitiesand an end to discriminationin the use of publicfacilities. In addition to these measures, the commissionurged that arrestsshould be made withoutundue emphasison membersof minoritygroupsand encouragedlawyers to protect the rights of youths arrestedfor participationin gang activity. The findingswere a delicatebalanceof punishmentandpalliative;it madeno significant mention of the social conditionsof Mexicanlabourersand no recommendations about the kind of publicspendingthat would be needed to alter the social experiences of pachuco youth. The outcome of the zoot-suit riots was an inadequate, highly localized and relativelyineffectivebody of short term public policies that providedno guidelinesfor the more serious riots in Detroit and Harlem later in the same summer. THE MYSTERYOF THE SIGNIFYINGMONKEY The pachucois the prey of society, but instead of hiding he adorns himself to attract the hunter's attention. Persecutionredeems him and breaks his solitude: his salvationdepends on him becomingpart of the very society he appearsto deny.33 The Zoot-suit and Style Warfare 89 The zoot-suitwas associatedwith a multiplicityof differenttraitsand conditions. It was simultaneouslythe garb of the victim and the attacker,the persecutorand the persecuted, the 'sinister clown' and the grotesque dandy. But the central oppositionwas between the style of the delinquentand that of the disinherited. To wear a zoot-suitwas to risk the repressiveintoleranceof wartimesociety and to invite the attention of the police, the parent generation and the uniformed membersof the armedforces. For manypachucosthe zoot-suitriots were simply hightimesin Los Angeles when momentarilythey had control of the streets; for othersit was a realizationthat they were outcastsin a society that was not of their making.For the blackradicalwriter,ChesterHimes, the riotsin his neighbourhood were unambiguous:'Zoot Riots are Race Riots.'34For other contemporary commentatorsthe wearing of the zoot-suit could be anythingfrom unconscious dandyism to a conscious 'political' engagement. The zoot-suit riots were not 'political'riots in the strictestsense, but for manyparticipantsthey were an entry into the languageof politics, an inarticulaterejection of the 'straightworld' and its organization. It is remarkablehow many post-waractivistswere inspiredby the zoot-suit disturbances.Luis Valdez of the radicaltheatrecompany,El Teatro Campesino, allegedly learned the 'chicano'from his cousin the zoot-suiterBilly Miranda.35 The novelists Ralph Ellison and RichardWright both conveyed a literary and politicalfascinationwith the powerand potentialof the zoot-suit.One of Ellison's editorialsfor the journalNegro Quarterlyexpressedhis own sense of frustration at the enigmaticattractionof zoot-suitstyle. A third major problem, and one that is indispensableto the centralization and directionof power is that of learningthe meaningof myths and symbols which aboundamongthe Negro masses. For withoutthis knowledge,leadership, no matterhow correctits program,will fail. Muchin Negro life remains a mystery;perhapsthe zoot-suitconcealsprofoundpoliticalmeaning;perhaps the symmetricalfrenzy of the Lindy-hopconceals clues to great potential powers, if only leaders could solve this riddle.36 AlthoughEllison'sremarksare undoubtedlycompromisedby theirown mysterious idealism, he touches on the zoot-suit'smajor source of interest. It is in everyday ritualsthat resistancecan find naturaland unconsciousexpression.In retrospect, the zoot-suit'shistorycan be seen as a point of intersection,between the related potential of ethnicityand politics on the one hand, and the pleasuresof identity and differenceon the other. It is the zoot-suit'spolitical and ethnic associations that have made it such a rich referencepoint for subsequentgenerations.From the music of TheloniousMonk and Kid Creole to the jazz-poetryof LarryNeal, the zoot-suithas inheritednew meaningsand new mysteries.In his book Hoodoo Hollerin' Bebop Ghosts, Neal uses the image of the zoot-suit as the symbol of BlackAmerica'sculturalresistance.For Neal, the zoot-suitceasedto be a costume and became a tapestryof meaning,wheremusic,politicsand social actionmerged. The zoot-suit became a symbolfor the enigmasof Black cultureand the mystery of the signifyingmonkey: But there is rhythm here Its own special substance. 90 History WorkshopJournal I hear Billie sing, no Good Man, and dig Prez, wearingthe Zoot suit of life, the Porkpiehat tiltedat the correctangle; throughthe Harlemsmoke of beer and whisky,I understandthe mysteryof the SignifyingMonkey.37 The authorwishes to acknowledgethe supportof the BritishAcademyfor the researchfor this article. 1 Ralph Ellison InvisibleMan New York 1947p 380 2 InvisibleMan p 381 3 'Zoot Suit Originatedin Georgia'New York Times11 June 1943p 21 4 For the most extensivesociologicalstudyof the zoot-suitriots of 1943see RalphH Turnerand Samuel J Surace 'Zoot Suiters and Mexicans:Symbolsin Crowd Behaviour' AmericanJournalof Sociology62 1956pp 14-20 5 OctavioPaz The Labyrinthof SolitudeLondon 1967pp 5-6 6 Labyrinthof Solitudep 8 7 As note 6 8 See KL Nelson (ed) TheImpactof Waron AmericanLife New York 1971 9 OE Schoefflerand W Gale Esquire'sEncyclopaediaof Twentieth-Century Men's FashionNew York 1973p 24 10 As note 6 11 'Zoot-SuitersAgain on the Prowl as Navy Holds Back Sailors'WashingtonPost 9 June 1943p 1 12 Quoted in S MenefeeAssignmentUSA New York 1943p 189 13 Details of the riots are taken from newspaperreportsand press releases for the weeks in question, particularlyfrom the Los Angeles Times,New York Times,Washington Post, WashingtonStarand TimeMagazine 14 'StrongMeasuresMust be Taken AgainstRioting'Los Angeles Times9 June 1943 p4 15 'Zoot-SuitFightingSpreadsOn the Coast'New York Times10 June 1943p 23 16 As note 15 17 'Zoot-GirlsUse Knife in Attack' Los Angeles Times11 June 1943p 1 18 Joan W Moore Homeboys:Gangs,Drugsand Prisonin the Barriosof Los Angeles Philadelphia1978 19 'Zoot Suit WarfareSpreadsto Pupils of Detroit Area' WashingtonStar 11 June 1943 p 1 20 Although the Detroit Race Riots of 1943 were not zoot-suit riots, nor evidently about 'youth' or 'delinquency',the social context in which they took place was obviously comparable.For a lengthystudyof the Detroit riots see R Shogunand T CraigTheDetroit Race Riot: a studyin violencePhiladelphiaand New York 1964 21 'Zoot Suit WarInquiryOrderedby Governor'Los Angeles Times9 June 1943p A 22 'WarrenOrdersZoot Suit Quiz; Quiet Reigns After Rioting' Los Angeles Times 10 June 1943p 1 23 As note 22 24 'TenneyFeels Riots Causedby Nazi Move for Disunity'Los Angeles Times9 June 1943 p A 25 As note 24 26 'WattsPastorBlamesRiots on FifthColumn'Los AngelesTimes11 June 1943p A 27 As note 26 28 'CaliforniaGovernorAppeals for Quellingof Zoot Suit Riots' WashingtonStar 10 June 1943pA3 29 'Time for Sanity'Los Angeles Times11 June 1943p 1 30 'The Riots' The CrisisJuly 1943p 199 31 'Ban on FreakSuits Studiedby Councilmen'Los Angeles Times9 June 1943p A3 33 Labyrinthof Solitudep 9 34 ChesterHimes 'Zoot Riots are Race Riots' TheCrisisJuly1943;reprintedin Himes Black on Black: Baby Sisterand SelectedWritingsLondon 1975 35 El Teatro Campesinopresentedthe first Chicanoplay to achieve full commercial Broadwayproduction.The play, writtenby LuisValdezandentitled'Zoot Suit'was a drama 91 The Zoot-suit and Style Warfare documentaryon the Sleepy Lagoonmurderand the events leadingto the Los Angeles riots. (The Sleepy Lagoon murderof August 1942 resulted in 24 pachucos being indicted for conspiracyto murder.) 36 Quoted in Larry Neal 'Ellison's Zoot Suit' in J Hersey (ed) Ralph Ellison: A Collectionof CriticalEssays New Jersey 1974p 67 37 From Larry Neal's poem 'Malcolm X: an Autobiography'in L Neal Hoodoo Hollerin'Bebop GhostsWashingtonDC 1974p 9 ..... ....... Ca 4S AM.. 0......