The Revolutionary Alliance between John Muir and Theodore

advertisement

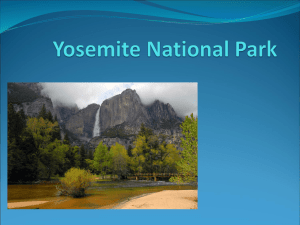

Wentz 1 LEAVINGBEHINDMORETHANFOOTPRINTS : The Revolutionary Alliance between John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt and the Lasting Reform on the United States Conservation Movement Sierra Wentz Senior Division Word Count: 2,497 Wentz 2 Though the men involved have long since packed up their campsite and headed home, there is still one curious bit of history memorializing John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt‟s time together – a simple, wooden, umber-colored plaque which reads; “On this site President Theodore Roosevelt sat beside a campfire with John Muir on May 17, 1903 and talked forest good. Muir urged the president to work for preservation of priceless remnants of America’s wildlife. At this spot one of our country’s foremost conservationists received great inspiration” (Yosemite Online Library). This plaque does much more than encapsulate one camping trip between outdoor enthusiasts – it represents an alliance, revolutionary in its time, its nature, and its accomplishments, as well as mighty reactions and far-reaching reforms. When Muir recognized California‟s inability to properly care for and protect Yosemite Valley (Appendix II) and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove (Appendix III), lands which had been granted to California in 1864, he convinced Roosevelt to pull the lands into federal control. The revolutionary alliance between Muir and Roosevelt led to the subsequent passing of legislation which reformed not only the care for Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove but twentieth century United States environmentalism and conservation as well; therefore, the alliance and the legislation passed is a superb example of revolution, reaction, and reform in history. Nineteenth Century Conservation Efforts in the United States In the late nineteenth century United States, environmentalism was gaining support due to authors such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, a transcendentalist thinker, and Henry David Thoreau, who wrote on environmental history (National Park Service Website). The upper class ventured Wentz 3 into nature during their vacations with the help of trail guides. Society was beginning to realize the importance of conserving land for recreational use and enjoyment. In 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed an act¹ which protected Yosemite Valley for the purpose of conservation and recreation (Egan 33). Early in the conservation movement, land was seen solely as the state‟s responsibility. Naturally, this act authorized state – not federal – control of the land.Sheep grazing and herding along with commercial use, such as logging, continued due to the lack of strong leadership – California had become a state only fourteen years prior. Insufficient funds to care for the land and private companies‟ strong influence in state affairs greatly contributed to the degradation of the land. Environmentalist groups, such as the Sierra Club, became suspicious of misuse when native grasses and plants became scarce due to grazing (Greene 365). In 1890 Yosemite National Park, under federal jurisdiction, was created surrounding Yosemite Valley; however, Yosemite Valley was not included and remained in state control, leading to an imperium in imperio – that is, a ruling within a ruling (H. R. Rep. No. 2339). This dual ownership caused great friction and unnecessary harm to the valley, such as when a fire ignited near the border of state and federal control and the state and military superintendents argued for days over who held responsibility until the fire overtook and destroyed a large part of the forest (Cong. Rec. Vol. 40, Part 9). Early trailblazers of the conservation movement, such as Muir, saw that reform was necessary if the United States‟ land was to be preserved. The Camping Trip of the Century The two key players of the alliance – Muir and Roosevelt – were of very different backgrounds, but each had qualities which contributed to revolutionary protection for Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove. Muir, born in Scotland in 1838, was an avid botanist, Wentz 4 outdoorsman, and is known posthumously as the United States‟ first environmentalist. His fight to save our country‟s wildlife began in 1876, five years after spending his first summer in Yosemite when he began to lobby for forest protection and conservation. Theodore Roosevelt, born in 1858 in New York, was a politician, president, and environmentalist; he served in the New York State Assembly, several military-type positions, and as the twenty-sixth president of the United States (Theodore Roosevelt Association Website). He enjoyed being in the wilderness, much the same as Muir; unlike Muir, however, he was an enthusiastic game hunter. Naturally, Roosevelt admired Muir‟s zeal for conservation, which matched Roosevelt‟s own feistiness (Egan 43). At the time of the famed camping trip, Muir was preparing to embark on a worldwide campaign for conservation. Upon learning this, Roosevelt sent him a letter, successfully coaxing him on the camping trip, saying, “I do not want anyone with me but you . . . and I want to drop politics absolutely for four days and just be out in the open with you” (Brinkley 543). Thus, in May of 1903, Roosevelt met up with Muir in Yosemite Valley and the revolutionary duo spent four days together, trekking through the valley and unknowingly participating in the most influential camping trip in the United States‟ history (Appendix I). Roosevelt chose to camp without his Secret Service guards and dismissed the press in an effort to fully experience nature with Muir. They hiked through Mariposa Grove, Sentinel Dome, Glacier Point, and Yosemite Valley; Muir spoke of the degradation of our geography and urged Roosevelt to protect the land. Roosevelt needed little convincing of the commercial misuse of forests, however – in 1900, the cut of Redwoods was about 520,000,000 board feet in California alone (Roa 124). This alliance was revolutionary because two very unlikely men – one an outdoors-loving hunter, the other a complete preservationist – were able to merge together and set aside their differences. Like the Wentz 5 very campfire they sat next to under the stars, they would spark a bright, robust flame in the fight to conserve the United States‟ natural land. Through this revolutionary alliance, the land would not only receive greater protection – Muir and Roosevelt would reform the conservation movement and construct a model for federally protected parks. Opposition: Local Developers Against Conservationists As with any revolution, there was a reaction from both parties – and an opposition to reform. Not everyone welcomed the power shift from partial state control to complete federal control. The transfer from state to federal control was an embarrassment to California, because it showed California‟s inability to provide proper protection. Larger companies and corporations had advocated for federal control, along with conservationists and environmentalists. Some, such as the Sierra Cluband Southern Pacific Railroad, believed the park would benefit from unified control. For example, the Sierra Club‟s definition of the highest and best use of the landwas tourism and public education on environmentalism and conservation; under federal control, the park would receive funds for construction of bridges, roads, and trails, as well as hotels and a telephone system in the event of forest fires. However, local developers and concessionaires reacted against the power shift. They believed the state was more capable of commercial enterprise and development (Runte 84-85). The Sierra Club made a strong argument for federal control when they contrasted the care of Yellowstone National Park, under the jurisdiction of the United States, with the misuse of Yosemite Valley in a Congressional publication from 1906. They illustrated the inadequate care California was providing for the land, pointing out the dilapidated state of the entrance roads as well as tourist accommodations. They then contrasted Yosemite‟s care with that of the Yellowstone National Park, with its large budget, usable roads and trails, and the high-quality Wentz 6 hotels² (Annual Reports from the Department of the Interior). The indisputable care the federal government could provide for this land was indeed revolutionary. The budget for the care of Yellowstone was considerably larger than the funds appropriated for Yosemite. The park rangers and the security they could provide would far surpass the present policing. Lastly, the accommodations for tourism, recreation, and conservation – the very core of the land‟s legislative protection – would be stronger, larger, and safer than the state could provide at that time. For example, a Senate Report dated 17 May 1906 stated that the numbers for tourism to the valley were rising yearly – in 1864 there were 147 visitors to the valley, but in 1903, 8,376 tourists visited the land (S. Rep. No. 3623). This growing tourism rate also represented a maturing conservation movement. The transfer to federal control would become integral to the land‟s preservation and the conservation revolution in the twentieth century. The Passing of the Joint Resolution On 11 June 1906, after almost a full year of drafts and changes, the Joint Resolution3 was passed with two-thirds in favor of federal control (Cong. Rec. Vol. 40, Part 7). This act pulled Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove into one combined tract of land, creating a single national park. For nearly thirty years the two lands had been owned separately; however, their size and location made it logical to govern the lands as one. This revolutionary resolution was one of the first instances of the United States protecting land for the purpose of conservation (National Park Service Website). The first draft of the resolution, passed 3 March 1905, begins by acknowledging California‟s surrender of the land once granted to them under the Yosemite Grant of 1864 and assumes the United States will undertake the responsibilities California once had for public use, resort, and recreation4 (H.R. Rep. No. 2339). The final resolution in 1906 explicitly protects the land from development, gives the Secretary of the Interior the power to Wentz 7 request funding for the valley, stipulates no timber or other development will occur in the land without the consent of the Secretary, and requires all revenues from the land will be paid into the Treasury to be expended under the Secretary5 (Joint Resolution No. 27). However, this reform to the preservation of the land did not come without a price: the size of the park was significantly reduced – from 1,512 square miles in 1890 to 1,124.41 square miles – a loss of about 400 square miles (See Appendix IV). In a House of Representatives Report, Secretary of the Interior Hitchcock documents how the elimination of land would permit the construction of roads to allow southern Californians access to the valley; he also states the line of proposed road would not damage the natural land and the timber groves would be preserved as well. This compromiseillustrates the reform on the conservation movement because more people would be able to use the land for enjoyment and recreation than before (H.R. Rep. No. 2339). This legislation, as a result of Muir and Roosevelt‟s alliance, revolutionized the conservation movement in the United States not only because of federal oversight but also because the park was made accessible to so many citizens outside of the immediate area; through these accomplishments the United States was able to achieve a strong foundation for future national parks. After the Joint Resolution – Are More Revolutions Necessary? Certainly, Yosemite National Park has flourished under federal control. The park contains 747,956 acres, 214 miles of paved roads, twenty miles of bicycle paths, 800 miles of trails, lodging throughout the park, 1,504 campground sites, and 131 bridges (See Appendix V). In 2010, there were 4,047,880 tourists to the park (National Park Service Website). Had the park been kept in state hands, it may not be as successful – or as pristine – as it is today. However, there are current debates over possible reforms to the way our country‟s natural land is managed. Wentz 8 The idea of “park privatization” – that is, private enterprises paying the expenses associated with operating and maintaining the park – mostly state parks – and keeping the customer-paid fees at the gate as revenue – is beginning to take hold, drawing an intense reaction and compelling arguments from both parties. Robert Righter, a historian, university professor, and author, has been a member of the Sierra Club for over thirty-five years; he is against park privatization. In an interview on 30 January 2012, he stated, “National parks are the [remaining pieces] of America . . . for the American people.” Among the list of activities he believed would occur under privatization, he listed “hunting, off-roading vehicles, and profit-making” – in other words, destruction of nature. Righter believes profit is a strong – and harmful – motivator for supporters of park privatization; he argues privatization companies would be more interested in making a profit than protecting the park. He supports the National Park Service because their protection keeps parks in their natural state. He cited the Yosemite Firefall attraction6, along with the music concerts in the park in the mid-1900‟s, as an example of what might resume under park privatization. He explained that when the Firefall was operating, Yosemite “became an attraction park, not a nature park.” Under park privatization, he believes the focus of our parks would shift from preservation to profit. Warren Meyer represents the other side of this debate. The founder of Recreation Resource Management, one of the nation‟s leading private permit operators, Meyer seeks to keep the United States‟ parks open and accessible. On his website, Park Privatization, Meyer explains how the efficiency of this practice can keep parks open even in a government shutdown, arguing, “These companies have focused their whole business model on park operations, so they have developed proven processes for park management.” He also states, “Privatizing parks takes Wentz 9 them off the government budget,” which can lead to increased funding for the park from the private companies. In response to the belief that the park will become commercialized, he explains, “It simply is not possible . . . A concessionaire cannot . . . even cut down a tree without written approval from the parks organization . . . It is generally not in the company‟s best interest” (Park Privatization Website). These reactions to possible land conservation reforms are quite similar to those of the early twentieth century when federal control for Yosemite and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove was being debated. Through this contemporary twist on possible reforms to the conservation movement, one can clearly see the reactions – from both private companies and national organizations – are nearly identical to those in 1906. The tangible desire from both parties to revolutionize care for our country‟s land is still as evident today as in 1906. Conclusion to a Conservation Revolution Today, more than a hundred years after Muir and Roosevelt‟s famed camping trip, Yosemite National Park is still teeming with swallows, grasses, sparkling streams, and cool granite mountain ranges – it is literally buzzing with wildlife. This alliance, a superb example of revolution, reaction, and reform in history, achieved not only complete federal protection for one valley, but for hundreds of millions of acres of future wildlife as well. Following the transfer to federal jurisdiction, the United States became aware that the federal government was better equipped to provide strong protection for our country‟s land; currently, there are 397 national parks within the National Park System (National Park Service Website). The transfer of Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove to federal jurisdiction was a gigantic step in ensuring so-called “preserved land” in the United States would be given full protection – as well as supporting resources. The reforms resulting from their alliancecame at a time when the conservation movement was still young and somewhat unstable but fiercely determined to Wentz 10 protect the United States‟ natural land. Muir and Roosevelt left behind far more than just their footprints in Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove – their alliance gave the conservation movement vital momentum to accomplish further revolutions in conservation. This momentum, like the very swallows, grasses, and insects in the valley, is vibrant, lively, and undoubtedly evident today. Wentz 11 Notes 1. This act, signed 30 June 1864, is informally known as the Yosemite Grant; its formal name is “An Act Authorizing a Grant to the State of California of the Yosemite Valley and of the Land Embracing the Mariposa Big Tree Grove.” 2. “The State is unable to properly care for the Yosemite Valley . . . the main stage roads on the floor of the valley leading to the village area are in a deplorable condition. The accommodations provided for visitors have been inadequate for years . . . In marked contrast . . . is the management of the Yellowstone National Park by the Federal Government . . . During the three years 1901-3 Congress appropriated nearly $70,000 for the care and maintenance of the Yellowstone. The best of the skilled engineers are employed in the construction of the roads and trails . . . the roads are broad highways with steel and concrete bridges. The hotels are . . . first class in every respect.” 3. The full name of this legislation is the “Joint Resolution Accepting the Recession by the State of California of the Yosemite Valley Grant and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove.” 4. “The State of California does hereby recede and regrant unto the United States of America . . . the [land] . . . in trust for public use, resort, and recreation by the act of Congress entitled „An act authorizing a grant to the State of California of the Yosemite Valley and . . . the Mariposa Big Tree Grove‟ . . . and the State of California does hereby relinquish unto the United States of America and resign the trusts created and granted by the said act of Congress.” 5. “Yosemite National Park . . . reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale. . . The Secretary of the Interior may require the payment of such price as he may deem proper . . . It shall be stipulated that no logs or timber shall be hauled over . . . without consent of the Secretary of the Interior . . . That all revenues derived . . . shall be paid into the Treasury of the Wentz 12 United States, to be expended under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior in the management, protection, and improvement of the Yosemite National Park.” 6. The Yosemite Firefall was an attraction in the park from 1872 to 1968 in which burning embers were dropped from Glacier Point to the valley below – a distance of about 3,000 feet. This practice was stopped in 1968 by the National Park Service because of the large number of visitors it brought, as well as the fact that it was not a natural event. \ Wentz 13 Appendix I Theodore Roosevelt (left) and John Muir (right) on Glacier Point in Yosemite Valley, 1903 Wentz 14 Appendix II Yosemite Valley, circa 1906 Wentz 15 Appendix III Mariposa Big Tree Grove, circa 1906 Wentz 16 Appendix IV Boundary Changes in Yosemite National Park from 1864 to 1906 Wentz 17 Appendix V Yosemite Valley in the Twenty-First Century Wentz 18 Annotated Bibliography Personal Communications Burton, Dudley J.Telephone interview. 2 January 2012. This interview with Mr. Burton, head of the Environmental Studies Department at CSU – Sacramento, was helpful because he gave me an overview on the Joint Resolution – both the legislation and its implications – and led me to expand my paper into the present. Righter, Robert. Telephone interview. 30 January 2012. This interview was helpful because Righter is an environmentalist, so he is against park privatization. His viewpoints were used in the section of my paper detailing the modern reaches of the Joint Resolution and the possible future reforms on our country‟s land management. Primary Sources California, Yosemite Valley, Bridal Veil Falls, Wawona Trail.circa 1906. Photograph. District of Columbia. Library of Congress.Web. 28 Dec. 2011. This photograph, taken circa 1906, shows Yosemite Valley in its natural state. This can be seen in Appendix II and was used to illustrate Yosemite Valley‟s true, virginal beauty – beauty which has been protected due to the revolutionary alliance. Cong. Rec. House.59th Cong., 1st sess. Vol. 40, Part 7. 1906: 6,487. Print. This congressional record held the boundary changes of the final Yosemite National Park, as well as the final vote, which was two-thirds in favor thereof. This document – and the others obtained from the National Archives – gave my paper support, strength, and made research very interesting. Cong. Rec. Senate.59th Cong., 1st sess. Vol. 40, Part 9. 1906: 8,143-8. Print. This document, another congressional record, contains the full debate on the Joint Resolution as it was passing through Congress, as well as examples of the friction caused by state and federal control, such as when a forest fire destroyed part of the land. I found it quite interesting to read the debates because I could understand the entire argument, both for and against federal jurisdiction. H.R. Rep. No. 59th Cong., 1st sess.-No.2339 (1906). Print. This report from the House of Representatives describes the dual ownership of the valley and the surrounding land as imperium in imperio – that is, a ruling within a ruling. The report also details the reasoning behind one of the eliminations of land from the valley Wentz 19 but also the protection of land under the Joint Resolution and contains the draft from 1905, before the boundary changes were made effective. Jones, Holway R. “John Muir and the Sierra Club: The Battle for Yosemite.”Map. Yosemite Online Library.Web. 6 Jan. 2012. Found in Appendix IV, this map shows the boundary changes from the park‟s creation in 1864 as a state park to the first draft of the Joint Resolution in 1905. This map was part of the Sierra Club‟s biography on John Muir and his efforts to save Yosemite from developers. This map was useful because it detailed further reforms to conservation and education of the land – even if a compromise was necessary. No. 27, 59th Cong., United States Statutes at Large (1906) (enacted). Print. This document held the full text of the final Joint Resolution from 1906, which I analyzed in my paper. Approved 11 June 1906, the resolution provided complete federal protection for Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove, as well as the oversight of the Secretary of the Interior and protection from development. “Overview Map of Yosemite Valley.”Map. Yosemite Online Library.Web. 15 Jan. 2012. This map provides a simple overview of Yosemite Valley today, including lodging, trails, and rest stops. I chose to include this in my paper as Appendix V because it documents the lasting effects the revolutionary alliance – and federal control – brought to Yosemite. Pillsbury Picture Company. Panorama of Mariposa Big Tree Grove.Circa 1906. Photograph. District of Columbia. Library of Congress.Web. 28 Dec. 2011. This photograph, found in Appendix III, shows the Mariposa Big Tree Grove in approximately 1906. Originally a very wide panoramic view of the grove, I split the photograph in two parts to adapt to the size of the paper. Like the photograph of Yosemite Valley, this source was used to show the pure beauty of the land. S. Rep. No. 3623. 59th Cong., 1st sess.-No.3623 (1906). Print. This Senate report on Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove provided excellent background information on the argument for complete federal protection, such as an increase in tourists to the park as well as the simple fact that it was unnecessary to govern one land as two separate parcels. Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir on Glacier Point, Yosemite Valley, California, in 1903. 1903. Photograph. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Library of Congress.Web. 6 Nov. 2011. This photograph, taken in 1903, depicts John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt on Glacier Point in Yosemite Valley. This camping trip proved to be a major turning point in the Wentz 20 conservation movement in the twentieth century as Muir convinced Roosevelt to provide federal protection for Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove while they were camping. This photograph can be found in Appendix I. United States. Cong. House. Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1905. 59th Cong., 1st sess. H. Rept. 5.Vol. 18. District of Columbia: Washington Government Printing Office, 1906. Web. 27 Dec. 2011. This publication contained the early stages of the Joint Resolution with some of the changes made to the Resolution along with reports from the Department of the Interior. This publication also provided me with the Sierra Club‟s argument for federal protection of the land – this argument was instrumental in the shift from state to federal control, as it contrasted the care of Yellowstone National Park with the misuse of Yosemite Valley. Secondary Sources Brinkley, Douglas. The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America. New York City: HarperCollins, 2009. Print. This source gave a wide overview of not only Roosevelt but his relationship with Muir as well. Unfortunately, I was not able to read the entire book, so this source was used to explain the duo‟s camping trip in which Muir convinced Roosevelt to provide better protection for Yosemite Valley and the adjacent Mariposa Big Tree Grove. Egan, Timothy. The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire That Saved America. New York City: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009. Print. Like The Wilderness Warrior, this source also gave an overview of the camping trip and the conversations shared by Muir and Roosevelt, especially about the timber and sheep herding industries, which were threatening Yosemite Valley‟s natural state. “Glenn Beck: February 23, 2010.” Glenn Beck. FOX News. 23 Feb. 2010. Television. Transcript. This transcript is from an episode of the Glenn Beck Program in which Beck hosted Warren Meyer, one of the nation‟s leading supporters of park privatization. I did not cite this interview in my paper; however, it lead me to Meyer‟s two websites and I gained preliminary knowledge of the park privatization movement. Greene, Linda. Yosemite: The Park and Its Resources Historic Resource Study. Rep. Vol. I. Denver: Government Printing Office, 1987. Yosemite: the Park and Its Resources Historic Resource Study. Web. 26 Nov. 2011. This study gave a narrative on the early years of Yosemite National Park, from the first grant from Lincoln to the creation of the national park in 1890. This simple source was Wentz 21 especially helpful in the early stages of my research, because Yosemite‟s history is one which can be difficult to follow. “John Muir's Influences.” National Park Service. National Park Service, 24 Jan. 2011. Web. 16 Oct. 2011. This website was one of the first sources I consulted in my research because it provided such simple background information on Muir‟s influences, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, and his relationship with Roosevelt, which proved to be revolutionary in the United States‟ conservation movement. “Losses and Gains: 1850-1900.” National Park Service.National Park Service.Web. 22 Nov. 2011. This website explained the early evolution of Yosemite National Park, starting in 1864 when President Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant, setting aside the land purely for conservation, and then in 1890 when Yosemite Valley became a national park under the Yosemite National Park Act of 1890. This was an early source in my research because of its simplicity and wide overview of the park‟s history. I referred to this website numerous times when I could not remember which legislation was passed when. Meyer, Warren. Park Privatization. Warren Meyer. Web. 19 Jan. 2012. This website, written by Meyer, gave me an overview on the practice of park privatization. Unlike Meyer‟s other website I consulted, Recreation Resource Management, this source was focused on park privatization as a whole. Meyer‟s quotes were derived from this website for the section of my paper which details the modern reaches of the alliance and the Joint Resolution. Recreation Resource Management.Recreation Resource Management.Web. 19 Jan. 2012. This website is that of Warren Meyer‟s company. Meyer is the founder of Recreation Resource Management, one of the nation‟s leading park privatization companies. I learned the very basics of park privatization from this website and was also directed to Meyer‟s other website, Park Privatization, which is more of an explanation of the practice of privatizing parks, while this website is for his company. Roa, Michael. Redwood Ed: A Guide to the Coast Redwoods for Teachers and Learners. Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods, 2007. Print. This guide, published by the Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods, a non-profit environmental organization, provides an overview of the history of coastal redwood region in California, human involvement, and the sciences relating to this particular ecosystem. I cited this source because I used a logging statistic from the guide for the 1900 in California. Wentz 22 Runte, Alfred. Yosemite: The Embattled Wilderness. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1990. Print. This source gave an overview on the opposition‟s argument for the shift to federal control and the reasoning behind why each side thought they were right – conservationists, such as the Sierra Club, believed the best protection for the land would come with federal control; however, local developers believed state control would be best for commercial enterprise and also warned of the damage to the state‟s pride which would result in the event of a power shift. “The Life and Legacy of John Muir.” Sierra Club.Sierra Club.Web. 20 Nov. 2011. This website provided a full timeline on Muir‟s life as well his lasting impact on environmentalism and the conservation movement. This was one of the first sources I consulted because of its broad scope on Muir‟s life and his contributions to protecting natural land. This timeline described Muir‟s childhood, early jobs, his time spent in college, and his conservation efforts. “Timeline: Life of Theodore Roosevelt.” Theodore Roosevelt Association. Theodore Roosevelt Association.Web. 21 Nov. 2011. Much like the timeline of Muir‟s life, this timeline was especially helpful in seeing Roosevelt‟s life as a whole, as well as how his political power contributed to his alliance with Muir. His work with the Rough Riders, the National Guard, and the New York State Assembly, among much more, were detailed in this timeline. Yosemite Natural History Association. Self-guiding Auto Tour of Yosemite National Park. Yosemite Natural History Association, 1956. Yosemite Online Library.Web. 31 Jan. 2012. This pamphlet, found online, gave me my opening quote. It was written in 1956 by Richard P. Ditton and Donald E. McHenry as a guide to touring Yosemite National Park without a ranger. It is highly detailed, with numerous directions from different entrances into the valley, points of interest (such as the campsite marker), and descriptions on the wildlife and plants in the park. “Yosemite: Park Statistics.” National Park Service.National Park Service.Web. 22 Jan. 2012. This website provided modern information on Yosemite National Park, such as infrastructure (trails, bridges, and facilities) and the total number of tourists to the park each year. I used this information while writing about the modern reaches of the alliance and Joint Resolution.