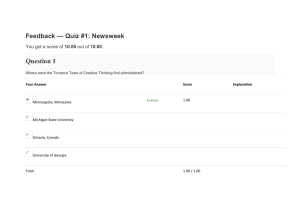

Decision Making

advertisement