Organizational Structure of College Athletics

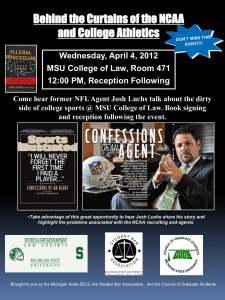

advertisement

NCAA’s Role in Regulating Intercollegiate Athletics 1840 - 1910 ✤ Intercollegiate athletics was under-regulated and a source of substantial concern, despite the shift from student control to faculty oversight and some conference regulation ✤ There were concerns regarding the need to control the excess of intercollegiate athletics ✤ In 1905 alone, there were over 18 deaths and 100 major injuries in intercollegiate football ✤ In an attempt to make the game safer, representatives of many intercollegiate football programs came together and formed the Rules Committee, which was called the Intercollegiate Athletic Association (IAA) ✤ The IAA became the NCAA in 1910 01 NCAA’s Role in Regulating Intercollegiate Athletics 1910 - 1970 ✤ NCAA began to stretch its role from merely making rules for football and other games and also began creating national championship events in various sports ✤ In the 1920s, public interest in sport at the intercollegiate level continued to increase in intensity ✤ College sports were becoming commercialized ✤ NCAA tried to restructure rules to increase integrity in the governance of intercollegiate athletics, those efforts were insufficient to keep pace with the growing commercialization of, and interest in, intercollegiate athletics ✤ After WWII, more colleges and universities started athletic programs, while others expanded existing programs, in an effort to respond to increasing interest in intercollegiate athletics 1971 - 1983 ✤ In the early 1970s, the NCAA created divisions ✤ In 1976, NCAA was given the authority to penalize schools directly ✤ Schools became fearful of the NCAA as enrolments dropped and expenses increased. They also realized that reputations were tied to the athletic programs NCAA’s Role in Regulating Intercollegiate Athletics 1984 - 1999 ✤ College presidents formed the influential Presidents Commission in response to pressures from the board of trustees and alumni who demanded winning athletic programs and educators who feared the rising commercialization of athletics and its impact on academic values ✤ The Presidents Committee reviewed the NCAA enforcement and infractions process and named one of their own as Chairman ✤ NCAA once handled the televising rights of football programs for their schools until the Supreme Court held that the NCAA had violated antitrust laws. Rights were given to schools to directly reap revenues from televised games ✤ Developments during the past two decades have focused on governance and economic issues ✤ There have been some efforts, however, to enhance academic integrity and revitalize the role of faculty and students in overseeing intercollegiate athletics 01 NCAA’s Role in Regulating Intercollegiate Athletics The one certainty in the future of the NCAA is the likelihood that big-time intercollegiate athletics will be engaged in the same point-counterpoint that has characterized its history; increased commercialization and public pressure leading to more sophisticated rules and regulatory systems Applying Antitrust Law to NCAA Regulation of “Big Time” College Athletics ✤ The purpose of intercollegiate athletics was to provide an extracurricular activity for talented students who attended college primarily to earn an academic degree that would enable them to pursue a career outside of professional athletics ✤ According to the NCAA, student athletes shall be amateurs in an intercollegiate sport, and their participation should be motivated primarily by education and by the physical, mental and social benefits to be derived 01 Applying Antitrust Law to NCAA Regulation of “Big Time” College Athletics ✤ The public popularity of men’s college football and basketball creates a substantial revenuegenerating capacity and the prospect of increased visibility for universities ✤ The NCAA seeks to: 1) preserve the amateur nature of college sports; 2) preserve sport as a component part of higher education; and 3) ensure competitive balance on the playing field ✤ Given the economic realities of “big-time” college athletics, many NCAA rules limiting economic competition among universities appear to violate the federal antitrust laws ✤ Courts initially held that NCAA rule-making, regulatory, or enforcement activities do not sufficiently impact interstate trade or commerce to establish Sherman Act jurisdiction. NCAA rules designed to promote amateurism and protect academic integrity were deemed to constitute regulation of noncommercial activity that does not trigger antitrust scrutiny ✤ In 1984, the Supreme Court held that the NCAA does not have a blanket exemption from the antitrust laws, although it is a nonprofit entity with educational objectives, because the NCAA and its member institutions are in fact organized to maximize revenues. As a result the court invalidated the NCAA’s control over the sale of television rights to games (NCAA v. Board of Regents) Applying Antitrust Law to NCAA Regulation of “Big Time” College Athletics ✤ NCAA rules to preserve amateurism, academic integrity, and competitive balance do not violate the antitrust laws ✤ NCAA rules are ancillary noncommercial restraints necessary to produce intercollegiate athletics and/or to further legitimate higher education objectives ✤ Courts have rejected antitrust challenges to NCAA regulations designed to preserve the amateur nature of college sports, such as the “no draft” and “no agent” rules and the imposition of disciplinary sanctions on institutions for violation of the NCAA’s amateurism rules ✤ Courts have also concluded that the NCAA’s rule restricting the size of manufacturer logos on uniforms has no significant anticompetitive effect as a matter of law ✤ The author believes courts should abandon anachronistic precedent based on unrealistic ideals of the “amateur” nature of “big-time” college athletics and develop a principled antitrust jurisprudence more consistent with the economic realities of college sports in the 21st century Applying Antitrust Law to NCAA Regulation of “Big Time” College Athletics NCAA regulation that has anticompetitive, intrabrand effects should be proven to be the least restrictive means of promoting interbrand competition as a matter of fact, rather than being presumed to do so as a matter of law Restoring Educational Primacy to College Basketball Organizational Structure of College Athletics: ✤ NCAA requires university presidents to assume the responsibility for athletics programs ✤ University presidents appoint athletics directors who bear the burden for assuring that the athletics department’s goals remain consistent with the overall purpose of the university ✤ University presidents also delegate responsibilities for their athletic programs to collegiate conferences ✤ NCAA is the leading regulatory body for intercollegiate athletics 01 Restoring Educational Primacy to College Basketball Threats to Educational Primacy ✤ College athletics plays a role in increasing the institution’s visibility and also generates revenues from a variety of sources A. Competitive Pressure: ✤ A winning team increases a coach’s job security and base salary ✤ Pressure to win usually manifests itself in ways that seriously conflict with the principle of educational primacy ✤ Only 43% of all NCAA basketball players graduate within 6 years ✤ Wild card admissions process gives a coach a limited number of “no questions asked” admits ✤ NCAA limits an athlete’s participation in “countable athletically related activities” to 4 hours/day and 24 hours/week but some athletes complain that voluntary workout exception swallows this rule so athlete’s can still spend 40-60 hours/week on their sport ✤ Often times, student-athletes must choose between athletic success and academic success B. Commercialism: ✤ The commercial model of college athletics gives priority to the spectators’ entertainment needs, rather than to student-athletes’ educational needs ✤ Dependence on revenues from gate receipts, corporate sponsorships, and television contracts intensifies external pressures to win ✤ Commercialism raises concerns of financial exploitation for student-athletics Restoring Educational Primacy to College Basketball C. Professionalism ✤ The athletic scholarship can be viewed as a manifestation of the professionalism that characterizes “amateur” college athletics ✤ Student-athletes cannot withdraw from their sports, even for academic reasons, without suffering detrimental economic consequences of such a decision 01 Restoring Educational Primacy to College Basketball Governance of the Principle Educational Primacy A. Internal Governance (universities, conferences, and the NCAA) ✤ Regulate both the economic and educational aspects of intercollegiate athletics ✤ Universities are ideal entities to police the principle of educational primacy, however they have not adequately done this ✤ Conferences and the NCAA are financially dependent on activities that compete with the principle of educational primacy and cannot be expected to vigorously police or enforce the principle of educational primacy ✤ Self-interest and conflicting goals have prevented all 3 internal governance structures from adequately policing the principle B. External Governance (legislature and courts) ✤ Courts & legislature have chosen to take a passive role in the regulation of college athletics ✤ By being passive, the courts have given NCAA virtually unlimited power over the future of college athletics Restoring Educational Primacy to College Basketball Therefore, the NCAA is in a unique position to strengthen the principle of educational primacy yet any attempt to strengthen educational primacy must also minimize its major threats. The NCAA should ensure that future legislative amendments do not further weaken the principle Ross v. Creighton University Facts: ✤ Ross accepted an athletic scholarship to attend Creighton University and play basketball ✤ Ross was below the academic level at Creighton but he was assured that he would receive sufficient tutoring so that he would receive a meaningful education ✤ Ross attended Creighton for 4 years and maintained a D average ✤ After Ross’s four years at the school, he only acquired 96 of the 128 credits needed to graduate and Ross had language skills of a 4th grader and reading skills of a 7th grader ✤ Ross alleges that the athletic department advised him to take easier classes that did not count towards a university degree and that Creighton failed to provide him with sufficient and competent tutoring that it had promised Kevin Ross at Westside Preparatory School 01 Ross v. Creighton University Issue: Whether Ross’s complaint states a claim under Illinois law Negligence: 1. Educational Malpractice ✤ Policy concerns counsel against allowing claims for educational malpractice ✤ Lack of satisfactory standard of care by which to evaluate an educator ✤ Inherent uncertainties exist in this type of case about the cause and nature of damages ✤ Potential flood of litigation ✤ The Illinois Supreme Court would refuse to recognize the tort of educational malpractice 2. Negligent Admission ✤ Illinois would reject this claim for same policy reasons as above ✤ Cause of action would present difficult problems to a court attempting to define a workable duty of care ✤ Cause of action might interfere with a university’s admissions decisions, to the detriment of students and society as a whole 3. NIED ✤ Ross argues Creighton wrongfully admitted him and then caused him emotional harm ✤ For the same policy reasons as above, Illinois would refuse to recognize in this situation a claim for NIED Ross v. Creighton University The Contract Claims: ✤ Ross alleges that Creighton breached an oral or written contract it had with him ✤ A contract between a private institution and a student confers duties upon both parties which cannot be arbitrarily disregarded and may be judicially enforced ✤ A decision of the school authorities relating to the academic qualification of the students will not be reviewed ✤ Courts are not qualified to evaluate the attainments of a student and courts will not review a decision of the school authorities relating to academic qualifications of the students ✤ Ross alleges that the University knew that he was not qualified academically to participate in its curriculum and made a specific promise that he would be able to participate in a meaningful way because of the special services promised to him 01 Ross v. Creighton University The court ruled that the district court can adjudicate Mr. Ross's specific and narrow claim that he was barred from any participation in and benefit from the University's academic program without second-guessing the professional judgment of the University faculty on academic matters English v. NCAA Facts: ✤ Plaintiff wanted to play football at Tulane University and thus jumped around from college to college in order to get a better chance of being accepted to Tulane ✤ The Plaintiff was barred from playing under an eligibility rule that states a player cannot play in back to back seasons with a different school Plaintiff alleges: 1. He was denied due process 2. The NCAA's actions were capricious, arbitrary, unfair, and discriminatory Iowa State Cyclones 1979 - Jon English is number 15 01 English v. NCAA 1. Due Process: ✤ Plaintiff claims he was not adequately informed of the rules regarding his eligibility ✤ However, testimony from plaintiff’s father, an NCAA coach, showed that the plaintiff was well aware of the underlying and laudable policy of the NCAA to prevent a student from playing for two different colleges in successive years ✤ The rule deals with a present college attempting to certify a player as eligible when he has played for a previous college 2. Was the NCAA arbitrary, capricious, unfair, or discriminatory towards plaintiff? ✤ There is no evidence to support the plaintiff’s contention ✤ Had he inquired of the NCAA as to his plans before he left Iowa State he would have been told that he could not play at another college in 1983 English v. NCAA The plaintiff had every opportunity to prove his case and he failed to convince the court that he was entitled to further injunctive relief Bloom v. NCAA Facts: ✤ The University of Colorado recruited Bloom to play football ✤ Before enrolling, Bloom competed in Olympic and professional World Cup skiing events, becoming a World Cup champion in freestyle moguls ✤ Bloom appeared on MTV, and had various paid entertainment opportunities. He also endorsed ski equipment and contracted to model clothing for Tommy Hilfiger ✤ CU requested waivers of NCAA rules restricting student-athlete endorsement and media activities and, then, a favorable interpretation of the NCAA rule restricting media activities ✤ The NCAA denied CU’s request, Bloom discontinued his endorsement, modeling, and media activities Bloom alleged: 1. As a third-party beneficiary of the contract between the NCAA and its members, he was entitled to enforce NCAA bylaws permitting him to engage in and receive remuneration from a professional sport different from his amateur sport 2. As applied to the facts of this case, the NCAA's restrictions on endorsements and media appearances were arbitrary and capricious 3. Those restrictions constituted improper and unconscionable restraints of trade Bloom v. NCAA Interpretation of NCAA Bylaws ✤ To determine the intent and expectations of the parties, we view the contract in its entirety. If its meaning is clear and unambiguous, the contract is enforced as written ✤ NCAA Bylaw states that a professional athlete in one sport may represent a member institution in a different sport ✤ Bloom asserts that a professional is one who gets paid for a sport and argues that a student-athlete is entitled to earn income that is customary from his professional sport ✤ The NCAA bylaws express a clear and unambiguous intent to prohibit student-athletes from engaging in endorsements and paid media appearances, without regard to: (1) when the opportunity for such activities originated; (2) whether the opportunity arose or exists for reasons unrelated to participation in an amateur sport; and (3) whether income derived from the opportunity is customary for any particular professional sport 01 Bloom v. NCAA Application of Bylaws to Bloom ✤ Paid entertainment activity may impinge upon the amateur ideal if the opportunity were obtained or advanced because of the student's athletic ability or prestige, even though that activity may further the education of student-athletes such as Bloom, a communications major ✤ Bloom presented evidence that some of his acting opportunities arose not as a result of his athletic ability but because of his good looks and on-camera presence ✤ However, Bloom was marketed as a talented multi-sport athlete and that Bloom’s reputation as an athlete would be advantageous in obtaining auditions for various entertainment opportunities ✤ The financial benefits from commercially endorsed athletic equipment by having students wear equipment with logos while competing has a rational basis in economic necessity since the financial benefits inure not only a single student-athlete but to member schools and other athletes ✤ Bloom failed to demonstrate any inconsistency in application of the NCAA Rules and hence failed to prove the NCAA was arbitrarily applying its rules Bloom v. NCAA Bloom failed to demonstrate a reasonable probability of success on the merits