state benefits under the pike balancing test of the dormant

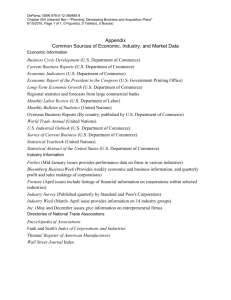

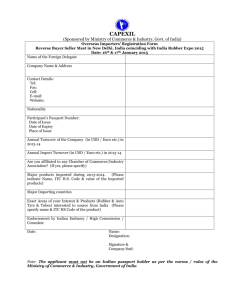

advertisement