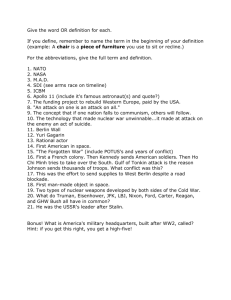

6 May 2012 – Isaiah Berlin's “Two Concepts of Liberty”

advertisement

Isaiah Berlin’s “Two Concepts of Liberty” Liberty as Political Freedom In today’s session we shall be talking about “liberty”, which modern philosophers often also refer to as “political freedom”. The campaigning group “Liberty” lists the following in its charter as some aspects of political freedom: • • • Tahrir Square, 2011 “At last, a free country” • • • • • • • safety from personal harm; protection from ill treatment or punishment that is inhuman or degrading; equality before the law and freedom from discrimination on such grounds as disability, political or other opinion, race, religion, sex or sexual orientation and marital status; protection from arbitrary arrest and unnecessary detention; a fair hearing before any authority exercising power over the individual; freedom of thought, conscience and belief; freedom of speech and publication; freedom of peaceful assembly and association; move freely within one's country of residence and to leave and enter it without hindrance; privacy and the right of access to official information As philosophers we want to sharpen our understanding of political freedom in all these contexts, and others. What are we getting at when we talk about political freedom, and what kinds of assumptions and values are involved in the ways people use the idea? Isaiah Berlin (1909-1997) One of the most influential attempts to answer these questions is Isaiah Berlin’s “Two Concepts of Liberty”, which was delivered as a lecture at Oxford in 1958. Berlin was a renowned historian of ideas and man of letters, with a formidably wide range of intellectual interests. Born into a wealthy Russian-Jewish family in 1909, he came to the UK from Russia in 1921, after the Revolution of 1917 and the creation of a communist state. Berlin returned to the Soviet Union immediately after World War II, working for the British Foreign Office. During this period he was in contact with “dissident” writers such as Anna Akhmatova and Boris Pasternak; he famously organised the smuggling out to the West of Pasternak’s novel Doctor Zhivago. His experience of the USSR helped to convince him of the importance of political freedom, not least because the actions of the Soviet regime were carried out in the name of “Liberty”. It is worth thinking about how the argument of “Two Concepts of Liberty” relates to the struggle between capitalism and communism in the Cold War. Negative Freedom The first “concept of liberty”: Political freedom is doing whatever you want, without interference. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan ch.21 (1651) “A free man is he that…is not hindered to do what he has a will to.” This is liberty defined as the lack of anything to hinder an agent’s action, e.g. obstruction by political authorities. Philosophers call it a “negative” conception, because it is defined in terms of an absence (external interference with action). The less that is preventing you from doing what you want to do in a given situation, the more you can be said to be free. By contrast, the “positive” conception of freedom involves the question of who, or what, is in control of a person’s actions. The more that a person is in control of what he or she does, the greater his or her freedom – more on this later. The idea of negative freedom seems to capture the non-judgmental aspect of political liberalism. It doesn’t matter what your desires are; whether you want to discuss philosophy, play tiddly winks, or just loaf around all day, if there is some external factor preventing you from doing so, then in that respect you are unfree. However, even philosophers who explain freedom negatively have recognised that untrammeled freedom would lead to a dire situation where people would be at liberty to do terrible things to each other. The problem for political theory is to find some way to constrain people’s actions so that they can live together, which minimises the impact on their freedom. One famous attempt to specify a bare limit to negative freedom was John Stuart Mill’s “harm principle”: “the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.” On the other hand, because the idea of negative freedom in its purest form is only concerned with external circumstances (as long as you can do what you want, you are free) we get some odd outcomes. For example, imagine a slave-owner who allows her slaves to do whatever they like. Imagine also, that her slaves have no thought of running away – perhaps they are happy, well-fed, entertained, and so on. We would not usually consider such people to be free, and yet that is what the pure idea of negative freedom indicates. More generally, we can say that the idea of negative freedom paradoxically gives us a reason to accommodate ourselves to our circumstances. Since freedom is about not having our will obstructed, we can always increase it by relinquishing desires that are likely to be frustrated. Berlin calls this “the retreat to the inner citadel” (also “the doctrine of sour grapes”), and sees it as a serious problem with negative freedom. Positive Freedom The second of Berlin’s concepts of liberty involves an idea of selfmastery: Political freedom is being in control of your life. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile, Bk 5 (1761) Up to now you were only apparently free. You had only the precarious freedom of a slave to whom nothing has been commanded. Now be really free. Learn to become your own master. Command your heart, Emile, and you will be virtuous. On the negative conception, the slave can become free by reducing his desires until he is happy with his situation. Proponents of the positive conception, on the other hand, say that you cannot increase your freedom just by shrinking or warping your desires, and therefore by shrinking or warping your self. Freedom involves being your own master, rather than someone or something else controlling you; in other words, your actions as a free person express your true self. Consider the case of a nicotine addict, with a compulsion to smoke cigarettes. According to the idea of negative freedom, as long as she is able to indulge her habit, then she is free. By contrast, a defender of positive freedom would object that the person is not truly free, because she is in the grip of a compulsion and not making a choice with which she can identify. How does this conception of freedom translate into politics? Political life is something of a problem for defenders of the positive conception of freedom, because it seems that in order to associate with other people, we have to give up a bit of control over our lives – for instance, we have to obey certain rules that govern our interactions with other citizens. However, defenders of positive freedom have argued that, according to their conception of liberty, the existence of laws should not be interpreted as a limitation on our freedom, as under the negative conception. On the contrary, so far as we can identify with the process that decides the laws, they can be seen as a way in which we extend control over our lives. By conforming to the laws we are increasing our own and others’ freedom. The positive conception of liberty assumes that freedom is not an easy matter. For one thing it requires us to be the best people we can be, which, as Berlin points out, usually involves a difficult process of overcoming our vices or other inadequacies. In other words, the positive conception includes an assumption that people are divided against themselves, and that this is a problem to be overcome. At the same time, the positive conception also requires of us that we identify closely with the political process. It is only by taking to heart the idea that the laws express everyone’s attempts at being their own master that I can truly consider myself a free citizen. The upshot of this is that we may need to challenge ourselves and other people in order to make sure we live continue to live together as free citizens in a free society; think of how we become concerned if people are too apathetic to vote in an election, or if our representatives behave corruptly, and so on. Because the ideal of positive freedom often requires us to confront our political circumstances, Berlin claims, it has been a motivating factor for many revolutionary movements (e.g. in France and Russia). This is a different emphasis from negative freedom, which, as we have seen, might lead us to become accommodated to our circumstances, so long as a basic core of personal space is protected. However, Berlin worries the ideal of positive freedom might, paradoxically, impel revolutionary movements to become totalitarian. Suppose we are unwilling or unable to live up to the standards upheld by those in power; doesn’t this give the authorities a motivation for intervening to make us conform to their conception of good citizenship? The anxiety is that people might be forced into doing things against their actual wishes, because, it is claimed, this is what their “true” selves would desire. More subtly, Berlin also objects to the idea of positive freedom because it is monolithic; it assumes (or so he thinks) there is one system of values to which we should all aspire. By contrast, negative freedom is more consistent with the idea of value pluralism: the belief, as Berlin puts it, that “human goals are many, not all of them commensurable, and in perpetual rivalry with one another”. Further Questions Are two concepts of liberty are enough to understand the uses of the term? How important or useful is the distinction? Some philosophers have argued that whenever we talk about political freedom, we always have a sense of someone being free from constraints to do something – this seems to combine positive and negative conceptions. On the other hand, perhaps the different kinds of liberty have a “family resemblance”, but ultimately cannot be reduced to one or two ideas. We might also ask how the different conceptions of liberty relate to other ideals, like knowledge, justice or equality. How does liberalism relate to feminism, or nationalism? Berlin seems to prefer negative liberty (with qualifications) on the grounds that it supports value pluralism. But isn’t he rather helping himself to the idea that the conflict of incommensurable values is perpetual? That seems to deny the possibility of progress towards the truth in discussions about values. References and Suggested Reading The text of “Two Concepts” can be found in a collection of Berlin’s writing called Liberty, edited by Henry Hardy (2002). It’s also available online: do a Google search on “Isaiah Berlin liberty full text”. For a summary of his work see the article on Berlin in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/berlin/) this is a great general resource, by the way, and it’s free! There are some good biographies of Berlin, e.g. by Michael Ignatieff. John Gray’s Isaiah Berlin (1995) contains a strong response to the idea that value pluralism and liberalism go together. The idea of political freedom is very much a “hot topic” in philosophy, e.g. Phillip Pettit’s book Republicanism (1997). For more background reading, see the article on “Positive and Negative Liberty” in the Stanford Encyclopedia (http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/liberty-positive-negative/).