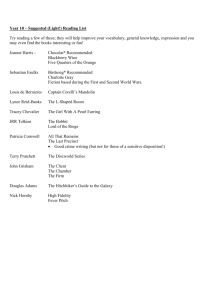

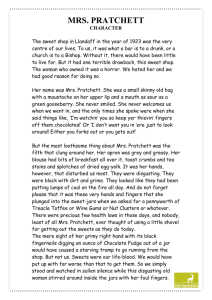

Translation of Parodies in Terry Pratchett's Witches Abroad and

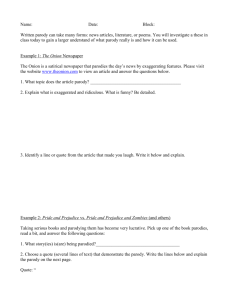

advertisement