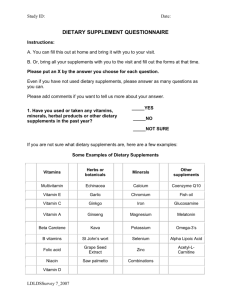

Supplements Who needs them?

advertisement