Hammer v. Dagenhart

advertisement

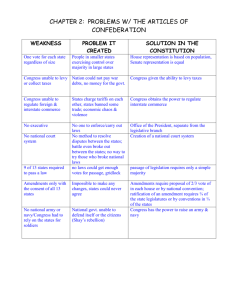

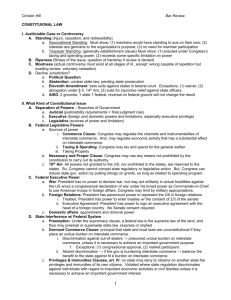

Hammer v. Dagenhart v. (Not Stated) 247 U.S. 251 , 38 S.Ct. 529 (1918) (Not Stated) CONGRESS MAY NOT USE THE COMMERCE POWER AS A PRETEXT FOR REGULATING EMPLOY­ MENT CONDITIONS WITHIN THE STATES . • INSTANT FACTS A father wanting to put his two minor children to work in a cotton mill is suing on the ground that Congress' use of the commerce power to regulate child labor in the states by blocking the interstate transportation of child-made goods is unconstitutional. • BLACK LETTER RULE The commerce power does not allow Congress to regulate in areas traditionally left up to the states' police power, such as the area of child labor laws. • PROCEDURAL BASIS Appeal to the Supreme Court after a bill was filed in federal district court seeking an injunction against enforcement of a federal law blocking interstate commerce in goods produced by child labor. • FACTS Congress passed a law prohibiting the transportation in interstate commerce of goods manufactured in factories employing children under the age of fourteen, or between fo Jrteen and sixteen , depending upon the number of hours these children were allowed to work. A fath~ r (P) seeking to put his two children to work seeks an injunction against enforcement of the law 011 the ground that it oversteps Congress' commerce power . • ISSUE May Congress rely on the Commerce Clause in attempting to regulate local activities, such as child labor, by prohibiting the interstate transportation of goods manufactured through such local activities? I • DECISION AND RATIONALE (Day, J) No. The thing intended to be accomplished by this statute is the denial of the facilities of interstate commerce to manufacturers who employ children within the prohibited ages , It does not, in its effect, regulate transportation among the states, but aims to set a national standard for the employment of children . The goods shipped are, of themselves, harmless. When offered for shipment, the labor of commerce transportatheir production is over, and the mere fact that they were intended for interstate I tion does not make their production subject to federall control under the commerce power. Tne production of articles intended for interstate commerce is a matter df local regulation. When the commerce begins is determined by its actual delivery to a common ca'rrier for transportation , or the actual commencement of its transfer to another state, If it were otherwisd, the states would be left with no authority over its local manufacturing concerns. It is asserted that tlhe legislation is constitutional because it seeks to insulate from unfair competition other states where the evil of child labor has been recognized . There is, however, no power vested in Congress to requir1e the states to exercise their police power so as to prevent possible unfair competition. The grant to Congress of power over the . subject of interstate commerce enab'led it to regulate such commerce, find not to give it authority. to control the states in their exercise of the police power over local tr~de and manufacture. Police ! HIGH COURT CASE SUMMARIES . 77 Hammer v. Dagenhart (Continued) regulations relating to the internal trade and affairs of the states have been uniformly recognized as within such state control. That regulation of child labor is an important issue is shown by the fact that every state has such regulations. But it is up to the states, not the federal government, to decide what regulation it needs and such regulation should be implemented. An opposite holding would sanction an invasion by the federal power of the control of a matter purely local in its character. The act is thus repugnant to the Constitution in two ways. It not only transcends the authority delegated to Congress over commerce, but also exerts a power as to a purely local matter to which the federal authority does not extend. To allow such a law to stand would practically destroy our system of government. • DISSENT (Holmes, J) If an act is within the powers specifically conferred upon Congress, it seems to me that it is not made any less constitutional because of the indirect effects that it may have, however obvious it may be that it will have those effects, and that we are not at liberty to hold it void upon such grounds. The statute in question is within the power expressly given to Congress if considered only as to its immediate effects and that, if invalid, it is so only upon some collateral ground. The statute confines itself to prohibiting the carriage of certain goods in interstate commerce. Congress is given power to regulate such commerce in unqualified terms. The power to regulate most assuredly includes the power to prohibit. I should have thought that the most conspicuous decisions of this Court had made it clear that the power to regulate commerce and other constitutional powers could not be cut down or qualified by the fact that it might interfere with the carrying out of the domestic policy of any state. The propriety of the exercise of a power admitted to exist should be for the consideration of Congress alone, without intrusions by this Court. Congress has the power to regulate the transportation of goods across state lines. This it did. Its motivation should not be part of the inquiry. Analysis: This case is a perfect example of congressional attempts to stop the "race to the bottom," where individual states, in order to provide themselves w.ith a competitive advantage over other states, adopt a laissez faire approach to business and industry. By adopting child labor laws that are less restrictive than those of other, especially surrounding, states, a state makes it cheaper to do business within its borders. This principle can be seen in the context of environmental laws. Over the last third of the twentieth century, the state and federal governments began adopting more stringent environmental protection laws. Obviously, an industry that pollutes heavily, and thus incurs more costs in cleanup and pollution prevention, will save money by relocating to a state with less stringent pollution control laws. Many jurisdictions may be inclined to relax their laws in order to attract these industries, along with their concomitant jobs and tax base. To compete, other states are then forced to do the same. This is where the federal government's race to the bottom argument for a national minimum standard comes into play. In Hammer, the Court refused to buy this argument , though it had, and would , buy it in the past and future. United States v. Darby (Government) v. (Lumber Producer) 312 U.S. 100, 61 S.Ct. 451 (1941 ) SUPREME COURT EXPRESSLY OVERRULES HAMMER V. DAGENHART -. _ I ! ~ ~: • INSTANT FACTS A Georgia lumber company violated federal minimum wage/maximum hour laws . Its defense is that the federal government overreached its Commerce Clause authority in setting the standards. • BLACK LETTER RULE Congress has the au­ thority, under the Commerce Clause, to exclude any article from interstate commerce, in judg­ ment that they are injurious to the public health, morals or welfare. l G1 'fl' ) ( r A) Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States (Discriminating Mote~ v. (Government) 379 U.S. 241, 85 S.Ct. 348 (1964) RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN PUBLIC ACCOMMODATIONS .EXERTS A SUBSTANTIAL AND HARMFUL EFFECT UPON INTERSTATE COMMERCE • INSTANT FACTS An Atlanta, Georgia motel wishes to continue its racially discriminatory op­ erations in spite of the 1964 Civil Rights Act (Act) barring racial discrimination in public accommo­ dations. • BLACK LETTER RULE Congress has the power, under the Commerce Clause, to regulate local activities that could reasonably be seen as exerting a substantial and harmful effect upon interstate commerce. • PROCEDURAL BASIS Declaratory judgment action appealed to the Supreme Court after a lower federal court issued an injunction prohibiting violation of the Act. • FACTS Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Act) in order to ban racial discrimination in public accommodations. Testimony .in support of the Act included evidence that such racial discrimination has the effect of making it much more difficult for racial minorities to find lodging and other accommoda­ tions while traveling from state to state. Further, that this has the concomitant effect of dissuading minorities from traveling interstate, which results in a substantially harmful effect on interstate commerce . as a whole. In response to the Act, the Heart of Atlanta Motel (Heart) (P) filed a declaratory judgment action attacking the Act's constitutionality on the ground that it is beyond the federal commerce power. The case is before the Court on admissions and stipulations, some as follows: Heart (P) is a 216 room motel, readily accessible from two interstate highways and two state highways. Heart (P) advertises nationally; maintains over 50 billboards and highway signs within Georgia; approximately 75% of its guests are from out of state. Prior to the Act, Heart (P) refused to let rooms to Negroes, and it wishes to continue to follow this practice and, therefore, filed this suit. • ISSUE May Congress exercise the commerce power by regulating local activities that are seen as exerting a substantial and harmful effect on interstate commerce? • DECISION AND RATIONALE (Clark, J) Yes. Our study of the legislative record brings us to the conclusion that Congress possessed ample power to pass the provisions of the Act at issue herein . The record of the Act's passage in each house is replete with evidence of the burdens that racial discrimination places upon interstate commerce: that our people have become increasingly mobile, with millions of people traveling from state to state; that Negroes in particular have been the subject of discrimination in transient accommo­ dations; that these conditions had become so acute as to require the listing of available lodging for Negroes in a special guidebook. These exclusionary practices were found to be nationwide. The testimony indicated a qualitative as well as quantitative effect on interstate travel by Negroes. There was HIGH COURT CASE SUMMARIES 87 Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States (Continued) also evidence that these conditions stemming from racial discrimination had the effect of discouraging travel on the part of a substantial portion of the Negro community. Congress has often dealt with this interest in protecting interstate commerce. [The Court lists a number of Commerce Clause cases.] That Congress was legislating against moral wrongs in many of these areas rendered its enactments no less valid. Here, Congress was dealing with a moral problem. But this does not detract from the overwhelming evidence of the harmful effects of racial discrimination upon interstate commerce. It was this burden which empowered Congress to enact appropriate legislation. It is said that the operation of the motel here is of purely local character. Even if this were true, if it is interstate commerce that feels the pinch, it does not matter how local the operation which applies the squeeze. Thus, Congress may regulate the local incidents of interstate commerce, including within the states of origin and destination, which might have a substantial and harmful effect upon that commerce. We, therefore, conclude that the action of the Congress in the adoption of the Act as applied here to a motel which concededly serves interstate travelers is within the power granted it by the Commerce Clause of the Constitution. The means of removing obstacles to interstate commerce are up to Congres_s, with one caveat, that the means chosen by it must be reasonably adapted to the end permitted by the Constitution. We cannot say that its choice here was not so adopted . • CONCURRENCE (Douglas, J.) Though I concur, I am somewhat reluctant here, to rest solely on the Commerce Clause. It is may belief that the right of people to be free of state action that discriminates against them because of race occupies a more protected position in our constitutional system than does the movement of cattle, fruit, steel and coal across state lines. The result reached by the Court is much more obvious when the facts are :considered under the Fourteenth Amendment. For this Amendment deals with the constitutional status of the individual, not with the impact on commerce of local activities or vice versa. A decision based on the Fourteenth Amendment would have a more setting effect, dOing away with much litigation surrounding these issues than is instigated under the Commerce Clause. Such a construction would put an end to all obstructionist strategies and finally close one door on a bitter chapter in American history. Analysis: The Court's opinion in Heart of Atlanta is well reasoned, at least partially due to the testimony Congress took when conSidering the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Congress knew the bar it had to meet in order to make the legislation constitutional, just as it surely knew the speed with which the Act would be challenged . The Act's constitutionality here flows from the fact that an inability to rely on finding accommodations while traveling from state to state is a substantial obstruction to the undertaking of such travel. When a significant percentage of the population is much less likely to travel interstate, even the purely economic ramifications are easy to recognize. People who travel spend money in local economies, without acting as a drain on public resources. A traveler is, therefore, someone who pays without also taking. Interestingly, had civil rights not been on just-assassinated president John F. Kennedy's legislative agenda, the Act may not have passed at all, but his successor, Lyndon Johnson, made a strong moral case for passing the agenda as a way of honoring JFK's memory. 88 HIGH COURT CASE SUMMARIES (cit') (Ot A) United States v. Lopez (Government) v. (Criminal Defendant) 514 U.S. 549 , 115 S.Ct. 1624 (1995) GUN-FREE SCHOOL ZONES ACT OF 1990 DECLARED AN UNCONSTITUTIONAL EXERCISE OF THE COMMERCE POWER • INSTANT FACTS A 12th-grade student was convicted of violating the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990, which makes it a federal offense to possess a gun near a school. • BLACK LETTER RULE Congressional authori­ ty to regulate pursuant to the Commerce Clause extends to only those activities that rationally implicate (1) the channels of interstate com­ merce; (2) the instrumentalities of interstate com­ merce; or (3) activities having a substantial effect upon interstate commerce. • PROCEDURAL BASIS Appeal to the Supreme Court from the circuit court's reversal of a criminal conviction . • FACTS Congress passed the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990 (Act or § 922), making it a federal offense "for any individua'i knowing'ly to possess a firearm at a place that the individual knows, or has reasonable cause to believe, is a school zone." A "school zone" is on the grounds of or within 1,000 feet of a school. The Act neither regulates a commercial activity nor contains a requirement that the possession be connected in any way to interstate commerce. Lopez (D), a 12th-grade student, was convicted of violating the Act by carrying a concealed .38-caliber handgun and five bullets into his high school. • ISSUE Does the commerce power extend to regulation of activities having only a potential attenuated and distended effect upon interstate commerce? • DECISION AND RATIONALE (Rehnquist, C.J.) No. The Constitution ' mandates a division of authority, which was adopted by the framers to ensure protection of our fundamental liberties. A healthy balance of power between the States and the Federal Government reduces the risk of tyranny and abuse from either front. [The Court reviewed a series of Commerce Clause decisions from Gibbons to the 1940s.] These decisions greatly expanded the authority of Congress. This doctrinal change partially reflects a view that earlier Commerce Clause cases artificially had constrained the authority of Congress to regulate interstate commerce. But even these modern expansions confirm that this power has outer limits shaped by the requirements of our dual federalist system . These limits require that there be some rational basis for concluding that a regulated activity suffiCiently affects interstate commerce in order for the regulation to be valid. Consistent with this, we have identified three broad categories of activity that Congress may regulate under its commerce power. First is the use of the channels of interstate commerce. Second are the instrumentalities of interstate commerce. Third, Congress has the power to regulate those activities H I G HC 0 U R T CAS E SUM MAR I E S 97 United States v. Lopez (Continued) having a substantial relation to interstate commerce , i.e. those activities that substantially affect interstate commerce. We now consider § 922 in light of this framework. The first two categories above are not implicated here, so if § 922 is to be sustained,it must regulate an activity that substantially affects interstate commerce . In other words, where economic activity substantially affects interstate commerce, legislation regulating that activity will be sustained . The Act is a criminal statute that by its terms has nothing to do with " commerce ." The Act is not an essential part of a larger regulation of economic activity. Further, the Act contains no jurisdictional element which would ensure, through case­ by-case inquiry, that the firearm possession in question affects interstate commerce. When we look to congressional findings supporting any asserted effects on commerce we find none. The government (P) · concedes that neither the statute nor its legislative history contain[s] express findings regarding any effects on commerce of gun possession in a schoo l zone. In the courts, the government (P) arg ues that such firearm possession may result in a violent crime, which could affect the national economy in two ways. First, by imposing high financial costs upon society through insurance. Second, that violent crime dissuades individuals to travel into areas within the country where it occurs. The last argument is that guns threaten the learning environment, which handicaps the educational process. This, in turn , would have an adverse effect on the nation's well being. As a result, the government (P) argues, Congress could rationally have concluded that the Act substantially affects interstate commerce . Under the "violent crime" rationale, the commerce power would extend not only to all violent crime, but also to any activities that could lead to violent crime. Similarly, the "national productivity" reasoning would allow Congress to regulate any activity that it found was related to the economic productivity of individual citizens, such as family law. Under these theories, it is difficult to perceive any limitation on federal power. For example, if Congress can regulate activities adversely affecting the learning environment, then , a fortiori , it can also regulate the educational process directly. Admittedly, a determination whether an intrastate activity is commercial or noncommercial may in some cases result in legal uncertainty. But the Constitution mandates this uncertainty by withholding from Congress a . plenary police power that would authorize enactment of every type of legislation. While these are not, and cannot be, precise formulations , we think they point the way to a correct decision in this case. Possession of a gun in a local school zone is in no sense an economic activity that might, through repetition elsewhere, substantially affect any sort of interstate commerce. It is true that some of our prior cases have taken long steps down that road , giving grea~ deference to congressional action, but we decline here to proceed any further . • CONCURRENCE (Kennedy, J) Our struggle to define the extent to which the commerce power as our nation has changed, Counsels great restraint before the Court invalidates a congressional act under the Clause. With this pause, I join the Court's opinion with the following observations on its hol'ding . The history of our Commerce Clause jurisprudence teaches at least two lessons. First is the imprecision of content­ based boundaries used without more to define the limits of the Commerce Clause. Second, and related, is that the Court has an immense stake in the stability of our Commerce Clause jurisprudence as it has evolved to this pOint. Stare decisis operates with great force in counseling against our disturbing the essential principles now in place respecting the commerce power. Also, let the political branches not forget that it is also their sworn obligation, in the first and primary instance, to preserve and protect the Constitution in maintaining the federal balance. At the same time, the absence of structural mechanisms to require those officials to undertake this principled task argues against a complete renunciation of the judicial role: The federal balance is too essential a part of our constitutional structure and plays too vital a role in securing freedom for us to admit inability to intervene when one or the other · level of government has tipped the scales too far. The statute before us upsets the federal balance to a degree that renders it an unconstitutional assertion of the commerce power. Here neither the actors nor their conduct has a commercial character, and there is no commercial nexus to support the Act. In a sense, any conduct in this interdependent world of ours has an ultimate commercial origin or consequence. Should the commerce power be unlimited? When Congress attempts such an extension as is here evident, we must at least inquire whether the exercise of power seeks to intrude upon an area of traditional state concern . It is well established that education is a traditional concern of the States. There is a particularly important duty to make sure the federal-state balance is not destroyed in such an area. This allows states to remain the laboratories of experimentation, a role envisioned by the framers. Absent a stronger connection or identification with commercial concerns . iMi--·em, centF6I1 te tl"le 98 HIGH COURT CASE SUMMARIES to\ ~ ) l l11' ) United States v. Morrison (Government) v. (Accused Rapist) 529 U.S. 598, 120 S.Ct. 1740 (2000) THE SUPREMECOtJRT RESTRICTS APPLICATION OF THE AGGREGATION DO( TRINE TO REGULA­ TIONI OF ACTIVITIES THAT ARE ECONOMICINAND OF THEMSELVES • INSTANT FACTS An alleged rape victim sought to sue her accused attackers under the federal Violence Against Vomen Act (Act or VAWA). The accused! asse~s that VAWA is an unconstitutional exercise ~ congressional au­ thority. • BLACK LETTER RULE Congress may not, pursuant to the Commerc Clause, regulate a local activity solely on the asis that it has sub­ stantial effects on interst e commerce when viewed in its nationwide aggregate. • PROCEDURAL BASIS Appeal to the Supreme Court after the circuit court of appeals held that the VAWA is an unconstitutional exercise of the commerce power. • FACTS Brzonkala (P1) sued her fellow university student, Morrison (D) under the Violenc (Act or VAWA) , alleging that he assaulted and raped her. The VAWA is a feder federal civil remedy for victims of gender-motivated violence. Morrison (D) challen ty of the Act. The United States (Government) (P2) intervened to defend the Act's the Commerce Clause . Against Women Act I statute providing a es the constitutionali­ onstitutionality under • ISSUE May Congress regulate under the Commerce Clause local activities that are not ec nomic in nature? • DECISION AND RATIONALE (Rehnquist, C.J.) No. In the years- since NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. ( 937), Congress has had considerably greater latitude in regulating conduct and transactions under t e Commerce Clause than our previous case law permitted. Lopez [Gun-free School Zones Act declare to be an unconstitu­ tional exercise of the commerce power] emphasized, however, that Congress's gulatory authority is not without effective bounds. Of the three broad categories in which Congress ma properly exercise its commerce power, Brzonkala (P1) seeks to sustain the Act as a regulation of act vity that substantially affects interstate commerce. We agree that if the Act is to be sustained, thi is the category of activities-those substantially affecting interstate commerce-in which it must fit. Both Brzonkal1a (P1) and Justice Souter's dissent downplay the role that the economic nature the reg lated activity plays in our Commerce Clause analysis. But a fair reading of Lopez shows that the n neconomic, criminal nature of the conduct at issue was central to our decision in that case. A second important consideration in Lopez was that the statute contained no express jurisdictional lement which might limit its reach to a discrete set of firearms having an explicit connection with or effect on interstate commerce. Third, there were no express congressionall findings regarding the effects upon interstate HIGH COURT CASE SUMMARIES 101 United States v. Morrison (Continued) commerce of gun possession in a school zone. Finally, the purported link between gun possession and a substantial effect on interstate commerce was attenuated. Using these principles as reference points, the proper resolution of the present case is clear. Gender-motivated crimes of violence are not, in any sense of the phrase, economic activity. Thus far in our Nation's history our cases have upheld Commerce Clause regulation of intrastate activity only where that activity is economic in nature. Like the statute in Lopez, VAWA contains no jurisdictional element establishing that the federal cause of action is in pursuance of Congress's power to regulate interstate commerce. And while VAWA is supported by numerous findings regarding the serious impact that gender-motivated violence has on victims and their families, the existence of such findings is not sufficient, by itself, to sustain the constitutionality of Commerce Clause legislation . In both this case and Lopez, Congress's findings are substantially weakened by its reliance on a method of reasoning that we have already rejected as unworkable if we are to maintain the Constitution's enumeration of powers. If accepted, this reasoning would allow Congress to regulate any crime as long as the nationwide, aggregated impact of that crime has substantial effects on employment, production, transit, or consumption. The same concern we had in Lopez, that Congress might use the Commerce Clause to completely obliterate the Constitution's distinction between national and local authority, seems equally well founded here. We accordingly reject the argument that Congress may regulate noneconomic, violent criminal conduct based solely on that conduct's aggregate effect on interstate commerce . • CONCURRENCE (Thomas, J) The majority correctly applies our decision in Lopez and I join it in full. I write separately to point out that the very notion of a "substantial effects" test is inconsistent with the original understand­ ing of Congress's powers and with this Court's early Commerce Clause cases. By continuing to apply this rootless and malleable standard the Court has encouraged the view that the Commerce Clause has virtually no limits. Until we adopt a standard more consistent with the original understanding, Congress will continue appropriating state police powers under the guise of regulating commerce . • DISSENT (Souter, J) Our cases stand for the following propositions . That Congress has the power to legislate with regard to activity that, in the aggregate, has a substantial effect on interstate commerce. The fact of such a substantial effect is not an issue for the courts in the first instance, but for Congress, whose institutional capacity for gathering evidence and taking testimony far exceeds ours. The business of the courts is to review the congressional assessment simply for the rationality of concluding that a jurisdictional basis exists in fact. Applying these propositions here leads to only one conclusion. Unlike the statute at issue in Lopez, Congress assembled a mountain of data showing the effects of violence against women on interstate commerce. Congress explicitly state(j the predicate for the exercise of its commerce power. The sufficiency of this evidence as providing a rational basis for its findings cannot be seriously questioned. Indeed, gender-based violence in the 1990s was shown to operate in a manner sim'ilar to racial discrimination in the 1960s in reducing the mobility of employees and their production and consumption of goods shipped in interstate commerce. Like racial discrimination, gender-based discrimination bars its victims from ful l participation in the national economy. We rejected this formalistic economic/noneconomic distinction in Wickard. But again, history seems to repeating itself, for the theory of traditional state concern as grounding a limiting principle has been rejected previously . What the majority ultimately finds a way to ignore are the facts of integrated national commerce and' a political relationship between States and Nation much affected by their respective treasuries and constitutional modifications adopted by the people . The federalism of the past is no more adequate to account for those facts today than the theory of laissez-faire was able to govern the national economy 70 years ago. be Analysis: In Morrison, the Court strongly reaffirms its ruling and reasoning in Lopez. The significance of Lopez is the way it changed the standard applied to the federal regulation of intrastate activities. First, federal regulation of single state activities depends on whether such activities, when looked at as a class, substantially affect interstate commerce. Prior to Lopez , the Court had allowed such regulation.without 102 HIGH COURT CASE SUMMARIES CHAPTER TWO The Federal Legislative Power McCulloch v. Maryland Instant Facts: Maryland (P) attempted to impose a tax on the federal bank . The bank's cashier, McCulloch (0) refused to pay the tax. Maryland (P) sued McCulloch (0) , arguing that (1) the establishment of the bank is unconstitutional, and (2) the bank may be forced to pay state taxes. Black Letter Rule: Under the Necessary and Proper Clause, Congress may enact legislation so long as its ends are legitimate under the Constitution and the legislation is appropriate and plainly adapted to those ends. Gibbons v. Ogden Instant Facts: Ogden (0) was granted an exclusive ferry operations license by New York State. Gibbons (P) began a competing ferry service and challenges Ogden's (D) exclusive license under the Commerce Clause. Black Letter Rule: The federal commerce power extends to all commerce among and between the states and foreign nations, with only commerce having connections solely within a single state being unreachable under the commerce power. United States v. E. C. Knight Co. Instant Facts: A sugar refining company gained a monopoly in the industry by purchasing several other refineries . Black Letter Rule: Manufacturing is separate from " commerce" because it occurs before any goods are transported in interstate commerce, and thus the federal government may not regulate manufactur­ ing in and of itself. Carter v. Carter Coal Co. Instant Facts: Congress passed , pursuant to its commerce power, a law regulating the management­ employee relations in the coal mining industry. The law is being challenged on the ground that Congress does not have the power to regulate such activities because they do not constitute " interstate commerce." Black Letter Rule: Purely local activities, such as the negotiation of wages and working conditions, are outside of the Congress' realm of authority under the Commerce Clause. Houston, East & West Texas Railway Company v. United States [The Shreveport Rate Cases] Instant Facts: Oue to state regulations of intrastate transport, a railway company charged much higher rates for interstate transport between Shreveport, Lou'isiana and certain Texas locations than it did for transport exclusively within Texas, leading the Interstate Commerce Commission to implement price contmls. Black Letter Rule: Congress has authority to regulate lintrastate commerce where it has the potential to affect interstate commerce absent federal, regulation . AL.A. Schecter Poultry Corporation v. United States Instant Facts: Congress enacted a law governing wages, working conditions, and prices for poultry transported in interstate commerce. Wholesalers that purchase the chickens after they've arrived in­ state challenge the law as unconstitutional. H I G H CO U R T CAS E SUM MAR I E S 57 Black Letter Rule: Once goods that have traveled in interstate commerce are sold or disp?sed of in the state of their final destination, they are no longer in interstate commerce and thus not subJect to federal law. Hammer v. Dagenhart Instant Facts: A father wanting to put his two minor children to work in a cotton mill is suing on the ground that Congress' use of the commerce power to regulate child labor in the states by blocking the interstate transportation of child-made goods is unconstitutional. Black Letter Rule: The commerce power does not allow Congress to regulate in areas traditionally left up to the states' police power, such as the area of child labor laws. Champion v. Ames (The Lottery Case) Instant Facts: The Federal Lottery Act prohibited interstate shipment of lottery tickets. It is being challenged as unconstitutional in that such shipments are not commerce. Black Letter Rule: Congress may, pursuant to the Commerce Clause, prohibit the interstate shipment of items adjudged to be evil or pestilent in order to protect the commerce concerning all states. N.L.R.B. v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. Instant Facts: A steel corporation whose operations span the continent is being sued by the government for violating the National Labor Relations Act for committing unfair labor practices. Black Letter Rule: Congressional power to regulate interstate commerce extends to the regulation of intrastate activities that may burden or obstruct interstate commerce . United States v. Darby Instant Facts: A Georgia lumber company violated federal minimum wage/maximum hour laws. Its defense is that the federal government overreached its Commerce Clause authority in setting the standards. Black Letter Rule: Congress has the authority, under the Commerce Clause, to exclude any article from interstate commerce, in judgment that they are injurious to the public health, morals or welfare. Wickard v..F/lburn Instant Facts: Wickard (P) exceeded his allotted quota for wheat production, the excess amount to be used for his own consumption. He was fined by the government and seeks to have the quota ruled unconstitutional. Black Letter Rule: Congress' commerce authority extends to all activities having a substantial effect on interstates commerce, including those that do not have such a substantial effect individually, but do when judged by their national aggregate effects . Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States Instant Facts: An Atlanta, Georgia motel wishes to continue its racially discriminatory operations in spite of the 1964 Civil Ri'ghts Act (Act) barring racial' discrimination in public accommodations. Black Letter Rule: Congress has the power, under the Commerce Clause, to regulate local activities that could reasonably be seen as exerting a substantial and harmful effect upon interstate commerce. Katzenbach v. McClung, Sr. and McClung, Jr. Instant Facts: The owners of a restaurant in Birmingham, Alabama continued to exclude Negro patrons from their restaurant dining area, in violation of the Civn Rights Act of 1964. 58 HIGH COURT CASE SUMMARIES Black Letter Rule: Congress' commerce authority extends to any public commercial establishment selling goods that have moved in interstate commerce and/or serving interstate travelers. National League of Cities v. Usery Instant Facts: An amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act extended wage and hour requirements to state employees. The States are seeking to have the regulations as applied to them declared unconstitutional. Black Letter Rule: The Commerce Clause does not empower Congress to regulate states or local governments in their integral governmental functions. Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority Instant Facts: Application of the Fair Labor Standards Act to a city's mass transit system fuels a revisitation of National League of Cities v. Usery. Black Letter Rule: Congress has full authority under the Commerce Clause to regulate the traditional, or core, functions of state and local governments notwithstanding the Tenth Amendment. United States v. Lopez Instant Facts: A 12th-grade student was convicted of violating the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990, which makes it a federal offense to possess a gun near a school. Black Letter Rule: Congressional authority to regulate pursuant to the Commerce Clause extends to only those activities that rationally implicate (1) the channels of interstate commerce; (2) the instrumen­ talities of interstate commerce; or (3) activities having a substantial effect upon interstate commerce. United States v. Morrison Instant Facts: An alleged rape victim sought to sue her accused attackers under the federal Violence Against Women Act (Act or VAWA). The accused asserts that VAWA is an unconstitutional exercise of congressional authority. Black Letter Rule: Congress may not, pursuant to the Commerce Clause, regulate a local activity solely on the basis that it has SUbstantial effects on interstate commerce when viewed in its nationwide aggregate. Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Instant Facts: Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County (P) challenged federal authority over certain intrastate waters to be developed as a solid waste disposal site. Black Letter Rule: When statutory language is clear, a Commerce Clause analysis is unnecessary to determine the limitations <?n administrative authority. Pierce County, Washington v. Guillen Instant Facts: Guillen (P) sought through discovery to obtain information from Pierce County, Washington (D), concerning accidents occurring at the intersection where his wife died. Black Letter Rule: Under the Commerce Clause, Congress is empowered to regulate and protect the instrumentalities of interstate commerce, even though the threat may come only from intrastate commerce. New York v. United States Instant Facts: Congress passed legislation requIring states to either provide for radioactive waste disposal or take title to waste generated within their borders. The legislation is being challenged as an unconstitutional exercise of federal power over the States. HIGH COURT CASE SUMMARIES 59 ..=-== -' - -- . - - - - ",-,Oc",....~ Black Letter Rule: Congress does not have the authority to commandeer state governments by forcing them to implement particular regulations. Printz v. United States Instant Facts: The federal Brady Act required local law enforcement officials to temporarily administer its background check program. Two local law enforcement officers challenge the Brady Act's impress­ ment of local law enforcement officials. Black Letter Rule: Congress does not have authority to compel states to enact, enforce, or administer federal regulatory programs, and cannot circumvent this prohibition by conscripting state officials directly. Reno v. Condon Instant Facts~ Congress passed legislation placing certain prohibitions on the dissemination of private information given states by individuals in applying for a driver's license. One State challenges the constitutionality of the legislation as it applies to states. Black Letter Rule: States are required to comply with constitutionally valid legislation regulating state activities, even when compliance means incurring additional costs to be borne by the States. United States v. Butler Instant Facts: Congress attempted to regulate the quantity of local agricultural production through use of the taxing and spending powers. The regulation is challenged as being outside Congress's enumerated powers. Black Letter Rule: Congress may not use the taxing or spending powers to force compliance in an area where the Constitution does not give Congress independent power to regulate. Sabri v. United States Instant Facts: Sabri (D) challenged a federal anti-bribery statute as facially unconstitutional. Black Letter Rule: Under the Spending Clause, Congress is authorized to appropriate federal funds for the general welfare and use all rational means necessary and proper to further its spending power. South Dakota v. Dole Instant Facts: South Dakota (P) challenges a federal law withholding 5% of federal highway funds from any state with a drinking-age limit less than 21 years-of-age. Black Letter Rule: Valid use of the Spending power is subject to three requirements: (1) It must be used for the genera! welfare; (2) Any conditions on receipt of funds must be unambiguous; and (3) Any conditions must be related to the federal interest in the particular national projects or programs being funded. United States v. Morrison Instant Facts: An alleged rape victim sought to sue her accused attackers under the federal Violence Against Women Act (Act or VAWA) . The accused asserts that VAWA is an unconstitutional exercise of congressional authority. Black Letter Rule: Congress's authority to regulate under the Fourteenth Amendment extends only to state activity, not activities of private individuals. Katzenbach v. Morgan Instant Facts: New York voters are challenging a federal law prohibiting New York from enforcing its English literacy voting requirement. 60 HIGH COURT CASE SUMMARIES (jfll) tQt/l) Un1 ited States v. Morrison (Federal Government) v. (Assault VicUm) 529 U.S. 598, 120 S.Ct. 1740 (2000) CONGRESS MAY NOT REGULATE PRIVATE INDIVIDUALS PURSUANT TO THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT • INSTANT FACTS An alleged rape victim sought to sue her accused attackers under the federal Violence Against Women Act (Act or VAWA). The accused asserts that VAWA is an unconstitutional exercise of congressional au­ thority . • BLACK LETTER RULE Congress's authority to regulate under the Fourteenth Amendment extends only to state activity, not activities of private individuals. • PROCEDURAL BASIS Appeal to the Supreme Court after the circuit court of appeals held that the VAWA is an unconstitutional exercise of the commerce power. • FACTS Brzonkala (P1) sued her fellow university student, Morrison (D) under the Violence Against Women Act (Act or VAWA), alleging that he assaulted and raped her. The VAWA is a federal statute providing a federal civil remedy for victims of gender-motivated violence. Morrison (D) challenges the constitutionali­ ty of the Act. The United States (Government)(P2) intervened to defend the Act's constitutionality under the Commerce Clause and the Fourteenth Amendment. • ISSUE Does the Fourteenth Amendment provide Congress the authority to regulate the activities of private individuals? • DECISION AND RATIONALE (Rehnquist, C.J.) No. The Government (P2) argues that VAWA is a constitutional exercise of Congress's remedial power under § 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment, which it expressly invoked as a source of authority to enact VAWA. The Government's (P2) argument is founded on an assertion that there is a pervasive bias in various state justice systems against victims of gender-motivated violence. A voluminous congressional record supports this assertion. Fourteenth Amendment analysis is well settled. The Amendment's language and purpose set certain limitations on the ways in which Congress may attack discrimination. These limitations are necessary to prevent upsetting the framer's carefully crafted balance of power between the States and the National Government. Foremost among these is the time-honored principle that the Fourteenth Amendment, by its very terms, prohibits only state action. It erects no shield against merely private conduct, however discriminatory or wrongful. This is the rule from United States v. Harris and the Civil Rights Cases, decided shortly after the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted. The Government's reliance on United States v. Guest as contrary authority is misplaced. In Guest the Court had no occasion to consider . whether the Fourteenth Amendment authorizes legislation applicable to private individuals because "the indictment [charging private individuals with conspiring to deprive blacks of equal access to state facilities] in fact contain[ed) an express allegation HIGH COURT CASE SUMMARIES 125 United States v. Morrison (Continued) of state involvement." The opinions of three Justices in Guest that Congress does have Fourteenth Amendment authority to regulate private individuals does not, therefore , have any force of law. The Act is not aimed at any state or state actor, but at individuals who have committed criminal acts motivated by gender bias. The Act is, therefore, unlike any of the § 5 remedies that we have previously upheld. Accordingly, we hold that the VAWA cannot be sustained under the Fourteenth Amendment. • DISSENT (Breyer, J.) I write to express my doubts as to the Court's reasoning in rejecting the Fourteenth Amendment as a proper source of authority for enacting VAWA. The Court is correct in asserting that the Fourteenth Amendment does not authorize Congress to remedy the conduct of private persons. The . Government's (P2) argument, however, is that Congress used § 5 to remedy the actions of state actors, namely, those States which, through discriminatory design or the discriminatory conduct of their officials, failed to provide adequate state remedies for gender-motivated violence. Though the private actors here in question did not violate the Constitution, this Court has held that Congress at least sometimes can enact remedial legislation prohibiting conduct that is not, itself, unconstitutional. Such action intrudes little upon either States or private parties. Given the relation between remedy and violation-the creation of a federal remedy to substitute for constitutionally inadequate state remedies­ where is the lack of "congruence"? Analysis: The majority is correct in asserting that VAWA is distinguishable from all other legislation upheld under the Fourteenth Amendment. It is not aimed at state action and does not fit with anyone of the proxies for state action the Court has allowed, such as cases holding private actions to have a "public function," thus allowing regulation , or the " nexus" cases, where state and private action are somehow linked. Another exception carved out by the Court is, arguably, more applicable. This is the government­ encouraged/authorized private discrimination exception. The possible, though weak, argument is that by continually failing to adequately enforce state laws against gender motivated violence, the State is indirectly/implicitly encouraging or authorizing such criminal conduct. Such an argument suggests that states have a duty to enact and fully enforce criminal statutes, with a failure to do so being a breach of the duty, thus satisfying the Fourteenth Amendment's state action requirement. 126 HIGH COURT CASE SUMMARIES (CI\Ir) (rD South Dakota v. Dole. (State) v. (Secretary of Transportation) 483 U.S . 203, 107 S.Ct. 2793 (1987) SUPREME COURT ALLOWS CONGRESS LIBERAL USE OF THE SPENDING POWER • INSTANT FACTS South Dakota (P) challenges a federal law withholding 5% of federal highway funds from any state with a drinking-age limit less than 21 years-of-age . • BLACK LETTER RULE Valid use of the Spending power is subject to three require­ ments: (1) It must be used for the general wel­ fare; (~~) Any conditions on receipt of funds must be unambiguous; and (3) Any conditions must be related to the federal interest in the particular national projects or programs being funded . • FACTS Congress passed legislation (§ 158) directing Dole (D), the Secretary of the Treasury, to withhold 5% of federal highway funds from any state that fails to set its legal age for alcohol consumption at 21 years. South Dakota (P) asserts that § 158 violates the constitutional limitations on congressional exercise of the spending power, as well as the Twenty-first Amendment to the Constitution . • ISSUE May Congress use its spending power to regulate activities in areas reserved to the States? • DECISION AND RATIONALE (Rehnquist, C.J.) Yes. Incident to the spending power, Congress may achieve its broad policy objectives by conditioning the receipt of federal funds upon compliance by the recipient with federal statutory and administrative directives. Such use of the spending power is, of course, not unlimited, but is subject to several general restrictions. The first limitation is that the exercise of the spending power must be in pursuit of the ",general welfare." In conSidering whether this requirement is met, courts should defer substantially to the judgment of Congress . Second, any conditions must be set forth unambiguously, allowing the States to exercise their choice knowingly, cognizant of the consequences of their participation. Third, conditions on federal grants must be related to the federal interest in particular nationwide projects or programs. Here, the provision is unmistakably for the general welfare. The condition is also unambiguous, indeed, coulld not be more clearly stated. Third, the condition imposed is directly related to one of the main purposes for which highway funds are expended~safe interstate travel. We have also held that a perceived Tenth Amendment limitation on congressional regulations of state affairs did not, at the same time, limit the range of conditions legitimately placed on federal grants. Although we have also recognized that in some circumstances the financial inducement might be so coercive as to pass the point at which pressure turns into compulsion. This is not, however, the case here as only a relatively small percentage of highway funds are at stake. South Dakota's (P) contention that the success of the progJam proves its coercive nature is without merit. A conditional HIGH COURT CASE SUMMARIES 123 I .p----------------­ South Dakota v. Dole (Continued) grant of money is not unconstitutional simply by the reason of its success in achieving the congression­ al objective . • DISSENT (Brennan, J) I agree with Justice O'Connor that a minimum drinking age law falls squarely within the ambit of those powers reserved to the States by the Twenty-first Amendment. Congress cannot condition receipt of funds in a manner that abridges this right. • DISSENT (O'Connor, J.) I cannot agree that § 158 is a condition on spending reasonably related to the expenditure of federal funds. Rather, it is an attempt to regulate the sale of liquor, an attempt that lies outside Congress's power to regulate commerce because it falls within the ambit of § 2 of the Twenty­ first Amendment, which reserves such regulation to the States. We have repeatedly said that Congress may condition grants under the spending power only in ways reasonably related to the purpose of the federal program. In my view, establishment of a national minimum drinking age is not sufficiently retated to interstate highway construction to justify so conditioning funds appropriated for that purpose. Analysis: Justice O'Connor disagrees with the majority in this case. Justice O'Connor would require there to be a direct nexus between the funds' purpose and the conditions of their use, while the majority would require only a tangential relationship. Furthermore, the majority seems to be willing to let Congress be the "judge" of whether there exists the required reasonable relationship between the funds' purpose and the conditions. On another note, both Justices O'Connor and Brennan interpret the Twenty-first Amendment as reserving the regulation of alcohol exclusively to the States. Under this interpretation, Congress is absolutely foreclosed from exercising influence, in any way, on state regulation of the alcohol age limit. . 124 HIGH COURT CASE SUMMARIES