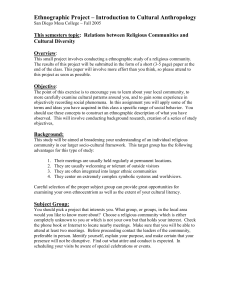

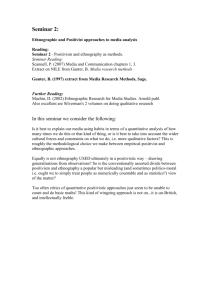

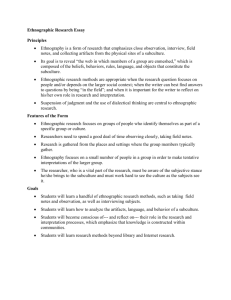

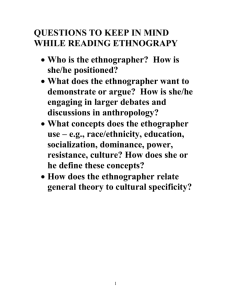

Basic Classical Ethnographic Research Methods

advertisement