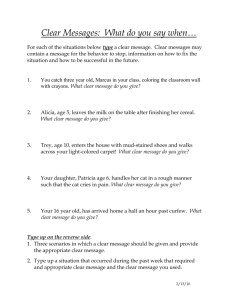

“LIVING DEAD” Sermon preached by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Hostetter

advertisement

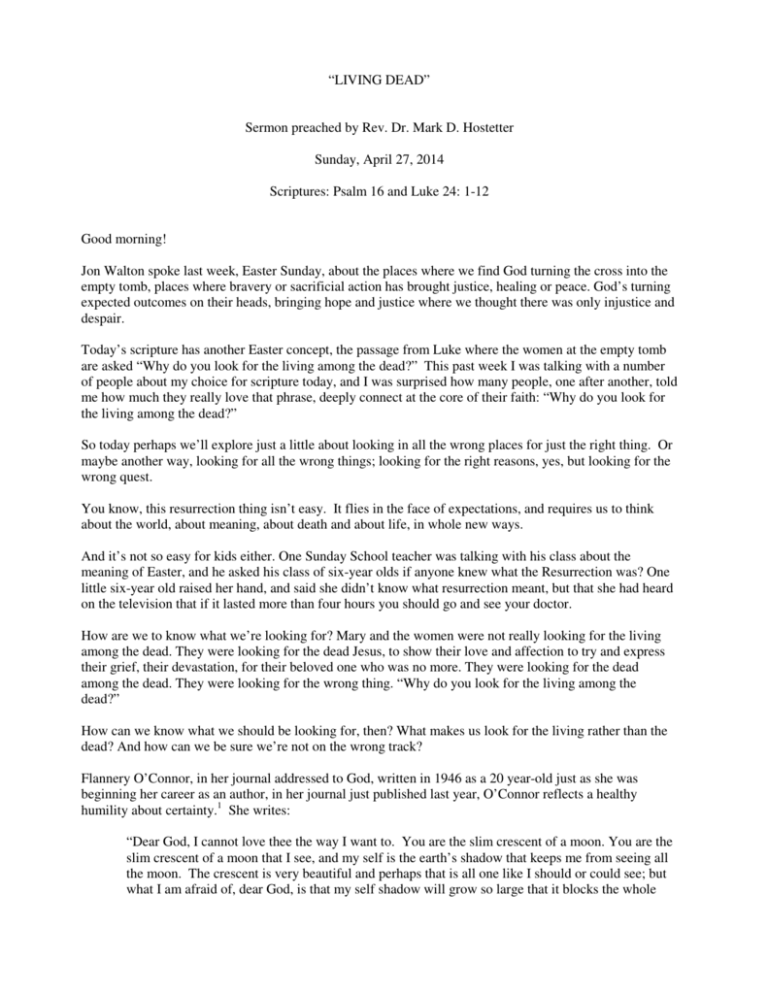

“LIVING DEAD” Sermon preached by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Hostetter Sunday, April 27, 2014 Scriptures: Psalm 16 and Luke 24: 1-12 Good morning! Jon Walton spoke last week, Easter Sunday, about the places where we find God turning the cross into the empty tomb, places where bravery or sacrificial action has brought justice, healing or peace. God’s turning expected outcomes on their heads, bringing hope and justice where we thought there was only injustice and despair. Today’s scripture has another Easter concept, the passage from Luke where the women at the empty tomb are asked “Why do you look for the living among the dead?” This past week I was talking with a number of people about my choice for scripture today, and I was surprised how many people, one after another, told me how much they really love that phrase, deeply connect at the core of their faith: “Why do you look for the living among the dead?” So today perhaps we’ll explore just a little about looking in all the wrong places for just the right thing. Or maybe another way, looking for all the wrong things; looking for the right reasons, yes, but looking for the wrong quest. You know, this resurrection thing isn’t easy. It flies in the face of expectations, and requires us to think about the world, about meaning, about death and about life, in whole new ways. And it’s not so easy for kids either. One Sunday School teacher was talking with his class about the meaning of Easter, and he asked his class of six-year olds if anyone knew what the Resurrection was? One little six-year old raised her hand, and said she didn’t know what resurrection meant, but that she had heard on the television that if it lasted more than four hours you should go and see your doctor. How are we to know what we’re looking for? Mary and the women were not really looking for the living among the dead. They were looking for the dead Jesus, to show their love and affection to try and express their grief, their devastation, for their beloved one who was no more. They were looking for the dead among the dead. They were looking for the wrong thing. “Why do you look for the living among the dead?” How can we know what we should be looking for, then? What makes us look for the living rather than the dead? And how can we be sure we’re not on the wrong track? Flannery O’Connor, in her journal addressed to God, written in 1946 as a 20 year-old just as she was beginning her career as an author, in her journal just published last year, O’Connor reflects a healthy humility about certainty.1 She writes: “Dear God, I cannot love thee the way I want to. You are the slim crescent of a moon. You are the slim crescent of a moon that I see, and my self is the earth’s shadow that keeps me from seeing all the moon. The crescent is very beautiful and perhaps that is all one like I should or could see; but what I am afraid of, dear God, is that my self shadow will grow so large that it blocks the whole 2 moon, and that I will judge myself by the shadow that is nothing. I do not know you, God, because I am in the way. Please help me to push myself aside.” That humbleness O’Connor expresses with such beauty has to be at the core of our search, our quest for what we should be looking for. It’s going to be something unexpected, something new, something different. And if we think, once and for all, we have it figured out completely, well . . . you can be sure you’re on the wrong track and will be searching for something that’s no longer relevant, that’s effectively dead. We all mourn at the polarization in our church, with everyone feeling so strongly that they are right, indignant to the point of congregations leaving the denomination, or others who would force an orthodoxy, even a progressive one, on every member’s conscience. Mary’s reply to the two angels about why she is crying at the tomb sums it up for one preacher. Remember in John, Mary answers, “They have taken away my Lord and I do not know where they have laid him.” Our people in our denomination are crying because faithful believers on either side of the aisle feel like those on the other side have “stolen their Jesus” and they “do not know where they have put him.” As a presbytery executive said to one preacher when he was a candidate for ministry, still in seminary, “If you can’t entertain the idea that, on any given theological issue, you may be wrong, you may want to reconsider getting ordained.”2 That openness to new ways of thinking, to new ways of living, is critical if we care to see the fullness of God’s grace. British science fiction writer John Wyndham has a great quote about life’s meaning: “The essential quality of life is living; the essential quality of living is change; change is evolution; and we are a part of it. The static, the unchanging, the enemy of change, is the enemy of life.” 3 How do we then look for the living, for life and transcendence and meaning, amidst all the dead around us? Faithful often get trapped looking for the living among the dead, mistakenly thinking holy what is mortal, holding tight to what is long past its expiration date, making a god of something other than God alone. Dead words: language we have used so repeatedly, whose meaning is so nailed down and rigid, they have lost all power, trapped, unable to breathe. Dead tradition: going through the motions, of liturgy, of custom, of doing things the way we’ve always done them. Using tradition as a means of exclusion. Dead categorizations: perpetuating stereotypes and prejudices, forcing people into predetermined boxes, seeing the world in black and white, a zero-sum game of “us” versus “them.” Dead facts: refusing to keep an open mind to new information, new approaches, new visions, in an everchanging world and an ever-changing church. Dead priorities: holding tight to our privileges, focusing on what we own rather than who we are, thinking that God favors our side over others. Our Jesus is fiercely, wildly, unpredictably alive. He can’t be pinned down into conventional categories. He challenges the traditions of his society. And ours. He puts a new spin on standard interpretations. He overturns structures that no longer meet their original purpose. Even rules of the physical world aren’t fixed forever. Water doesn’t stay water for Jesus. Dead people don’t stay dead. Nothing can restrain the creative power of God. 3 Are we looking for the right thing? Do we prefer our God dead rather than living? After all, a dead God never makes demands on our life, never challenges us, never gets in the way of what we want to do. A living God might mean we’d have to change our priorities, challenge our choices, change our minds, love our enemies. But a dead God can’t heal our heart, can’t lift our spirit, can’t fill us with overwhelming joy, can’t hear our prayers. A dead God can’t speak to our soul. Parents of teens and tweens and pre-tweens will be able to relate to the fact that my kids have now seen the Disney movie “Frozen” no fewer than seven times (and once dubbed in French). I’m not proud of it, but there it is. The film’s lesson, at its highest level, through all the fantasy and the magic and the orchestrated crescendos and ballads, is pretty simple: Don’t let your life be dominated by fear. And know that selfless love is what saves us in the end. Who knew those Disney dreamers and we First Pres churchgoers had so much in common! I suppose, too, part of helping to keep us on track, looking for the living among the living, is having a healthy concept of how we should go about looking. I was having a great conversation with a professor of leadership development over an after-ski beverage out in Colorado just this past spring break. Now it may have been the effects of that warming beverage, or maybe the 9,000 foot altitude in the mountains, but his formulation sounded pretty good. To be effective, he said, a leader needed four things. A leader needed a true sense of calling, of vocation, a conviction that you were in the place where you were supposed to be. A leader needed a connection with something greater, call it a holy presence, or a sense of awe. A leader needed authenticity, connection with others, trust born from a belief that we are truthful and genuine. And a leader needed passion, wholeheartedness, the commitment and presence that demonstrates we are unhesitatingly “all-in.” Not bad for a slope-side conversation – mantras that couldn’t hurt in helping us focus on value and meaning. Yet even if we gain some clarity, however dimly seen, about just which living God we are seeking, we are following, our fear of death can sometimes keep us on the wrong quest. Which of course brings to mind another story. While on a beach vacation in the warmth of the sun, getting away from it all, a wealthy and very proper English businessman received a telegram message from his butler back in England. (Now you know this was some years ago, since I’m not sure even Western Union still delivers telegrams anymore.) In any case, the telegram from the butler read simply, two words: "Cat dead." Devastated and distraught at the loss of his beloved pet, the businessman cut short his holiday and returned home. After giving the cat a decent burial in the garden, he talked with his butler about the cold-hearted nature of the telegram. "You should break bad news gently," he said. “If I had been telling you that your cat had died, I would have sent a telegram saying: "The cat's on the roof and can't get down." Then a few hours later after that first telegram that said "The cat's on the roof and can't get down," I would have sent another telegram, saying: "The cat's fallen off the roof and is badly hurt." Finally, a couple of hours after that, I would have sent a third telegram, saying: "The cat had sadly passed away." That way, you would have been gradually prepared for the bad news and would have been able to deal with it better." "I understand, sir," said the butler. "I will bear that in mind in future." With that, the businessman booked 4 another ticket to his island getaway and resumed his holiday. Two days later, he received another telegram from his butler. It read: "Your mother's on the roof and can't get down." Brian Blount, a good friend and President of Union Seminary in Richmond, has a new book just out this year, called “Invasion of the Dead.4 What a great title for a book on the resurrection! Like exasperated parents on a long, arduous, winding road trip, trapped in a steamy, sweaty car, jammed with luggage, snacks, and physically pent-up and emotionally stirred-up children – we all know too well that particular episode – we divert attention and questions about the destination, lest the fervor over being there wrecks the process of getting there. Stop talking about it. Stop obsessing over it. No, we are not there yet. We’ll get there when we get there. And as Christians, we focus on Good Friday, we put our emotions into Good Friday. After all, we are people of the cross. It identifies us, it marks us. The cross is our brand, our logo, our not-so-secret symbol, if you will. Blount goes on to say, that maybe it’s not in the killing fields of Golgotha where we should tarry, not on the crucifixion and death of Jesus. But rather, it’s the graveyard; that is the place you want to be. If something crazy does not happen in the graveyard, the meaning of what happened on the cross is diminished. Rather, maybe as Easter people, we Christians should instead use life to reveal the meaning of life. In popular American culture, it’s certainly an ever-present reality to use death to reveal the meaning of life. The more spectacular the death the better. The more gruesome the dying is, the more clarified our appreciation of life becomes. The vampires drain life from the living; the explosives destroy everything in their wake; the floods and volcanoes and tidal waves and earthquakes and asteroids bring death on a cosmic scale. When the book or movie is ended, our view of life is then renewed with a grander sense of appreciation for life, for what we take for granted. But rather than looking through that usual prism of death, and hoping through all the confusion and clutter we can somehow find the meaning of life, instead maybe we start with a clear vision of life, embrace the joy and love in creation’s grace, marvel at how life obliterated death, and in that process of making death meaningless, reveal life’s essence and purpose. We begin, and end, with resurrection. It’s the “Dawn of the Dead,” Blount’s “Invasion of the Dead,” not because of death, but because life – and all the joy of life – is the only truth. To win, God must detonate a force as ferocious for life as God’s enemies are vicious for death. And that ferocity, that tenacity, that inevitability for life, it is unquestionably true. I love reading science articles. I look forward, with the joy of an 11-year-old, to the arrival of the Science Times section on Tuesdays, to the monthly National Geographic in my mailbox, anything my nerdy-geek within can get my hands on. So as your scientist-preacher in the pulpit this Sunday, at least to me it’s clear. The force of life permeates everything on earth. From the highest mountain to the deepest abyss; from the hottest place on earth to the cold of near absolute-zero, life is what prevails, always. We tend to focus on death, what it takes to kill something, to kill us, but the fact is that it seems no matter what the circumstance, no matter the tragedy, on an individual or an evolutionary scale, from microbes and resistant bacteria, to jellyfish and cockroaches, dinosaurs to DNA, it is life – the dynamic force of living things, of life, that always prevails, to repopulate, to create a new and different world, a force that never ceases. Life prevails despite humankind’s seeming unceasing efforts to destroy it. 5 It’s not death that is the only constant; it’s life. You may have come here last Easter Sunday, you may have come here today, bearing the burden of death, like Mary and the women bearing the burden of death who came to the tomb. You don’t have to go home the same way. Why do you seek the living among the dead? Our hearts are not captive to death any longer. We don’t have to surrender our lives to fear and despair. The joy that endures is the life we know we have been given. The life we live is not ours. It is God living in us, the life that will last far beyond our earthly adventures. Our focus, the focus of existence, God’s focus, is not on death. Our source of meaning begins, and it ends, with life. Or maybe more accurately, it begins with life, and it never ends. So to leave you with a smile, a quick story of St Peter at the gates of heaven. Three people, a doctor, and a nurse, and an HMO executive, are at the pearly gates. St. Peter soon appears to speak with them, and asks them what good they have done in their lives. The doctor goes first: “I have devoted my life to the sick and needy and have had a part in caring for and healing thousands of people.” Peter thinks that's great, and tells the doctor to go ahead and enter into heaven. The nurse goes next: “I have supported patients in suffering and in health for my entire working life.” Peter says “Wonderful – please proceed in with the doctor.” “And what about you?” St. Peter asks the third person, the HMO executive. The HMO executive, feeling confident, tells St Peter, “I was the president of a very large Health Maintenance Organization and was responsible for the healthcare of millions of people all over the country.” St. Peter pauses for only a moment, then says, “Oh, I see. Please go on in . . . but you can only stay 2 nights!” So on this Sunday after Easter, join with me, all together, in our loudest outside voices, proclaiming our truth, as we seek the living among the living. Christ is risen! He is risen, indeed! Shout it from the rafters, so our ancient sanctuary walls ring. Christ is risen! He is risen, indeed! AMEN. © Copyright 2014, Mark D. Hostetter 1 Flannery O’Connor, A Prayer Journal, Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2013. David Lee Jones, “Managing Ecclesial Polarization,” Presbyterian Outlook, April 28, 2014. 3 John Wyndham, The Chrysalids (US title: Re-Birth), Joseph/Ballentine 1955. 4 Brian K. Blount, Invasion of the Dead: Preaching Resurrection, Westminster John Knox 2014. 2