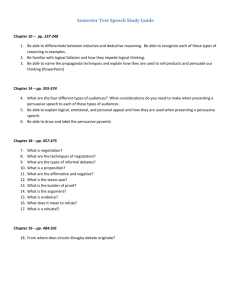

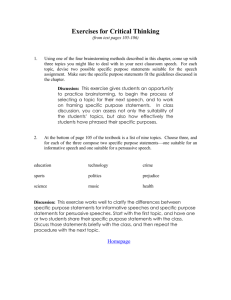

persuasive speaking - The Public Speaking Project

advertisement