THE OFFENDER'S RESPONSE TO REJECTED FORGIVENESS

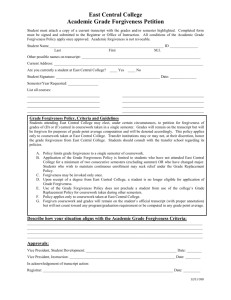

advertisement