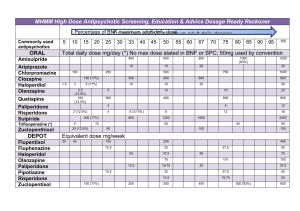

Chapter 9: Antipsychotic Drugs

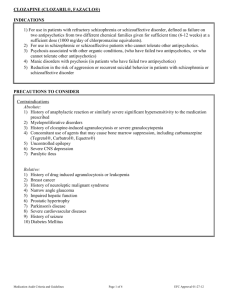

advertisement