Social functions of location in mobile telephony

advertisement

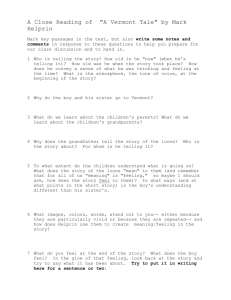

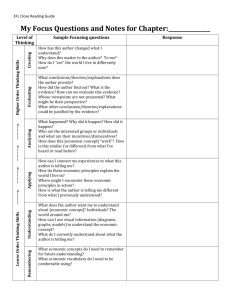

Pers Ubiquit Comput (2006) 10: 319–323 DOI 10.1007/s00779-005-0052-5 O R I GI N A L A R T IC L E Ilkka Arminen Social functions of location in mobile telephony Received: 26 May 2004 / Accepted: 8 March 2005 / Published online: 10 November 2005 Ó Springer-Verlag London Limited 2005 Abstract Location appears to be one of the most important aspects of context in mobile communication. It is a complex piece of information involving several levels of detail. Location intertwines with other relevant aspects of context: the parties’ present activity, relative time and identities. The analysis of mobile conversations provides insights into the functions of ‘‘location’’ for mobile users. Most mobile calls involve a sequence in which location is reported. Location is made relevant by the parties’ activities. Location telling takes place in five different activity contexts during mobile calls. Location may be an index of interactional availability, a precursor for mutual activity, part of an ongoing activity, or it may bear emergent relevance for the activity or be presented as a social fact. Typically, joint activities make relevant spatio-temporal location such as distance in minutes from the meeting point via the vehicle used. For users, location does not appear to be relevant in purely geographical terms. Keywords Location awareness Æ Location-aware computing Æ Context awareness Æ Context-aware computing Æ Conversation analysis Æ Mobile conversations studies have largely neglected a more detailed scrutiny of how mobile individuals orient to their location in the wild. Mobile phone users rank location as the second most important aspect of context [6]. Location, however, is a complex piece of information because participants refer to location on several levels of detail (city, locality, building, position in the building or room, etc.). Further complexity comes from the fact that location intertwines with other relevant aspects of context: the identity of the persons, relative time of the parties and the present activity of both communicators [6]. Consequently, location and context are both dynamic; i.e. the relevance of location for the actor depends on the other aspects of the context [7, 8]. As an aspect of context changes, the value of location also changes. To understand the dynamic nature of location, we have to study the actual communicative practices in which location gains its value. These kinds of naturalistic user studies bear also design implications as they enable the researcher to pinpoint the users’ requirements exactly at the moment when they emerge. In this article, the systematics of mobile communicators’ orientation to their location is mapped and the potential design implications are considered. 1 Introduction 2 Location-aware mobile telephony Location-aware systems may enhance mobile computing [1]. Location appears to be one of the most important aspects of context in mobile communication [2, 3]. Indeed, mobile telephones are pervasively used for coordination of an ongoing distant social activity [4, 5]. People use mobiles to communicate where they are, when they come and to arrange meetings. However, I. Arminen Department of Sociology and Social Psychology, University of Tampere, 33014 Tampere, Finland E-mail: Ilkka.arminen@uta.fi Tel.: +358-3-2156563 Fax: 358-3-2156080 Location-aware mobile services utilize the information about the location of the user to offer or to adapt the service accordingly. Location awareness can mean either utilizing the position of the device itself or tracking the location of the user. User studies show that there are high expectations concerning location-based services (LBSs) [9]. The users’ needs for LBSs are bound to time and situation and involve individual variation [10]. Temporal, situational and inter-individual variations in the needs for LBSs require further analysis so that LBS would meet the user requirements. Jordan et al. [11] suggested that the notion 320 of affordances would help to link geographic information to the users’ actual needs by modelling task-scaled definitions of locations. Recently, there have been some studies of mobile conversations conducted by analysing their recordings [12, 13]. Weilenmann has studied particularly the ways in which location references are used to signal communication difficulties: ‘‘I can’t talk now, I’m in a fitting room’’. In these cases, location references were embedded in a description of activity that limited or made participation impossible. The activity in which the person was engaged was the feature that scaled the information value of location. Laurier, for his part, has shown how mobile professionals routinely stated their locations on a mobile phone as a part of their mobile usage. Both these studies on actual communicative practices point out how the value of location is embedded in the activity in which the mobile user is engaged. In this article, I will elaborate and detail the way in which location features in mobile users’ actual communicative behaviour. 3 The case study and research method To analyse actual mobile telephony, a set of 74 Finnish mobile phone conversations were recorded in summer 2002. The mobile phone used by the study subject was the recording device. The mobile calls of four individuals (two women and two men aged 23–38 years) were taped within about a week with the permission of all communicative parties. The participants could choose which calls were recorded, and their anonymity was guaranteed. The material covered both mobile-to-mobile and landline-to-mobile or mobile-to-landline conversations. Most of the calls were made to friends and relatives, but some were work related. The calls were transcribed and analysed in detail by using conversation analytical (CA) methods [14, 15]. The transcripts are not included in this article; however, the conclusions drawn on the basis of the material will be presented (for transcribed data, contact the author, or check his other publications [16]). The aim of the study is to understand communicative behaviour in mobile contexts. CA methodology was used to open up the realtime co-ordination of social action that was achieved by means of mobile technologies. The final objective is to elaborate the new social practices that new technologies allow. These new practices are open for further augmentation with new applications. their location in most calls anyway. In my data, 62 mobile calls out of 74 involved a sequence in which the mobile party stated her or his location to the other party. Location telling is an extremely common, even a predominant, practice in mobile calls. Location telling during mobile calls takes place in five different activity contexts. In other words, location seems relevant for the parties in mobile interaction during five different types of activities. Location may be an index of interactional availability, a precursor for mutual activity, part of an ongoing activity, or it may bear emergent relevance for the activity or be presented as a social fact (see Fig. 1). Naturally, the data set is too small for definitive statistical generalizations, but the activity types are strongly recurring and their distribution could be studied more reliably with a larger quantifiable sample. The earlier studies, on landline calls, have shown that in the opening the answerers orient to demonstrating their interactional availability or the possible problems before the reason for calling is dealt with [17, 18]. In mobile calls, the answerers may volunteer to state their infelicitous position for interaction through stating their location, such as being in the toilet (here and elsewhere, the details come from my set of calls, unless otherwise stated) or being in the fitting room [13]. This may lead into a trajectory for rearranging a new call after some time or for dealing with the problematic situation in another way. Likewise, audible ‘‘untypical’’ voices (the answerer’s heavy breathing) or background noise (a noisy restaurant or disco) or remarkable delays in answering may prompt the caller to make a ‘‘where-areyou’’ inquiry. Occasionally, callers may anticipate problems in the answerer’s availability (e.g. in the beginning of early-morning or late-night calls), and inquire about the answerer’s availability or whereabouts. These kinds of inquiries and location-telling sequences are made as a preliminary to the call proper, before the parties have engaged in whatever their reason for getting in touch is. Interestingly, these ‘‘interactional availability’’ location queries or telling are in fact not as Social fact (no activity implication) (n=4) 6% Interactional Emergent relevance availability (n=10) for activity (n=6) 15 % 9% Part of the ongoing activity (n=14) 22 % 4 Activity contexts for location telling Mobile communication devices are by definition location free; they can be used anywhere anytime. The usage of mobile communication device does not technically require the parties to get to know where the other party is [5]. Interestingly, the parties seem to communicate Precursor for activity (n=31) 48 % Fig. 1 Types of location telling in mobile phone calls (N=74) 321 common as one might have expected on the basis of the stereotypical images of mobile talk. It is possible that a mobile phone etiquette has already developed. Namely, the interactional availability inquiries presume that a call is answered anyhow, not only when the answerer is available for a conversation, and that may have been the case when people were not used to using mobile phones. Currently, many people (at least in this data set) may have learned to use the silent mode of the phone and to answer calls only when it suits them. Infelicitous answering and the parties’ concern about that seem relatively rare. However, the data were collected at one point in time and therefore the guesses about the development of the mobile phone etiquette are hypothetical. Most location-telling sequences in these data are linked with practical arrangements. People state their location as a precursor for some practical arrangement, like a meeting, seeing in some place, or finding out about their schedules that somehow impinge on their mutual task. Location telling may be an answer to a ‘‘pre-sequence’’ [19] such as ‘‘what are you doing?’’. Typically, location is asked when the parties seek to find out about possibilities for mutual activity such as dinner, etc. These practical aspects of location will be discussed in more detail later. Location telling is also commonly done as a part of the real-time ongoing activity in which the parties are engaged. A car driver may call and ask which direction to take; notably this is a fast real-time co-ordination task, and details of the talk also show the parties’ orientation to a fast exchange of information. Location can also be a mutual real-time co-ordination task, such as seeing each other in the cafeteria to meet there. Emergencies and hazardous situations are salient class of realtime location-sensitive activities; a car driver may, for instance, warn the car behind about a deer by the road. Finally, a kind of location that is also realized during the ongoing activities is a virtual location referring to a web page or other material at hand to be shared with the communicative partner. A not common, but existing, social practice involves location telling due to its social, symbolic qualities (in contrast to being a part of practical arrangements). In a call, the caller says that she is on the beach. Her location telling is not done in the context of asking the answerer to join the caller on the beach. But mentioning ‘‘beach’’ seems to have been done because of its connotative meanings that signify ‘‘having fun’’. In that way, location telling is used for arousing symbolic meanings, which for their part have practical bearings. Here the caller says she is on the beach to lure or seduce the other party to join her later to have a fun evening. This kind of usage of location telling is not a very common practice, but it is intrinsically an interesting social activity. Some calls also involve informing of one’s own location to the other party without any explicit activity implications. In a call, the called person says that she is in her home region (far away from the town in which she studies), while she answers to a ‘‘how-are-you’’ question. Here, location telling may have a negative implication; the other party is not available to any mutual activity because she is away from the town. However, the location is not mentioned in connection with practical arrangements; its practical implications are not dealt with in any observable way either. It is nevertheless noticeable that informing like this is not a common practice. Sometimes location may have some symbolic significance, and those properties may be discussed. The relevance may be biographical, such as a place of personal importance; it may also be cultural, such as a historic or aesthetic significance. Perhaps surprisingly, among ordinary calls, the socio-emotional, symbolic significance of location does not seem to be common. Finally, there are also a number of calls that do not involve any location telling (12 out of 74). Nevertheless, a large majority of calls involve location telling. Mostly location telling is related to prospective or ongoing social activities in which the parties are involved. Location may also have a direct interactional significance that is brought up if a party’s availability for interaction is limited due to some situated activity. Also, the symbolic qualities of location may be brought up, occasionally bearing the practical significance as well. The different layers of meaning of location can also be embedded and realized during the same interaction. 5 Social functions of location for mobile telephony Overall, location seems to have at least three distinct social functions in mobile calls. Parties may address the interactional location; i.e. whether or not the answerer is available for interaction at that moment. Sequentially, interactional location is (potentially) relevant at the very beginning of the call, before the reason for calling is dealt with. As elsewhere, also in this data set, many, even most, of the mobile calls are made as a part of practical arrangements. The practical arrangements make relevant the praxiological location that describes the parties’ availability for action. The manner in which location is made relevant and described to the other party is activity-bound, i.e. the relevance of location depends on the nature of activity, for instance, and the very same location is different for a walker and a car driver. Lastly, location can also have a socio-emotional content. This socio-emotional content may also have a practical value for the parties. Discussion and findings of this study are summarized in Table 1.It is mainly based on my own data but it also summarizes the existing knowledge of the field. The interactional, proximal location is dealt with at the very beginning of the call. The caller may ask if the called can talk/communicate. Occasionally, the called may inform the caller about problems in communicational availability. At least in this data set, but most likely also more generally [5, 12], the mobile phone is the device for 322 Table 1 Social functions of location for mobile communication Location Function of Location I International availability – audio-physical and social features of proximal location: noise (disco), network availability, (train, remote areas), involvement with proximal interaction, intimacy of situation (toilet, etc.) – spatio-temporal availability: readiness to engage in action (Are you doing anything special? Can you come to x?) – spatio-temporal location of a party vis-à-vis the engaged activity: temporal distance (half an hour [by car, by train, on foot, etc.] – real-time perspicuous location in an ongoing action: visibility (I’m at x where are you), real-time location (I just saw a reindeer by the road, beware—[told to the car driving behind]) – instructable location: spatialized requests (I’m/accident at the crossroads of A and B, etc.) – proximate praxiological location: microco-ordination of activity (I’m feeling his pulse, the wound stretches from elbow to breast, etc.) – virtual location (I’m on the web page x) – socio-emotional significance of location: biographical relevance (I’m at the cottage of x/my friend, I’m driving car with x), cultural significance (I’m visiting x (old church, museum, medieval city, etc.), aesthetic significance (it’s very scenic here) II Praxiological III Socioemotional making arrangements. Most of the calls involve some practical arrangements, in many of which the location of the parties is relevant. Mobile telephony also seems to have shifted the time frame within which appointments are made. Many of the arrangements are made just before the event. Consequently, location is often temporal and prospective, how far the party is from the proposed meeting place. Real-time co-ordination of mobile social action is something that mobile telephony is particularly apt. The socio-emotional location does not seem to be very central in ordinary, everyday mobile calls. It is not that the socio-emotional content (emotional displays) would not take place in these calls, but they are not tied to location but to persons and relationships. The socioemotional location may be far more significant in other contexts such as holiday trips, etc. 6 Implications for location-aware mobile services Taken that practical social arrangements are so commonly made in mobile phone calls, services that would support them would have immense potential. Notably, location is often spatio-temporal and prospectively relevant, i.e. how far a mobile party is from a destination. Location awareness that would also indicate the user’s estimated temporal distance from the destination would have a wide applicability for a majority of mobile users. A simple and usable technical solution would immediately meet the end users’ needs. Real-time co-ordination of social action might benefit from applications created in terms of particularities of this type of action. Real-time co-ordination of social action often takes place in a very limited time frame. Even faster and simpler modes of creating and maintaining contact with the communicative partner than the current modes of mobile telephony might turn useful. Instant mobile messaging systems seem apt for these purposes. There have been a lot of discussions about the inconveniences caused by the fact that mobile devices may be used in troublesome environments. A number of technical solutions have been offered. However, it may be that the users are happy to solve these problems verbally [6]. This study does not support further technical solutions for a user’s interactional availability. Nor does socio-emotional content of locations play a significant role in everyday mobile telephony. New applications augmenting the socio-emotional content may well be relevant in tourist industrial sites and other respective environments. 7 Conclusion The location of the co-conversationalist is commonly relevant during a mobile phone conversation. However, the location is not discussed and does not appear to be relevant in purely geographical terms. Location is made relevant by the activities in which the parties are involved. Joint activities make spatio-temporal location relevant such as distance in minutes from the meeting point via the vehicle used. The precursor for any mutual communication is interactional availability, and the proximal location may have become relevant as a constraint such as being at a dinner table or in a toilet. Extended discussions of location concern mainly its socio-emotional sense, such as its biographical meaning, a place where marriage proposal was made, etc. To put it the other way round, strict geographical location is relevant for mobile conversationalists in only a few cases, such as instructing somebody on how to find place x (and even that may require further explanation beyond geographic location). The design of location-sensitive devices and applications should take into account that pure geographical location is rarely of users’ interest. Acknowledgements I wish to thank Ilpo Koskinen, Esko Kurvinen, Ditte Laursen, Kalle Toiskallio and Alexandra Weilenmann for their helpful suggestions and comments. 323 References 1. Beadle HWP, Harper B, Maguire GQ Jr, Judge J (1997) Location aware mobile computing. In: Proceedings of IEEE/ IEE International Conference on Telecommunications, (ICTi97), Melbourne, April 1997, pp 1319–1314 2. Beigl M (2002) Special issue on location modeling in ubiquitous computing. Pers Ubiquit Comput 6:311–312 3. Satyanarayanan M (2001) Pervasive computing: vision and challenges. IEEE Personal Communications 2001, August 10–17 4. Ling R (2001) Guest editorial: mobile communication and the reformulation of the social order. Pers Ubiquit Comput 5:83–84 5. Ling R, Haddon L (2001) Mobile telephony, mobility and the coordination of everyday life. http://www.telenor.no/fou/program/nomadiske/articles/rich/(2001)Mobile.pdf (26.5.04) 6. BarkhuusL (2003) Context information in mobile telephony. In Proceedings of Mobile HCI 2003, Udine, Italy, ACM Press, pp 1–5 7. Greenberg S (2001) Context as a dynamic construct. Human Comput Interact16(2–4):257–268 8. Dourish P (2004) What we talk about when we talk about context. Pers Ubiquit Comput 8:19–30. DOI 10.1007/s00779– 003–0253–8 9. Barkhuus L, Dey AK (2003) Location-based services for mobile telephony: a study of users’ privacy concerns INTERACT 2003. In: 9th IFIP TC13 International Conference on HumanComputer Interaction, to appear. September 1–5, 2003 10. Kaasinen E (2003) User needs for location-aware mobile services. Pers Ubiquit Comput 7:70–79. DOI 10.1007/s00779–002– 0214–7 11. JordanT, Raubel M, Gartrell B, Egenhofer M (1998) An affordance-based model of place in GIS. In: Spatial Data Handling 98. Conference Proceedings, Vancouver, BC, Canada, July 1998, pp 98–110 12. Laurier E (2001) Why people say where they are during mobile phone calls. Environ Plan D Soc Space19:485–504. DOI 10.1068/d228t 13. Weilenmann A (2003) ‘I can’t talk now, I’m in a fitting room’. Availability and location in mobile phone conversations. In: Laurier E (ed) Special issue on technology and mobility. J Environ Plan A 35(9):1589–1605 14. Atkinson J M , Heritage J (eds) (1984) Structures of social action: studies in conversation analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 15. HutchbyI, Wooffitt R (1998) Conversation analysis. principles, practices & applications. Polity Press, Cambridge 16. Arminen I, Leinonen M (2006) Mobile phone call openings—tailoring answers to personalized summons. Discourse Stud 8:2 17. Schegloff EA (1986) The routine as achievement. Human Stud 9:111–52 18. Schegloff EA (2002) Reflections on research on telephone conversation: issues of cross-cultural scope and scholarly exchange, interactional import and consequences. In: Luke KK, Pavlidou TS (eds) Telephone calls: unity and diversity in conversational structure across languages and cultures. John Benjamins, Amsterdam pp 249–282 19. Schegloff EA (1980) Preliminaries to preliminaries: ‘‘Can I ask you a question?’’. Sociol Inq 50:104–152