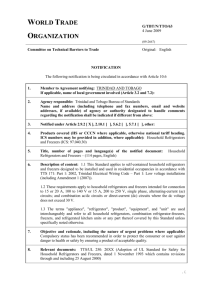

Summary Student Study Guide

advertisement

1 Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................ 3 Section 1 Ecosystem Dynamics and the Status of Ecosystems in Trinidad and Tobago .................. 5 Section 2 Water and Society ............................................................................................................... 10 Section 3 Watershed Assessment and Quality ................................................................................. 12 Section 4 Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) ....................................................... 18 Section 5 Adopt A River ...................................................................................................................... 23 2 Introduction The health and state of a nation’s watersheds are a reflection of the culture and character of its people. At the core of our social and economic functions is water. The dynamic interactions of the demand for water to facilitate human and ecological functions require an Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) approach. The Adopt-a-River initiative, which offers a unique opportunity for the promotion of a better understanding of the impact of environmental conditions and human behaviour on water and society, is premised on the IWRM approach. This initiative facilitates the involvement of schools, civil society and the corporate sector in the holistic, coordinated and sustainable approach to improving the status of our rivers and watersheds. The Summary Student Study Guide is intended to provide a foundation for the study of watersheds in Trinidad and Tobago, and in particular, for students participating in the Water and Sewerage Authority’s 3rd National Secondary Schools’ Quiz Competition ‘In the Know with H20’ on the theme ‘Adopt-a-River’. The challenges of water resource management and measures for restoration of Trinidad and Tobago’s watersheds are addressed in great detail. Ecosystems as building blocks of the environment are strategically introduced in the first section of the manual. A description is presented of the types of ecosystems and those native to Trinidad and Tobago. The biotic (living) and abiotic (mineral) characteristics of ecosystems are examined. The intent is to capture the concept of cyclic flows within ecosystems, including animals, humans and minerals, a rhythm which has been in harmony for millenniums. As a consequence of human development, this synchronisation has become disturbed, creating excessive pressures on the system. An important factor towards understanding the relationship between water and society is exploring the intricate history of the human influence on Trinidad and Tobago’s water resources. This is outlined in the historical uses of rivers, in a less industrialised Trinidad and Tobago. This guide also describes the cultural value of local rivers and waters, including our local folklore. The idea is to remind and in some cases inform on our forefathers use and respect for water. A deeper recognition of the natural elements of a river system is defined by outlining the concept of watersheds. Hydrological theories and water quality parameters are explained to provide a scientific background for watershed assessment. The guide demonstrates the natural water quantity and quality characteristics of a watershed and the tracers that are typically utilised to ascertain anthropogenic changes. The IWRM paradigm, as a possible solution to the stresses placed on water resources, is discussed subsequent to the examination of the scientific and social aspects of water. The discussion highlights the role of IWRM as a best practice approach to the coordinated development and management of all natural water resources. It explains the various aspects of water management and the roles of the human system, regulatory and institutional in achieving the goals of IWRM. The Summary Student Study Guide concludes with a focus on the Adopt-a-River initiative where the project objectives are outlined drawing reference to current local and international watershed improvement projects. The programme aims to discover avenues by which society can become custodians of their waterways. 3 At its core, the Adopt-a-River Summary Student Study Guide will seek to deliver the message of balance between development and conservation, which is desperately needed at this time. The ultimate goal is to share information and empower the society, particularly via the student population, to change their behaviour toward protection of the natural environment and to secure this precious, finite resource, WATER, for present and future generations. 4 Section 1 Ecosystem Dynamics and the Status of Ecosystems in Trinidad and Tobago This area addresses the definition of an ecosystem and identifies the various types and their characteristics. It also seeks to highlight the roles of biotic, abiotic and human factors in an ecosystem. In order to completely understand the role that humans are supposed to place in the environment, we must understand how the environment works. The natural environment consists of ECOSYSTEMS. An ecosystem, short for 'ecological system', includes all the living organisms existing together in a particular area (Sydenham and Thomas 2009). An ecosystem consists of a complex set of relationships amongst the living resources or biotic factors and the non-living or abiotic resources. Biotic factors are the living organisms such as plants, trees, animals, birds, fishes “An ecosystem consists of a and people. The abiotic resources refer to the elements which all organisms need to survive such as oxygen, water complex set of relationships and minerals in the soil. amongst the living resources Although there are different types of ecosystems, most have or biotic factors and the nonsimilar characteristics, which will be discussed further. In living or abiotic resources.” understanding ecosystems and their functions, you must consider that most of the ecosystems are cyclic or better said, part of the „circle of life‟. It is important to know that in a natural environment there is a great deal of dependency among organisms, populations and communities which live in ecosystems. Elements of an Ecosystem 5 Types of Ecosystems There are various types of ecosystems that can be broadly characterized between terrestrial (land) and aquatic (water) ecosystems. Most ecosystem types are natural, though there are a few which are generated from human impacts. These include secondary forests, agricultural lands, freshwater dams and reservoirs. ECOSYSTEMS TERRESTRIAL AQUATIC Mountains Forests Deserts Savannas/Grasslands Freshwater Rivers Ponds Streams Wetlands Marine Seagrass beds Estuaries Coral reefs Salt marshes Hydrothermal vents Figure 1. Ecosystem Characterization Ecosystems in Trinidad and Tobago Trinidad and Tobago hosts a variety of ecosystem types which include forests ecosystems, savannahs, rivers, swamp/mangrove forests (wetlands), and coral reefs. These ecosystems are home to an abundant biodiversity of flora (plants) and fauna (animals) which is unparalleled in the Caribbean. 6 Forest Ecosystem Our forests ecosystems are mostly found in our three mountain ranges: the Northern, Central and Southern ranges. The northern range has the two highest peaks, with El Cerro del Aripo and El Tucuche reaching over 900m (3,000ft). Forests contribute directly to a variety of functions: maintaining the integrity of an ecosystem, providing wildlife habitats, protecting watersheds, mitigating impacts of extreme weather, sequestering carbon, and generating goods and services for direct use by people for consumption, other economic uses, and recreation. It is known that the forests of the Northern Range have continued to be altered as a result of forest clearance for various uses such as housing developments and supporting infrastructure, agriculture, quarrying, and timber harvesting. Forest fires are also a source of forest degradation (NRA 2005). Savanna The Aripo Savannas are a natural savanna ecosystem which in August 2007, was given the designation of Environmentally Sensitive Area (ESA) under the ESA Rules 2001. The Aripo Savanna is dominated by sedges, grasses and herbs as well as a number of rare species including the sundew, an insectivorous (consumes insects) plant. The savannas are the only remaining natural savannah ecosystem in Trinidad and Tobago and has been under threat from quarrying, fires, illegal human settlements and hunting. This has resulted in greater fragmentation of the savanna as well as degradation of the savanna and marsh vegetation. Rivers Rivers are a major source of potable water but are also an important cultural, recreational and a source of food and income to many citizens. For the ease of monitoring and management these rivers are characterised by watersheds, Trinidad and Tobago has 69 watersheds - 54 in Trinidad and 15 in Tobago. One of the major rivers systems is the Caroni River which serves over 40% of Trinidad with potable water. According to the Cropper Foundation, the current status of local freshwater ecosystems is fair but they are being 7 threatened by housing, agriculture, industry, quarrying, chemical and solid waste pollution, alien invasive species and overharvesting. Wetlands A wetland is a land area that is saturated with water, either permanently or seasonally, such that it takes on characteristics of distinct ecosystems. Wetlands in both Trinidad and Tobago have undergone significant alterations especially on account of human activities. Significant losses have occurred along the west coast of Trinidad (including the Caroni Swamp), on the east coast of Trinidad (Nariva swamp), and in south-western Tobago (Institute of Marine Affairs, 2010). Opadeyi (2010) reports a decrease of 17% in the extent of wetlands in Trinidad. It has been estimated that the Nariva Swamp has seen 17% reduction in the size. This is an environmentally sensitive area and an internationally recognised Ramsar site, but as a result of rice farming activities, slash and burn agriculture and infrastructural development (Carbonell et al 2007) there has been a loss of approximately 135 hectares. Coral reefs Coral reefs are often referred to as the “rainforests of the sea” since they support the most diverse ecosystem on earth. This complex system acts as the first natural defense against high energy waves protecting the shoreline from wave damage and coastal erosion. They are also important to the local economy attracting tourists as well as a nursery for fishes. Reefs are sensitive to small changes in the environment such as sediment, nutrients and temperature. Though these parameters change naturally, man’s influence has increased the rate of change which negatively affect this ecosystem thus reducing their beneficial capabilities. Man-made Systems There are a number of man-made systems as well, which include secondary forest, agricultural lands, freshwater dams and reservoirs. 8 ECOSYSTEM PROVISIONING SERVICES Timber FORESTS INLAND FRESHWATER SYSTEMS (rivers and streams) COASTAL / MARINE SYSTEMS Non-timber forest products (including wildlife, handicraft and medicinal plants) Tropical forest biota i.e. game species and species used in the pet trade Freshwater sources in land fisheries, species for the pet trade; Aquaculture Aquatic species used in the pet trade REGULATING SERVICES Runoff regulation and retention Biodiversity services (population regulation, habitat and species diversity) Soil conservation; Soil formation and fertility; Climate and microclimate regulation; Atmospheric composition regulation Waste disposal, assimilation and treatment (for the provision of freshwater) Flood regulation, water storage Biodiversity services (population regulation, habitat and species diversity) Marine fisheries (including other coastal and marine products e.g. oysters, shrimp, crabs) Other food (wildlife, agricultural products) Coastal and wetland resources (eg. from mangroves) Ornamental marine, brackish water species Waste disposal, assimilation and treatment (regulation of coastal water quality) Flood regulation/ water storage MAN-MADE SYSTEMS Agricultural products: crops and livestock (Agricultural, reservoirs) Water storage Provide variations on natural habitats well as new niches Soil conservation; Soil formation and fertility; Climate and microclimate regulation; Atmospheric composition regulation SUPPORTING SERVICES Water cycling and replenishment of surface and ground water resources Biodiversity support (pollination, germination, dispersal, food webs, productivity, terrestrial/aquatic ecosystem interface) Nutrient cycling and transport Biodiversity support (food webs, productivity, terrestrial/aquatic ecosystem interface) Nutrient cycling and transport Biodiversity support (food webs, productivity, terrestrial/aquatic ecosystem interface) Nutrient cycling and transport Shoreline protection (provided by coastal ecosystems such as mangroves, coral reefs and seagrass beds) Climate and microclimate regulation Biodiversity services (population regulation, habitat and species diversity) 9 Biodiversity support (food webs, productivity, terrestrial/aquatic ecosystem interface) Nutrient cycling and transport Section 2 Water and Society This theme describes the historical use of water in Trinidad and Tobago as well as its influence on our culture, communities and beliefs. Amerindian societies, like many civilizations throughout history, were strategically located near water courses to quench their need for water to drink, acquire food (fishing), transportation and washing their clothes and themselves. The rivers were the only reservoirs of freshwater in those times. The rivers that our forefathers knew were much larger than they are today. Ships and canoes were the major modes of transportation and aided in the discoveries of many of our towns as villages. In 1592, under the Spanish flag, a ship sailed up the Caroni River and turned into a tributary, now known as the St Joseph River, the first capital of Trinidad was founded and called San José de Oruňa. The Lopinot River once transported a great deal of cocoa from the estates high in the hills to the main road and then into Port of Spain. One of the first efforts in the conservation and protection of water sources in the western hemisphere was the establishment of the first forest reserve in Tobago in 1765. The Colonials reserved this area for the “protection of the rains” and their direct environmental benefits. The dawn of the industrial age saw the distribution of water go underground and out of sight. In 1853 the Maracas Waterworks became the first organized distribution system in Trinidad and Tobago. It served the purpose of granting 25,000 people that lived in Port of Spain, at that time, pipe borne water. There was no need to live near the source; pipelines were established to bring water to your home no matter how far you were from a source. Humans now controlled its supply and distribution. New technologies ensured accessibility to the masses. 10 DID YOU KNOW? The Dial, the most famous landmark in Arima, when installed used machinery which was powered by a stream that flowed through the town. Maraval waterworks in the 1850’s Water bodies have long since been the gathering place for cultural activities as well as for more social gatherings. From the Hindu festival of Ganga Dhaaraa to the local “river lime”, people of Trinidad and Tobago have always gone to water bodies for spiritual mediation and recreational purposes. These activities have also left a negative effect on our water bodies; litter and garbage are left after these events that clog the water ways contributing to flooding and diminishing the aesthetic appeal of the area. In Trinidad and Tobago we feel entitled to water because it is so easy to access. We can bring it into our homes by merely turning on a faucet. This means that we tend to take cheap, abundant, good quality water for granted. This situation describes the theory of „Tragedy of the Commons’. It describes an ongoing condition of unsustainability that arises when a shared resource is continuously depleted even when it is in the best interest of all to prevent this from happening. Without responsible use, our water resources can be severely affected. Water has also stretched into our folklore, "Mama Glow" or "Mama Dlo" or "Mama Dglo" whose name is derived from the French "maman de l' eau" which means "mother of the water" is one of the lesser known personalities of Trinidad and Tobago folklore. A half woman, half snake with long flowing hair which she combs constantly. Her upper torso is a naked, beautiful woman, the lower part coils into a large form of an anaconda snake that is hidden beneath the water. She is sometimes thought to be the lover of Papa Bois, and old hunters tell stories of coming upon them in the 'High Woods'. 11 Section 3 Watershed Assessment and Quality This area identifies watersheds in Trinidad and Tobago and their status. It also explains the parameters of assessment and effects of land use change on their condition. A watershed is defined as “The area of land where all of the water that is under it or drains off of it goes into the same place” United States Environmental Protection Agency, (USEPA) It is also considered as an area or region drained by a river, river system, or other body of water which is separated by an area or ridge of land that prevents waters from flowing into different rivers or basins (Oxford Dictionaries). Figure 2 illustrates the concept of watersheds as defined above. All the water moving through the area of land eventually accumulates at a lower point. The watershed is also bound by ridges on either side from its upper to lower reaches. This physical barrier prevents any interaction with other watersheds. Trinidad and Tobago is subdivided into fourteen (14) hydrometric units, nine (9) in Trinidad and five (5) in Tobago. Trinidad is further sub-divided into 54 catchment areas (watersheds) and Tobago sub-divided into 15 catchment areas (watersheds). DID YOU KNOW? One of the most critical watersheds in Trinidad and Tobago is the Caroni Basin, which serves as a source for about 40% of the country’s potable water and is one of the most polluted and is one of the most polluted. Figure 2. A conceptual diagram of a watershed. 12 Maps showing the Hydrometric Areas and Watersheds of Trinidad and Tobago (Genivar, 2009) 13 The important thing about watersheds is what we do on the land and how it affects the quality and quantity of water for all communities living downstream. Healthy watersheds provide food and shelter for wildlife as well. Watershed management is the process of creating and implementing plans, programs and projects to sustain and enhance watershed functions that affect the plant, animal and human communities within the watershed boundary. Some of the features of a watershed that agencies seek to manage include water supply, water quality, drainage, storm water runoff, water rights and the overall planning and utilization of the watersheds. Watershed assessment is a necessary component of a monitoring program in order to determine what degraded or impaired areas may exist in the watershed and why. Several characteristics of a watershed are taken into consideration during the assessment process including land use, land cover, hydrology and biodiversity. It is important to also consider the natural and cultural resources of the watershed as well as the human activities. This information may be obtained from various sources including topographic maps to determine drainage area and land features as well as land use data (North Carolina Cooperative Extension). Watershed assessment is also an efficient and cost-effective means of evaluating and categorizing water quality. It provides valuable information for use in community planning, identification of pollution sources, and maintenance of the health and aesthetics of a water body (Watershed Assessment Associates, 2001). Land use Issues in Watersheds There are several different land uses in a watershed: natural vegetation, deforested/clear-felled, agriculture, industrial and commercial and residential. Each of these uses can impact on the dynamics of a watershed. In addition to processes within the watershed, land-use changes also affect its physical and biological makeup. DEFORESTATION Definition: the clearing of forests and removal of trees (e.g. quarrying) and other vegetation for agricultural, commercial, housing or firewood uses without replanting (reforesting) and without allowing time for the forest to regenerate itself. Impacts: soil erosion, reduced soil absorption of rainfall, reduction in water availability, increased runoff (flooding), landslides. Affected watersheds: Arima, Guanapo, Mausica, Santa Cruz, St Joseph, Tacarigua, Courland 14 AGRICULTURE Definition: The science or practice of farming, including cultivation of the soil for growing of crops and the rearing of animals to provide food and other products (Oxford Dictionary, 2011). Impacts: high nutrient levels (fertilizers), reduced oxygen (increased algal bloom resulting in fish kills), and heavy metal contamination (pesticides) i.e. reduced water quality for human consumption. Affected watersheds: Aripo, Guanapo, Arima, Tacarigua, Maracas, Talparo, INDUSTRIAL/COMMERCIAL Definition: a particular form of economic activity concerned with the processing of raw material and manufacture of goods in factories. Impacts: industrial effluent, notably synthetic organic chemicals, heavy metals Affected watersheds: Mausica, Tacarigua, Arouca, Couva, Guaracara, Caparo, South Oropuche, Guapo, Erin URBAN DEVELOPMENT/SPONTANEOUS SETTLEMENTS Definition: the expansion of communities, towns and cities into natural areas such as, forests, flood plains and swamps. Impacts: the same impacts as deforestation and includes, domestic wastewater, urban runoff, solid waste (bottles, and other garbage thrown in waterways) Affected Watersheds: Mausica, Guanapo, Santa Cruz, Tacarigua, Couva, Nariva, South Oropuche, Erin, Aripo, Cunupia, Cumuto, Talparo, Courland 15 Water Quality Pollution is the contamination of the earth‟s environment with materials that interfere with human health, the quality of life or the natural functioning of the ecosystem. Water pollutants can be classified into three types: solids, liquids and gases. Solid pollutants would be garbage and trash that we litter our rivers with for example, old fridges and cars. Domestic wastewater or untreated water from our sinks and toilets are examples of pollutants. Gaseous pollutants include steam which is a waste product of industrial processing. There are many parameters which are used to assess water quality. Some of the more commonly measured parameters are as follows: TOTAL SUSPENDED SOILDS (TSS) CONDUCTIVITY (COND) pH TSS are solid materials that are suspended in the water which result from erosion from urban runoff and agricultural land, industrial wastes, bank erosion, algae growth or wastewater discharges (NDDH 2005). High concentrations of suspended solids gives water a brown colour and blocks out light, thus preventing the growth of aquatic plants, reducing the oxygen in water and kills aquatic organisms e.g. fish and crabs. Conductivity is a measure of the ability of water to pass an electrical current. It is affected by the presence of inorganic dissolved solids in the water. Organic compounds like oil do not conduct electrical current very well and therefore have a low conductivity in water. Conductivity is also affected by temperature: the warmer the water, the higher the conductivity (USEPA 2011). pH is a measurement of the acidity or alkalinity (base) of a solution. pH is measured on a scale of 0 to 14. Neutral water has a pH of 7. Low pH values in freshwater are also caused by the dissolution of acids-forming substances in precipitation. Pure rainfall has a pH of about 5.6. High organic matter content in the water will also decrease the pH of water. 16 DISSOLVED OXYGEN (DO) TURBIDITY (TURB) FREE AMMONIA Dissolved oxygen analysis measures the amount of gaseous oxygen (O2) dissolved in an aqueous solution. Oxygen gets into water by diffusion from the surrounding air, by aeration (rapid movement), and as a product of photosynthesis. Oxygen levels that remain below 1-2 mg/l for a few hours can result in large fish kills (KY Water Watch 2011). Dissolved oxygen values locally ranged from 0.6 to 8.2mg/L. Turbidity is a measure of the degree to which the water loses its transparency (Lenntech 2011). There are various parapeters which influences the cloudiness of the water. It is measured in NTU: Nephelometric Turbidity Units. The instrument used for measuring it is called a nephelometer or turbidimeter, which measures the intensity of light scattered at 90 degrees as a beam of light passes through a water sample (Lenntech 2011). The term free ammonia refers to NH3. It is highly reactive and can affect the health of organisms, including humans. Ammonia is an indicator of faecal (sewage) pollution. It affects the taste and smell of water and makes disinfection more difficult (WHO 2008). Ammonia in the environment can originate from metabolic, agricultural and industrial processes, from disinfection with chloramines, fertilizer runoff and sewage release (Bellingham 2011). NITRATES Nitrate ion (NO3-) is the common form of nitrogen in natural water (Bellingham 2011). Natural sources of nitrates include igneous rock, plant decay and animal debris. Nitrate levels over 5mg/L indicate man-made pollution which includes fertilizers, livestock, urban runoff, septic tanks and wastewater discharges. In general, nitrates are less toxic to people than ammonia or nitrites however, they are toxic to infants. In the environment, nitrate will become toxic to fish at about 30 mg/L. Nitrate pollution will cause eutrophication or algal blooms where algae and aquatic plant growth will consume the oxygen and increase the TSS of the water (Bellingham 2011) 17 Section 4 Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) This area describes the role of IWRM as a best practice approach to the coordinated development and management of all natural water resources. It explains the various aspects of water management and the roles of the human system; legislative institutional and stakeholders, in achieving the goals of IWRM. In 2000, freshwater became redefined as a finite and vulnerable resource, especially to sustain life, development and the environment (GWP TAC 2000). This redefinition became necessary due to the increase in global population size, increased economic activities and improved standards of living, which lead to increased competition for and conflicts over limited freshwater resources. Trinidad and Tobago is not a water scarce nation. According to the World Bank water requirement criteria, the minimum water availability to sustain human life is approximately 1000 cubic meters per capita per year. Trinidad and Tobago has an annual average water production of 2500 cubic meters per capita per year (GOTT, 2007). However, the availability, accessibility and quality of water do not coincide with the location and needs of the citizens. Dublin Principles In January 1992, at the International Conference on Water and the Environment (ICWE), Dublin Ireland the Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development also known as the “Dublin Principles” was adopted. This conference was the last technical preparatory meeting before the UN Conference on Environment and Development (the “Earth Summit”) in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992. The Dublin Principles have been the basis for much of the subsequent water sector reform, they are as follows: 1 Fresh water is a finite and vulnerable resource. 5 3 4 Role of women. 2 Water Management has to involve all stakeholders. Water has a Social and economic value. Integrating the three (3) E’s: economic efficiency, equity and environment 18 Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) “IWRM is a process that promotes the coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources, in order to maximize the resultant economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems” (GWP-TAC, 2000) The IWRM approach promotes a coordinated development and management of land and water, surface water and groundwater, the river basin and its adjacent coastal and marine environment, and upstream and downstream interests. The concept of Integrated Water Resources Management - in contrast to “traditional”, fragmented water resources management - at its most fundamental level is as concerned with the management of water demand as with its supply. IWRM has gained worldwide acceptance as a successful way to tackle the challenges associated with water resources management. Thus, integration can be divided into two (2) basic categories: The natural systems, with its critical importance for resource availability and quality. The integration of the natural systems, such as freshwater systems and the coastal zone; land and water; surface and groundwater and the upstream and downstream interests. The human systems, which fundamentally determines the resource use, waste production and pollution of the resource, and which must also set the development priorities. This would include national integrated policy development, influencing the economic sector, integration of ALL stakeholders and the integration of water and wastewater management. IWRM explicitly challenges conventional, fractional water development and management systems and places emphasis on an integrated approach with more coordinated decision making across sectors and scales. This integrated approach to water management is not a one shot approach but a process that achieves three (3) key strategic 1. 2. 3. objectives: Efficiency to make water resources go as far as possible Equity in the allocation of water across different social and economic groups Environmentally sustainable, to protect the water resources base and associated ecosystems. 19 The three pillars of IWRM as stated by the Global Water Partnership are: Moving towards an enabling environment of appropriate policies, strategies and legislation for sustainable water resources development and management; Putting in place the institutional legislation can be implemented; and framework through which policies, strategies and Setting up the management instruments needed for effective regulation and enforcement, conflict resolution and information exchange. IWRM is a process and should not be considered a one-shot approach. It is one that is long-term and forward-moving but iterative rather than linear in nature. It is a process of change which seeks to shift water development and management systems from their currently unsustainable forms; IWRM has no fixed beginnings or endings Cross-Sectoral Integration ENABLING ENVIRONMENT INSTITUTIONAL ROLES Water for people Water for Food Water for Nature Water for industry and other uses MANAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS Figure 3. IWRM and its relations to sub-sectors (“GWP Comb” Taken from GWP, 2002) 20 In the IWRM process there are some vital components that must be included in the management framework, the Components of IWRM: Managing water at the basin or watershed, this includes integrating land and water, upstream and downstream, groundwater, surface water, and coastal resources. Optimizing supply, this involves conducting assessments of surface and groundwater supplies, analyzing water balances, adopting wastewater reuse, and evaluating the environmental impacts of distribution and use options. Managing demand, such as adopting cost recovery policies, utilizing water-efficient technologies, and establishing decentralized water management authorities. Providing equitable access, that supports effective water users’ associations, involvement of marginalized groups, and consideration of gender issues. Establishing policy, examples are implementation of the polluter-pays principle, water quality norms and standards, and market-based regulatory mechanisms. Utilizing an intersectoral approach to decision-making, where authority for managing water resources is employed responsibly and stakeholders have a share in the process. Trinidad and Tobago is still far from being fully immersed into the integrated approach to water management; however we have taken strides in this direction. Current legislation places the responsibility for water planning, management, conservation and protection of the water resources under the ambit of the Water and Sewerage Authority (WASA), (WASA Act [1965], Part III Sections 42). The Water Resources Agency (WRA), a department within WASA, has the responsibility for monitoring and managing the watersheds in Trinidad and Tobago. 21 In 1987, WASA established a Water Resources Committee in recognition of the need for an integrated approach to water management in Trinidad and Tobago. This Committee consisted of representatives from various governmental organizations and private sector groups, whose activities impact on water. One of the most important achievements of this committee was the preparation of a draft Water Management Policy, known today as the Integrated Water Resources Management Policy (2005) This Policy was approved by cabinet in 2005 seeking to establish the foundation of IWRM in Trinidad and Tobago. This policy speaks to the integration of sectors and maps the way forward towards an improved legislative framework for water management. The policy provides an overview of the status of the country‟s water resources and outlines the goal and objectives of water resources management. One of the major milestones in the water sector was the establishment of the Integrated Water Resources Management Stakeholders Meetings in November 2009. Since then, there have been 10 general meetings and several sub-committee meetings. This elite group composes of over thirty (30) representatives from Governmental Organizations, NGOs and CBOs that come together every quarter to discuss and implement the way forward in water resources management. The members of this group have gained a better understanding of the IWRM principles and the philosophy that it adheres to. Coming out of these meetings have been projects to improve our watersheds, water quality and the public perception and understanding of water related activities. Water resources management is critical to the well being of the country. However, water resources cannot be managed in isolation of the environment. The delicate balances between securing water for people, food and ecosystems, while maintaining the long term sustainability of the water resource must involve the management integration of the interdependent water, land Management of the environment is the actual key to sustainable water resources management. and ecosystems. 22 Section 5 Adopt A River This theme explains the Adopt A River project, which is an initiative to involve the community and corporate citizens in the improvement of watersheds in Trinidad and Tobago in a sustainable, holistic and coordinated manner. It details the process of Adopt A River and describes the project initiatives while drawing reference to current watershed improvement projects both locally and internationally. The Adopt a River project is an initiative to involve the community and corporate citizens in the improvement of watersheds in Trinidad and Tobago in a sustainable, holistic and coordinated manner. Due to the increase in the pollution of the rivers, fragmented management and institutional frameworks as well as the exclusion of citizens in the management process, the Adopt A River Program will encourage the active participation of stakeholders within the river basin at all stages of the program life cycle. Stakeholders will design and implement projects that are applicable, implementable and sustainable, therefore, promoting a sense of ownership of the watershed and encouraging a commitment towards its rehabilitation and conservation. This community and issue-based approach has been the recommended path for the implementation of IWRM in Small Island Developing States (SIDS), such as Trinidad and Tobago. this will more readily lead to an action strategy based on tangible and immediate issues. It has also According to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), been shown that such an approach can help win broad public support. The logo (Figure 4) created for the Adopt A River Program is the local fish species Poecilia reticulata or Guppy. This is a very common local species of fish which is known for being able to adapt to adverse environmental conditions. It was chosen because it is very well-known and also The common name of this fish (Guppy) was actually taken from a Trinidadian, Robert John Lechmere Guppy, who discovered this fish locally in 1886. As such, it has great significance locally and makes a because of its survivorship. favourable mascot for the Adopt A River program. Figure 4. The Adopt A River Logo 23 The overall objective of the „Adopt a River‟ program is to bring awareness to local watershed issues and to facilitate the participation of public and private sector entities in sustainable and holistic projects aimed at improving the status of rivers and their watersheds in Trinidad and Tobago. The specific objectives to be achieved by the WASA program are: Educating citizens of all sectors on the water pollution issues locally, how they contribute towards the problem and how they can help Fostering appreciation for the natural environment and by extension national pride whilst maintaining an open, sharing, facilitating atmosphere within the „Adopt a River' project Promoting a volunteerism ethic to benefit all levels of society Empowering all users of water - private and public sector agencies, communities and schools - to protect water resources and participate in water resource management Facilitating the involvement of patrons and sponsors in stakeholder empowerment and resource management strategies Developing and making available the necessary tools for training and empowering local implementing agents and other role-players Ensuring optimum efficiency through involvement and linkages with other existing programs and water resource initiatives. Managing the initiative towards achieving a change in culture and behaviour towards sustaining the health and aesthetics of a river 24 The Adopt A River (AAR) process consists of ten (10) simple steps. 25 The initiatives under AAR can be either direct (active participation) or indirect (funding or sponsorship) projects. The participants are encouraged to adopt either an entire watershed or a part thereof and work within these areas, implementing any of the suggested projects. The adopter can also design their own project for implementing within their watershed of adoption; however, this project should meet at least 3 of the objectives of the overall program and fall into the following project areas: Education Education is the foundation on which the following projects will be successful. Educational programs would include: School visits and lectures Community-based lectures and outreach programs Television and radio Websites Employee initiatives Reforestation, repopulation and rehabilitation Exercises Since deforestation has been identified as a major cause of water pollution and flooding, especially in the Northern Range (NRA 2005), tree-planting exercises can be done in catchments of greatest concern. Lack of vegetation along watercourses and its poor management has been identified as an important contributor to increased erosion and sedimentation of rivers (Maharaj and Alkins-Koo 2007) therefore, it is very important to implement a reforestation program, not only on river banks but also on deforested slopes and plains which become denuded regularly during the dry season. Cleanup Projects This involves regularly cleaning up the watersheds to ensure that garbage or debris does not block waterways and encourage flooding. It would include regular clean-up exercises, landscaping and the establishment of proper waste disposal facilities as required. One possible example of a clean-up exercise would be a ‟River Clean-up Lime‟ where persons walk a particular length of a river, cleaning as they go and arrive at a particular point at which food is being prepared as in a „river lime’, just in time for lunch. One advantage of adopting a river in this manner is the possibility of using the adopted area for retreats and company functions such as family days. 26 Water Monitoring Programs Since there is a need for continuous monitoring of our rivers, baseline water quality monitoring can be included aside from clean-up and tree planting exercises. A very good example of a community-based monitoring program is the ProEcoServ project which is being implemented by the Institute of Marine Affairs. Under this project, community and farming groups from the Caura/Tacarigua area have received training in water quality monitoring so that they can conduct monitoring exercises and also act as trainers in their communities (IMA 2011). School Involvement and Competitions Schools can be involved in the „Adopt a River’ drive in a number of ways: Tree Planting Exercise - Schools can participate in a tree planting exercise at least once per academic year. School Water Conservation Competitions - A school water conservation competition can be launched where the school with the most impressive, inexpensive water recycling model wins. This system will be completely functional and a permanent addition to the infrastructure at the school with no threat to safety of the students. Community Based Projects and Competitions With community visits and exchange, a level of trust can develop between communities and adopters. This would facilitate the easy exchange of information about the water related issues amongst the participants so that adopters and communities can work together to resolve them. Voluntary Effluent Cleanups In most rivers industrial, agricultural and domestic effluents are major sources of contaminants. Hence, companies or individuals can become involved in the Adopt a River activities by voluntarily cleaning up their effluents before release. In many cases, companies which release their effluent into rivers have little knowledge or understanding of their impacts on downstream activities. For example, the Mausica River and Tacarigua Rivers receive effluents from industrial and residential areas and are still used by farmers to irrigate crops. 27