caesar's construction of northern europe: inquiry, contact and

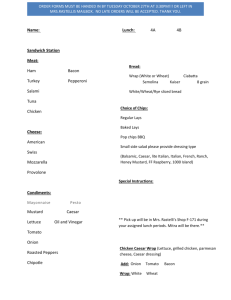

advertisement