Psychoactive Substances and Paranormal Phenomena: A

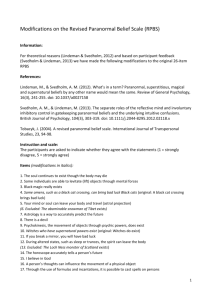

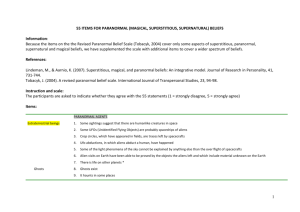

advertisement