Listen, Learn, Link - Intranet

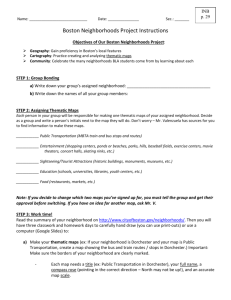

advertisement

Listen, Learn, Link Louise Blalock, Chief Librarian, Hartford Public Library To provide corltext for the rneetiiig, this report begins with arr essay by Louise Blnlock, of the Hartford Prrblic Library, iin Cor7riecticirt, an ACCESS partner and a leader in rejrlverlntirlg the 1rrba11library and its city tlzrough a n emphasis on brancll libraries a~zdtheir neighborlioods. Altlzo[rgli Hartford's innovative approach arose independerztly of LFF's ACCESS initiative, it springs Forn the same desire to bri~zg thr library and its commrrlzity into the closest possible relntionship. Introduction Nothing is more important than bringing back our cities, and the public library is crucial in this effort. Hartford Public Library serves a small city, but we have the same urban problems as larger cities. Hartford's unemployment rate is twice the national average. Nearly 50 percent of all children (18 years of age and under) live below the poverty line. In a non-presidential election only 25 percent of the registered voters go to the polls. Ninety percent do not vote on the issues even when they directly affect their neighborhood. Although libraries by themselves cannot solve community and societal problems, they can contribute to the solutions: about finding jobs; about teen pregnancy; about the quality of life; about countering a pervasive discouragement. My core operating principle is, "The genius of the public library is i n meeting the individual wherever they are in their lives." "Today's challenge is to reinvent the library to respond to community needs and aspirations, and yet to retain the core values of intellectual freedom, flee and equitable access, and trust and mutual respect." Today's challenge is to reinvent the library to respond to community needs and aspirations, and yet to retain the core values of intellectual freedom, free and equitable access, and trust and mutual respect. The social change we are experiencing is as powerful as the technological change, and equally a driving force in the need to reinvent ourselves. How do we do that? By getting as close to the community as we can, paying attention to what they say, and participating in community organizations: listening, learning, linking. This is a mutual process. We must help people to express their need for information, for learning, and for cultural sharing, because although these needs exist, they too often remain unexpressed. We must create the library services that will give them what they have been wanting all along, and to make those services both strikingly apparent and easily used. We must create services that customers truly value but may never have thought to ask for! We must niake the connection between the library and people - issues like workforce preparedness, civic life, and equitable access to telecommunications. And while we do this, we at the library are gaining a new capacity and competency, which is what empowerment is really about: building skill and confidence. The library gets its vitality from the neighborhoods. Organizations run down unless they bring energy in from the outside. We need the energy from our community and we need to take the energy we bring in and transform it with our responsiveness and creativity. We must leave the "library box" and move beyond bibliographic control to life-coping. Children alone? Elderly alone? Homeless? Jobless? Sick? Blue? We need to look social change as squarely in the eye as technological change, freeing up resources to assist users in new ways. We a t Hartford have begun putting this belief into practice through our Neighborhood Teams. Listen, Learn,Link a Neighborhood Team Concept A year ago, staff at the Hartford Public Library established teams for the seventeen neighborhoods of the city. The goal is to identify and respond to opportunities to provide library and information services through new initiatives, as well as to raise the library's capacity to serve the neighborhoods by working in collaboration with agencies and community groups such as the Hispanic Health Council, Habitat for Humanity, the Science and Sports Charter School, or Literacy Volunteers of America. The teams are united by a vision created by the team leaders - usually a community librarian - which gives certainty and purpose to the effort. Each team has five to six members, including a community librarian, a children's librarian, a staff member who lives in the neighborhood, and staff members with a relationship to a community organization or agency of the neighborhood. The number-one job is to know the neighborhood. Who are your people? What are the issues? What are the organizations? Who leads them? Does the library have a positive presence in the neighborhood? How is it serving the interests and needs of people? As they move through the neighborhood, team members listen to learn, and listen to lead. They are advocates for the library and its ability to contribute to the quality of life. Through the neighborhood teams it is more possible than ever before to link people wherever they live in the city to the total resourcc:s of the Ilibrary system. Because we are connecting stal:i to staff with a new sense of purpose, a powerful communications exchange and a dynamic intervention into the whole structure of the library's operation is taking place. Background The concept of neighborhood teams evolved -from the library's participation on the city's Neighborhood Problem Solving Committees (PSCs), which were developed as part of 2 community-policing initiative with a major grant from the U.S. Department of Justice. I was fairly new to the city, having become director of the library in 1994, and eager to learn about the neighborhoods. I was also concerned and puzzled that although the branches consistently accounted for 45 percent of the total activity, they did not produce much reference and information activity. I believed that working with the PSCs was a way to learn about the real interests and needs of the neighborhoods, to be more responsive, and to better meet community information needs. Heod to the Library Day, Central Library The Branch Services Manager was immediately enthusiastic about working with the PSCs, and together we got community librarians to join in meeting with the neighborhood problemsolving groups. We learned quickly that people wanted information o n quality-of-life issues such as jobs, housing, tenant rights, parenting, child care, schools, safety, citizenship, and a range of community issues like noise abatement, litter, prostitution, abandoned buildings, and drug dealing. We responded by developing a community information database and integrating community information into the bibliographic database. We also learned that the sources for interactive information that help people to understand and address community and quality-of-life issues are the very people and agencies in other communities who have developed working solutions, suggestions, and ideas. Connecting with people in other neighborhoods locally, re,'a ~ o n ally, and nationally requires access to the Internet's electronic bulletin boards, web-browsing capability, and electronic mail. With grants from Microsoft and the Gates Library Foundation, we began Neighbors on the Net to provide access to information, resources, and Internet capability, and the training and assistance that users require to address real-life issues. Two neighborhood technology centers are now up and running and two more will be opening soon. We also created a progressive program for Family literacy that has become the genesis for family services for the entire library cListen, Learn. Link system. The five-part literacy initiative both reinvents our services and renews our commitment to children and their parents. b7ithin a year of working with the PSCs, the library was on the agenda for a $16 million bond issue to expand the Central Library and to renovate three of the nine branches. In the two months leading to the vote - heavily in favor of the capital project - I visited more than 50 grassroots neighborhood organizations. And 1 learned a lot. Together with my experience with the PSCs, I became convinced that more people in the library need to be out there in the city, listening, learning, and linking the library's expertise and resources to people, associations, and agencies in the neighborhoods. In 1997, staff discussion and a staffdeployment study brought us to realize that we would not meet the goal of building community and connecting the neighborhoods unless we rethought our community library services. Staff were concentrated in the Central Library and staffing was basic, minimal, thin in the nine neighborhood branches. It was difficult to get out of the library box and into the community. We took a new look at the totality of staff resources, a new way of looking at our world. We had a tendency to define answers as Central Library or branches. And Neighborhood Teams were born. Implementation We began by matching branches to neighborhoods. We also inventoried staff and community agencies. We quantified time commitment and identified staff responsibility; and we created a schedule flexible enough to permit staff to participate fully. We made team assignments, established priorities for community affiliations, set a framework for team structure and communication, and planned for both team training and advocacy training. Sixty people, nearly 50 percent of the total staff, joined a two-day training and team-development session and kick-off. The workshop focused on moving from a "collection of people" to the high-performance synergy of a "Dream Team." We learned about dealing with conflict, working to move from a view of conflict as destructive to conflict as problem-solving. We aimed for common goals, high morale, and high productivity. Each team developed initial goals. We wanted the team to identify community interests and needs and to be innovative and show initiative. We expected the team to give evidence of its involvement in the community. We wanted substantive press coverage, community recognition, and, not least but first, greater use of all libraries, including the new Library-on-\\'heels which is on the road in all the neighborhoods. We wanted to speak about our resources and expertise in concepts people readily understand, like family literacy, Homework Centers, and Neighbors on the Net. And we needed to be holistic. Libraries are great providers for consumer health, but it is not enough to know the material: we also need to know the health providers, organizations, and health issues. Hortlord Conservotory Alusicions at the Asylum Hill/West End Open House "Information" as it's usually thought of does not deal, of itself, with the issue of teenage pregnancy, for example. This is a self-esteem issue. We also need to understand how we are contributing to youth self-esteem. Is the librarian who selects health materials an advocate for helpful, responsive, respectful behavior and communication with teens? Is the librarian well connected to the health network? We need take the initiative with the teenagers who may need stories and experiences that will bestow self-esteem more than birth control information. Teenagers helped us to define amenity. Teenagers have a hard time talking about the library, but they will and do talk about themselves and their community. This is how the kids we talk to describe the city: "Just another inner city." "It needs more heart." "Homeless children." "Parents who have no way, no money to take care of their kids." "The drug problem is horrendous." "The streets are paranoid." "People are killing themselves, killing the community." "There's a statue of justice [at the Old State House] and she's blind!" Listen. Learn, Link , - Asked what they want for their city, they answer: "One-on-one with people" about employment, drugs, personal safety, better schools. About parks and flowers. About life and family education for their mothers. They ask: "Can we make housing more beautiful? Not just affordable, but can we get help with taking care of the housing?" They say, "If only there were more caring adults!" Operating Principles Each team's membership remains in place for 12 months to foster cohesion and enable members to explore the neighborhood, network and build partnerships, and deliver responsive programs and services. Each team meets monthly, and Team Leaders meet bi-monthly. Meetings provide Team Leaders with support and training as they acquire the skills to manage teams and the team process. All team members are expected to establish a connection with a community organization and attend meetings regularly. The children's librarian, for example, might adopt a parents' organization; a staff member who lives in the neighborhood might join the Neighborhood Revitalization Zone committee. The teams are non-hierarchical and include both support staff and librarians, public service and non-public service staff. Attending meetings and working with community organizations is part of the normal work week. Members are entitled to adjust their schedules for attendance at community meetings that occur outside of normal work hours. The secretary for each team keeps a calendar of team meetings, community meetings, and new services. Twice a year, the Team Leaders make a presentation at the managers' meeting. Every member gets the opportunity to reflect o n the Neighborhood Team experience and to offer feedback to the Associate Librarians, Branch Manager, and Children's Services Manager. Each team meets once a year with the Chief Librarian to share experience, assess progress, and plan the coming year. A community librarian who is also a Community Services Deputy Manager and a Reference Librarian leads the Task Force for the Neighborhood Team Project. Working with the Chief Librarian and key managers, and with the assistance of a project management consultant, the Task Force develops a comprehensive work plan to meet four objectives: organize teams; communicate the purpose and benefits of Neighborhood Teams to all staff; conduct an ongoing assessment of neighborhood trends, changes, and events; and respond promptly to changes in neighborhoods to ensure that services meet needs. For each objective, strategies or tasks are set down, action steps are determined, completion dates and projected responsibilities are established, and, most important, measures of success are identified. Results to the Library Day, library The branches and Central Library are meeting customer expectations for timely and accurate information, books, and other materials, and for a safe, pleasant, and hospitable neighborhood library. As advocates for the neighborhoods, Team Leaders are bringing back to the library the experience of people in the neighborhoods, calling our attention to interests and needs both easy and con~plex,from working printers to literature from the West Indies. Teams are talking with neighborhood leaders, and also with staff from city departments. All teams have taken walking tours with neighborhood leaders, lunched at neighborhood restaurants, and gotten acquainted by attending the meetings of Neighborhood Revitalization Zones, Problem-Solving Committees, and merchant and civic associations. Each team has gathered data to update the neighborhood profile, documenting relationships, noting trends, and stating the issues. Team members are on school governance committees, chairing neighborhood association meetings, taking the lead in community activities, out in front for neighborhood events. Our staff letter, "Listen, Learn, Link," is full of stories about what is happening in the neighborhoods. p -Lis:en, Lecrn, Link Three efforts hold particular interest because of their promise to grow, multiply, and keep making a difference. Story #1 A merchants association wanted a business reference collection, but it was not feasible to duplicate Central Library resources at a branch. After meeting with the Business and Reference staff, we came up with the idea of networking resources as the way to achieve the objective. We obtained an MCI Library Link grant to create Electronic Entrepreneurs, which allows us to expand the use of electronic reference to neighborhood businesses. Electronic Entrepreneurs introduces small businesses to the powerful resources of the library and the Internet and trains them on laptop computers. In collaboration with the city's nine Merchant Coordinators and the Department of Economic Development, we are contributing to growth and development in the neighborhoods. Story #2 Business for Downtown, an organization that represents the needs of small businesses and influences decision-making about the future of the city's center, asked us to help them deal with attitude modification, to move people from "can't do" to "can do." We broadened the search to include organizational change and strategic management as processes involved in community management, improving community livability, and just plain neighborliness. Interestingly, a single book, Nadler's Ckolnpior7s of Cl7a11ge(1998), about mastering the skills of radical change, yielded the most striking material. Story #3 Recently, we talked with the city's Health Department about the Child Abuse Prevention Campaign launched by the Mayor, which brings together residents and organizations to raise awareness about child abuse and address the problem. The major part of the campaign, Safe Building for Children, involves declaring municipal and other secure buildings as "safe for children." Signs and posters are hung in main areas of the building with messages: "No hitting, screaming, pinching or dragging; Love, Respect, Protect your Child" and "Hartford Cares about Children; Love, Respect, Protect your Child." We at the library, wanting to be part of the Safe Building for Children designation at all sites including the Library-on-Wheels, began by talking about the training needed for library staff. It became apparent that the communications network created by the Neighborhood Teams and the library's relationship to so many grassroots organizations was a superb way to carry the campaign into the neighborhoods. In this way, the library could act as a catalyst to help neighborhoods foster the well-being of their children. Lessons The genius of the public library is meeting the individual wherever he or she is. Believe that, and it will take you to interesting places. And it will help you bring the power of the library into the community and into the everyday lives of people. It's been accepted wisdom that the Director needs to be in the community 40 to 60 percent of the time. But that is not enough. Most of the staff need to be in the community, face to face, learning in the most direct way possible. This is where the transformation takes place. It will no longer suffice for a few from management to be in the community, when the many are needed. C o n s e r v a t o ~Musicians Ihe Asylum Hill/Wesl En3 Open House When we are as close to our community as we can get - when we are present, listening, understanding - and responding to the real interests and needs of people we create a reservoir of goodwill, nlutual trust, and respect. It is a natural and positive consequence of getting library staff out of the library bos and into the everyday lives of people. It takes stepping out of our comfort zone and being in the place where we work. For more ir~formationcontact Louise Blalock at S60.533.SG52 or Iblalock@hartfordpl.lib.ct.us Listen. Learn. Link