Schlieffen's Perfect Plan

advertisement

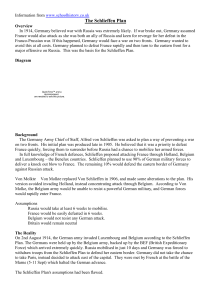

Schlieffen’s Perfect Plan T he heavily analyzed Schlieffen Plan was the perfect bad hand. The General Staff in Berlin faced known eneinvasion strategy, and the hardworking officers of mies on two fronts. To the west, the vengeful French marthe German General Staff knew it. The basic idea shaled their regiments, waiting for a chance to redress the traced all the way back to Hannibal. That’s not the humiliating failures of 1870–71 and retake their lost Hannibal known to Americans today as the vicious yet ur- provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. To the east, the dibane criminal mastermind of book and movie fame, but the sheveled but energetic millions of the Russian Empire original: Hannibal Barca of Carthage, one of the greatest bat- threatened to roll across the frontier. So the top graduates tlefield commanders in history. If you needed a good way to of the Berlin War Academy, the famous experts of the Gerwin—and win big—it only made sense to look to Hannibal. man General Staff, wrestled with the same dilemma that In his most decisive victory, Hannibal cornered a Roman plagued their country again and again: How do you win a army sent to stop him. The two forces met on August 2, two-front war? 216 B.C., facing off across a hot, flat Before Schlieffen’s time, Chancellor plain called Cannae, south of Rome. Otto von Bismarck and his General Tempting the overly aggressive RoStaff chief, the elder Field Marshal man commander to attack, Hannibal Helmuth von Moltke, didn’t resort to pulled back his center troops. Sensing Hannibal or hope. To deal with the Carthaginian weakness, exultant Rotwo-front problem, they just said man foot soldiers surged forward. As “no.” Both men accepted French enthey did, Hannibal swiftly swung in mity, but the war of 1870–71 indicated both of his flanking contingents, bagthat France alone could not beat Gerging the stunned Roman legionaries many. The key was to keep France isoin a double envelopment. More than lated, so Bismarck wove elaborate 60,000 trapped Romans died in the rediplomatic schemes to ensure good resultant slaughter. Historians rightly lations with Russia. For his part, von acclaimed Cannae as a brilliant battle Moltke drew up defensive plans to of encirclement and annihilation, with avoid provoking Germany’s powerful due credit to the vision and leadereastern neighbor. It made all the sense ship of the intrepid Hannibal. in the world. After 1888, however, the Of course, one win does not a final new German Kaiser, the headstrong By Lt. Gen. Daniel P. Bolger victory make. People still know about Wilhelm II, did not agree. He dumped U.S. Army retired Hannibal, but as for Carthage, not so Bismarck, retired von Moltke and much. The Romans learned from the Cannae debacle. watched calmly as Russia and France entered into formal Chastened, the legions reorganized, retrained, reequipped alliance. Wilhelm II didn’t fear a two-front war. Confident and struck back, grinding toward Carthage in campaign in Germany’s burgeoning strength, he intended to win it. after campaign. Eventually, after killing thousands of their Thus, Schlieffen and his General Staff mavens were told opponent’s best troops, Rome’s hard-bitten legionaries to design a perfect plan to win a two-front war. They took the fortified city of Carthage itself. They smashed the started with a big assumption on timing. In the west, the stout walls to dust, pulverized the neighborhoods block by French would mobilize in two weeks and attack into Alblock, put most of the men to the sword and sold the sur- sace-Lorraine. To the east, the Russians would take six viving population into slavery. weeks to gather their forces before attacking. German inMore than 2,000 years later, at the dawn of the 20th cen- telligence was reliable, and both adversaries were not all tury, the German General Staff—especially its dour chief, that careful about concealing their plans. General Staff offiField Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen—saw only the glitter- cers in Berlin crunched through population demographics, ing promise of a smashing, Hannibal-caliber envelopment. industrial production figures, map measurements and railSchlieffen venerated Cannae. His staff diagrammed it, dis- road statistics, but the numbers consistently told the tale. sected it and sought to replicate it. Having smashed the Beat the French in six weeks, and then race the German diDanes in 1864, the Austrians in 1866 and the French in visions across the country by rail to deal with the slower1870–71, Schlieffen’s officers figured that if anyone could arriving Russians. The trick was ensuring an early knockpull off a modern Cannae, it must be the guys in gray with out punch in France. As was their wont, the General Staff the spiked helmets. looked for relevant historical examples. Schlieffen and his The Germans needed a Cannae. Geography dealt them a men came upon Hannibal at Cannae. That would do. The Outpost 74 ARMY ■ August 2014 Bibliotheque Nationale de France French infantrymen take aim from behind protective earthworks during World War I. B y 1905, the perfect plan came together. To ensure rapid, decisive victory in the west, Schlieffen devised a modern Cannae on a continental scale. The General Staff amassed a crushing superiority against France, outnumbering the French almost two to one. Two of the German corps defended Alsace-Lorraine, beckoning the French to plunge forward to reclaim their lost provinces, as Schlieffen well knew they wanted to do. While the French attacked, the bulk of Schlieffen’s forces would sweep out in a great arc, marching through neutral Belgium, “letting the last man on the right brush the [English] Channel with his sleeve,” in the field marshal’s descriptive phrasing. This vast German array would descend on their foe’s rear echelon, cutting off French forces in Alsace-Lorraine, outflanking the panicked citizenry of Paris, and ending the war in the west in 42 days. The French were assessed as squabbling, excitable amateurs certain to advance merrily into the fatal trap. The few British divisions amounted to what the Kaiser dismissed as a “contemptible little army.” The Belgians were discounted altogether. The morality of bludgeoning through a neutral country did not figure in Schlieffen’s calculations. Clearly, Schlieffen took a lot of risk in the east. Only two Lt. Gen. Daniel P. Bolger, USA Ret., was the commander of Combined Security Transition Command-Afghanistan and NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan. Previously, he served as the deputy chief of staff, G-3/5/7, and as the commanding general, 1st Cavalry Division/commanding general, Multinational Division-Baghdad, Operation Iraqi Freedom. He holds a doctorate in Russian history from the University of Chicago and has published a number of books on military subjects. He recently was named a senior fellow of the AUSA Institute of Land Warfare. corps would hold the line as the Russians built up, but the Germans thought little of the Russians. Tsar Nicholas II appeared weak and easily confused, his armies humbled by the Japanese in a brutal 1904–05 war, his restive populace shot through with revolutionary sentiment and hobbled by widespread illiteracy. The supposed “Russian steamroller” leaked steam at every joint, and the roller looked pretty cracked and rusted. The tsar’s hapless hordes would be easy prey once France had fallen. The Germans rehearsed their perfect plan over and over. Mobilization drills linked up 2 million men, weapons, uniforms, supplies and horses at key German railway stations. Then, in an intricate, well-oiled ballet, more than 200,000 rail cars practiced forming into trains and heading west. When German mobilization ran flat out, one troop train crossed the Rhine River at Cologne every six minutes, monitored by General Staff men with perfectly synchronized stopwatches. Schlieffen’s successor, the younger Helmuth von Moltke, tinkered with the details. He moved two more corps to the east—you never knew with the Russians, since they might be early—and shifted six more corps into Alsace-Lorraine, just in case the French got lucky. But that still left 27 German corps to make the big envelopment. The basics remained intact: blow away France with a massive right wheel through neutral Belgium, then use the wonderful German railway network to speed the victorious veterans to the east to clobber the slow-assembling Russians. It was massive. It was beautifully crafted. It was perfect. On August 1, 1914, von Moltke got his chance. A fracas in the Balkans pitted Austria-Hungary against Russia. Ever excitable—and a bit fuzzy on the current war plan—Wilhelm wanted to support his Austrian ally without tangling with France or bringing in Britain by violating neutral BelAugust 2014 ■ ARMY 75 gium. Hearing the Kaiser’s intent, von Moltke nearly passed out. With all the tables of figures, all the battle drills, all the practice maneuvers, the millions moving, the hundreds of trains clicking west, von Moltke gasped, “Your Majesty, it cannot be done.” The great German General Staff, the finest military minds in Europe, the scions of the great Hannibal, had only one plan. They had to attack France. They had to go through Belgium. And so they did. tle of France occurred on the Marne River, but the wrong side won. Exhausted German troops faltered and fell back. The perfect plan didn’t allow for that. There was no Plan B. Four horrific years of trench warfare ensued. A century later, what can we learn from Schlieffen’s perfect plan? Rather than trying to conjure the ghost of Hannibal, Schlieffen and his proud General Staff cadres might have been better served to look to one of their own, Carl von Clausewitz. In his magisterial work On War, Clausewitz, who had fought in all too many battles, warned of what he termed friction: “Countless minor incidents—the kind you can never really foresee—combine to lower the general level of performance.” Clashing armies, bent on mortal combat, generate friction as surely as two sticks rubbed together. It’s as endemic to war as wetness is to water. No computer, no secret weapon and no trickery can banish friction. That was true in France in 1914. It’s true today. Beware the perfect plan: It will fail. And then what? In 1914, the result was World War I. A hundred years later, it’s a sobering reminder of the high price of military arrogance. We do well to keep it in mind as we fight today’s wars and prepare for those to come. ✭ Rive r River Ou rth e 20 30 Ri ver Worms Speyer Gemersheim Wissembourg C A Colmar A er LEGEND Freiburg 4 Mulhouse Phase Line For German Movement M+22 Fortified Areas 40 SCALE OF MILES A ve Ri r OVER HISTORY DEPARTMENT USMA B ne Sao C Vesoul Belfort Basel SWITZERLAND D Germany’s Schlieffen Plan was to invade through neutral Belgium and sweep southwest to outflank French troops. 76 ARMY ■ August 2014 3 Strasbourg L iv Langres Karlsruhe LEFT WING: Sixth and Seventh Armies U.S. Army/USMA Campaign Atlas to the Great War 10 xxxx FIRST DUBAIL Epinal R 0 Auxerre n River e Ri ver St. Die e Mosell N e r er Chatillon la xxxx SEVENTH HEERINGEN (127,00) e r ve Ri v R i ve r River Montargis 0 Ri v Mirecourt Bar sur Aube Donon ur th e r Rive Ri Charmes NORTHWEST EUROPE ELEVATIONS IN METERS 200 400 800 Rive r xxxx Sarrebourg SECOND CASTELNAU Luneville os el le RIGHT WING: First and Second Armies Belgian neutrality, Fifth Army was to move to the north and Fourth Army was to move left of the Third Army. Neufchateau Chaumont WESTERN FRONT, 1914 2 Kaiserlautern M Au be In event of German violation of M E Troyes e g Loin Sens G Bitche xxxx SIXTH Morhange Pont-a-Moussan RUPPRECHT (220,00) Chateau Salins Dieuze Saverne Commercy Nancy Toul St. Dizler River e n Oppenheim CENTER: Fourth and Fifth Armies S Bar le Duc rne Ma n Sei River r St. Avoid Meus r ve Siene Schlieffen Plan of 1905 and French Plan XVII Kreuznach Nahe River Trier xxxx Marieulles ve n Ri C Arcis sur Aube ve Ri Rhi ne Ourcq ST Ri River N ai Orn ain v Ri RE re Eu A Provins Metz THIRD Vandieres RUFFY LANGLE de CARY St. Mihiel (RESERVE) Revigny r ST. GOND MARSHES M M ve r xxxx Saarlouis FIFTH er CROWN PRINCE Sarrebrucken (200,00) Mars-La-Tour xxxx FOURTH Montmirail Mainz ar Sa FO e Verdun Morin r ve Mannheim Briey Etain Conflans St. Menehould xxxx Epernay Ri Frankfurt Merzig E Mont Blanc r Chateau Thierry Marne River Yo n 4 Ri Thionville NN Ri ve Y Lahn Longwy GO Vesle N Mayen Hillesheim FOURTH Luxemburg ALBRECHT Saarburg (180,000) Virton A NTA INS r Rive M lle Riv e Dyl e R Maas r r Ge tt e Craonne Aisne R Prum xxxx THIRD HAUSEN (180,000) Bitburg Diekirch Arlon E Giessen Coblenz LUXEMBURG Sedan xxxx FIFTH LANREZAC Rethel LEFT WING: Third and Stenay Fifth Armies Nogent Pithiviers N Wiltz Neufchâteau Bouillon Rheims Chartres Fantainebleau Bastogne AR in Se Melun DE R La Roche Laon Gd Mo rin Chateaudun AR FO S NE Hirson River Pt Etamps Dinat T ES MO U CHEMIN DES DAMES r ve Ri Chantilly R ver Ri v Rive r Barcy Meaux F G BULOW (260,000) Mezieres Juvigny Paris xxxxVerviers SECOND Marche Barisis Soissons 3 Huy RIGHT WING: First, Second and Third Armies ES Ai lett e s r Givet Le Fere Pontoise Deux Ri R Sc he ld e Dendre E V O D F O IT A R T S er Guise r Rive Roye Compiegne M Rive 1 r Rive Sieg HURTGEN FOREST Liege use Me er Florennes Siegen Sieburg r Euskirchen Echternach Beauvais e is O Warve Vervins Rouen y Da re mb Sa Ham Noyon Evreux Thuin Maubeuge Ri v Cologne Aachen Fumay Montdidier 37 Maastricht Tongres Gembloux Namur Charleroi Mons Peronne St. Quentin VillersChaulres Bretonneux Cantigny + Soignies ne 2 ne R xxxx FIRST KLUCK (320,000) r Ou Albert Proyart ve r n Se s ay Ri R Bapaume 3 1 Da ys Amiens Dury er 2D +2 Dieppe Louvain e iv Auinoye Queant Cambrai Le Cateau Avesnes Doullens e M ve r ve Ri er iv La Basse Loos Lens Drocourt Escout Riv Souchez Vimy Douai Arras So m m U Ri BRUSSELS Lille Neuve Chapelle Festubert M+ me r Hasselt RS Ypres Passchendaele Lys River Abbeville I De t Erf DE St. Omer Hazebrouck Montreuil G r ve Boulogne r EGent L Staden Roulers M 1 i ve AN Ri Yser B Dixmude FL r oe Dunkirk Calais D Dusseldorf Roermond 8 miles Rhi R C Antwerp Bruges Zeebrugge Torhout os e B Ostend Nieuport Dover VO SG A ENGLAND E T he perfect plan came unglued almost from the start. The German General Staff could control the railroads and the supply depots, but couldn’t direct the activities of their enemies. The Belgians resisted and did so fiercely, gumming up the timetable. Four tough British divisions, manned by sharpshooting regulars with bolt-action Lee-Enfield rifles, convinced battered German divisions that each opposing battalion fielded dozens of machine guns. The French pushed into Alsace-Lorraine right on schedule— and failed in a bloody riposte—but they also rapidly assembled tens of thousands of spirited reserves and disciplined colonial troops to block the great German right wing. At the six-week mark, just as Schlieffen predicted, the climactic bat-