Denial By Design… - ODSP Action Coalition

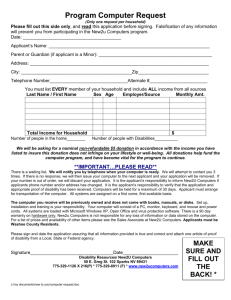

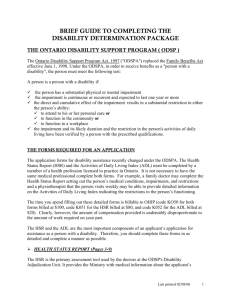

advertisement