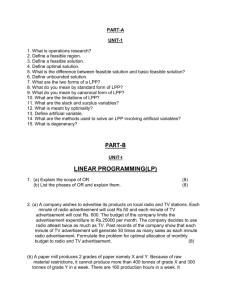

CHAPTER-2 LP

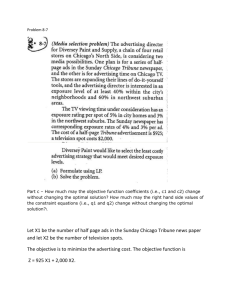

advertisement

INDUSTRIAL STATISTICS AND OPERATIONAL MANAGEMENT

2: Linear Programming Problem (LPP)

Dr. Ravi Mahendra Gor

Associate Dean

ICFAI Business School

ICFAI HOuse,

Nr. GNFC INFO Tower

S. G. Road

Bodakdev

Ahmedabad-380054

Ph.: 079-26858632 (O); 079-26464029 (R); 09825323243 (M)

E-mail: ravigor@hotmail.com

CONTENTS

Introduction

Requirements of a Linear Programming Problem

Model components

Basic Assumptions (Properties) of LP

Steps of formulating Linear Programming Problem (LPP)

Exercise

General form of LPP

Solving the Linear Programming Problem

Graphical Method of solving LPP

Extreme point approach

Iso-profit (cost) function line approach

Special cases in LP

Alternative (or Multiple) Optimal Solution

An Unbounded Solution

Infeasible Solution

Redundant Constraint

Simplex Method

Simplex Algorithm : (Maximization Case)

Simplex Algorithm : Minimization case

Two – Phase Method

Big – M method

Duality in LPP

Duality Theorems

Review Exercise

CHAPTER 2

LINEAR PROGRAMMING (LP)

2.1 Introduction

A typical mathematical program consists of a single objective function, representing either profits to be

maximized or costs to be minimized, and a set of constraints that circumscribe the decision variables. In the case of

a linear program (LP) the objective function and constraints are all linear functions of the decision variables. At first

glance these restrictions would seem to limit the scope of the LP model, but this is hardly the case. Because of its

simplicity, softwares are capable of solving problems containing millions of variables and tens of thousands of

constraints have been developed. Countless real-world applications have been successfully modeled and solved

using linear programming techniques.

Linear programming is a widely used model type that can solve decision problems with thousands of

variables. Generally, the feasible values of the decision variables are limited by a set of constraints that are described

by mathematical functions of the decision variables. The feasible decisions are compared using an objective function

that depends on the decision variables. For a linear program the objective function and constraints are required to be

linearly related to the variables of the problem.

The examples in the forthcoming section illustrate that linear programming can be used in a wide variety of

practical situations. We illustrate how a situation can be translated into a mathematical model, and how the model

can be solved to find the optimum solution.

A Linear Programming problem (LPP) is a special case of a Mathematical Programming problem. From

an analytical perspective, a mathematical program tries to identify an extreme (i.e., minimum or maximum) point of

a function f(x1, x2, …xn), which furthermore satisfies a set of constraints, e.g., g(x1, x2, …xn) ≥ b. Linear programming

is the specialization of mathematical programming to the case where both, function f - to be called the objective

function and the problem constraints are linear.

From an applications perspective, mathematical (and therefore, linear) programming is an optimization

tool, which allows the rationalization of many managerial and/or technological decisions required by contemporary

techno-socio-economic applications. An important factor for the applicability of the mathematical programming

11

methodology in various application contexts is the computational tractability of the resulting analytical models.

Under the advent of modern computing technology, this tractability requirement translates to the existence of

effective and efficient algorithmic procedures able to provide a systematic and fast solution to these models. For

Linear Programming problems, the Simplex algorithm, discussed later in the text, provides a powerful computational

tool, able to provide fast solutions to very large-scale applications, sometimes including hundreds of thousands of

variables (i.e., decision factors). In fact, the Simplex algorithm was one of the first Mathematical Programming

algorithms to be developed (George Dantzig, 1947), and its subsequent successful implementation in a series of

applications significantly contributed to the acceptance of the broader field of Operations Research as a scientific

approach to decision making.

As it happens, however, with every modeling effort, the effective application of Linear Programming

requires good understanding of the underlying modeling assumptions, and a pertinent interpretation of the obtained

analytical solutions. Therefore, in this section we discuss the details of the LP modeling and its underlying

assumptions.

2.2 Requirements of a Linear Programming Problem

In the past 50 years, LP has been applied extensively to defence, industrial, financial, marketing,

accounting, and agricultural problems. Even though these applications are diverse, all LP problems have four

properties in common.

1. All problems seek to maximize or minimize some function, usually profit or cost. We refer to this property as the

objective function of an LP problem. The major objective of a typical manufacturer is to maximize rupee profits.

In the case of a trucking or railroad distribution system, the objective might be to minimize shipping costs. In any

event, this objective must be stated clearly and defined mathematically.

2. The second property that LP problems have in common is the presence of restrictions, or constraints, that limit

the degree to which we can pursue our objective. For example, deciding how many units of each product in a

firm's product line to manufacture is restricted by available personnel and machinery. Selection of an advertising

policy or a financial portfolio is limited by the amount of money available to be spent or invested. We want,

therefore, to maximize or minimize a quantity (the objective function) subject to limited resources (the

constraints).

12

3. There must be alternative courses of action to choose from. For example, if a company produces three different

products., management may use LP to decide how to allocate among them its limited production resources (of

personnel, machinery, and so on). Should it devote all manufacturing capacity 10 make only the first product,

should it produce equal amounts of each product, or should it allocate the resources in some other ratio? If there

were no alternatives to select from, we would not need LP.

4. The objective and constraints in linear programming problems must be expressed in terms of linear equations or

inequalities. Linear mathematical relationships just mean that all terms used in the objective function and

constraints are of the first degree (that is, not squared, or to the third or higher power, or appearing more than

once).

You will sec the term inequality quite often when we discuss linear programming problems. By inequalities we

mean that not all LP constraints need be of the form A + B = C. This particular relationship, called an equation,

implies that the term A plus the term B are together exactly equal to the term C. In most LP problems, we see

inequalities of the form A + B ≤ C or A + B ≥ 2C.

2.2.1 Model Components :

Model consists of linear relationships representing a firm’s objectives and resource constraints.

•

Decision variables : mathematical symbols representing levels of activity of an operation.

•

Objective function : a linear mathematical relationship describing an objective of the firm, in terms of

decision variables, that is to be maximized or minimized

•

Constraints : restrictions placed on the firm by the operating environment stated in linear relationships of

the decision variables.

•

Parameters / cost coefficients : Numerical coefficients and constants used in the objective function and

constraint equations.

2.2.2 Basic Assumptions (Properties) of LP

Technically, there are five additiona1 requirements of an LP problem:

1. We assume that conditions of certainty exist; that is, numbers in the objective and constraints are known with

certainty and do not change during the period being studied.

2. We also assume that proportionality exists in the objective and constraints. This means that if production of 1 unit

of a product uses 3 hours of a particular scarce resource, then making 10 units of that product uses 30 hours of the

13

resource.

3. The third technical assumption deals with additivity, meaning that the total of all activities equals the sum of the

individual activities. For example, if an objective is to maximize profit = Rs.8 per unit of first product made plus

Rs.3 per unit of second product made, and if 1 unit of each product is actually produced, the profit contributions

of Rs.8 and Rs.3 must add up to produce a sum of Rs. 11.

4. We make the divisibility assumption that solutions need not be in whole numbers (integers). Instead, they are

divisible and may take any fractional value. If a fraction of Q product cannot be produced (for example, one-third

of a bottle), an integer programming problem exists.

5. Finally, we assume that all answers or variables are nonnegative. Negative values of physical quantities are

impossible; you simply cannot produce a negative number of chairs, shirts, lamps, or computers.

In the next section, let us see the steps of mathematical formulation of the problem.

2.3 Steps of formulating Linear Programming Problem (LPP) :

The following steps are involved to formulate LPP :

Step 1 : Identify the decision variables of the problem.

Step 2 : Construct the objective function as a linear combination of the decision variables.

Step 3 : Identify the constraints of the problem such as resources, limitations, inter-relation between variables etc.

Formulate these constraints as linear equations or inequations in terms of the non-negative decision variables.

Thus, LPP is a collection of the objective function, the set of constraints and the set of the non-negative constraints.

Let us study some examples illustrating the formulation of a linear programming problem.

Example 2.1 : The ABC Furniture Company produces tables and chairs. The production process for each is similar

in that both require a certain number of hours of carpentry work and a certain number of labor hours in the painting

and varnishing department. Each table takes 4 hours of carpentry and 2 hours in the painting and varnishing shop.

Each chair requires 3 hours in carpentry and 1 hour in painting and varnishing. During the current production period,

240 hours of carpentry time are available and 100 hours in painting and varnishing time are available. Each table

sold yields a profit of Rs.7; each chair produced is sold for a Rs.5 profit.

ABC Furniture's problem is to determine the best possible combination of tables and chairs to manufacture in

order to reach the maximum profit. The firm would like this production mix situation formulated as a linear

programming problem.

14

We begin by summarizing the information needed to formulate and solve this problem (see Table 1.1). Further,

let us introduce some simple notation for variables to be used in the objective function and constraints:

X1 = number of tables to be produced

X2 = number of chairs to be produced

Now we can create the LP objective function in terms of X1 and X2. The objective function is maximize profit =

Rs.7X1 + Rs.5X2.

Our next step is to develop mathematical relationships to describe the two constraints in this problem. One

general relationship is that the amount of a resource used is to be less than or equal to (≤) the amount of resource

available.

Table 1.1 ABC Furniture Company Data

Department

Carpentry

Painting and varnishing

Profit per unit

Hours required to

produce 1 unit

Tables Chairs

(x2)

(x1)

4

3

2

1

Rs. 7

Rs. 5

Available hours

Per week

240

100

In the case of the carpentry department, the total time used is(4 hours per table) (number of tables produced) + (3

hours per chair) (number of chairs produced)

So the first constraint may be stated as follows: Carpentry time used is ≤ carpentry time available.

4X1 + 3X2 ≤240 (hours of carpentry time)

Similarly, the second constraint is as follows: Painting and varnishing time used is ≤ painting and varnishing time

available.

2 X1 + 1X2 ≤ 100 (hours of painting and varnishing time)

Both of these constraints represent production capacity restrictions and affect the total profit. For

example, ABC Furniture cannot produce 70 tables during the production period because if X1 = 70, both constraints

will be violated. It also cannot make X1 = 50 tables and X1 = 10 chairs. Why? Because this would violate the second

constraint that no more than 100 hours of painting and varnishing time be allocated. Hence, we note one more

important aspect of linear programming; that is, certain interactions will exist between variables. The more units of

one product that a firm produces, the fewer it can make of other products. How this concept of interaction affects the

optimal solution will be seen when we tackle the graphical solution approach.

15

Thus for this problem the LP formulation is :

Find x1 and x2 so as to

Maximize ( the objective function ) Z = 7x1 + 5x2

Subject to (the constraints) 4x1 + 3x2 ≤240

2 x1 + 1x2 ≤ 100

and x1 , x2 ≥ 0

Example 2.2 (Production Allocation Problem) A manufacturer produces two types of models M and N. Each M

model requires 4 hours of grinding and 2 hours of polishing; whereas each N model requires 2 hours of grinding and

5 hours of polishing. The manufacturer has 2 grinders and 3 polishers. Each grinder works for 40 hours a week and

each polisher works for 60 hours a week. Profit on model M is Rs.3 and model N is Rs.4. Whatever is produced in a

week is sold in the market. How should the manufacturer allocate his production capacity to the two types of models

so that he may make the maximum profit in a week ?

Solution : Let x1 be the number of model M to be produced and

x2 be the number of model N to be produced.

Clearly x1 , x2 ≥ 0.

The manufacturer gets profit of Rs.3 for model M and Rs.4 for model N. So the objective function is to maximize

profit P = 3x1 + 4x2.

It is given that each model M requires 4 hours and each model N requires 2 hours for grinding. The maximum

available time for grinding is 40 hours and there are two grinders. So we have the constraint on the availability of

the hours of grinding,

4x1 + 2x2 ≤ 80

Again model M requires 2 hours of polishing and model N requires 5 hours of polishing. The maximum available

time for polishing is 60 hours and there are three polishers. Thus the constraint for the hours available for polishing

is,

2x1 + 5x2 ≤ 180

Thus, the manufacturer’s allocation problem is to

Maximize P = 3x1 + 4x2.

subject to the constraints :

4x1 + 2x2 ≤ 80 , 2x1 + 5x2 ≤ 180 , and x1 , x2 ≥ 0.

16

Example 2.3 (Inspection Problem) A company has two grades of inspector 1 and 2, who are to be assigned for a

quality control inspection. It is required that at least 2,000 pieces be inspected per 8 – hour day. Grade 1 inspector

can check pieces at the rate of 40 with an accuracy of 97 %. Grade 2 inspector checks at the rate of 30 pieces per

hour with an accuracy of 95 %. The wage rate of a Grade 1 inspector is Rs.5 per hour while that of a Grade 2

inspector is Rs.4 per hour. An error made by an inspector costs Rs.3 to the company. There are only nine Grade 1

inspectors and eleven Grade 2 inspectors available in the company. The company wishes to assign work to the

available inspectors so as to minimize the daily inspection cost.

Solution : Let x1 and x2 be the number of Grade 1 and Grade 2 inspectors doing inspections in a company

respectively. Clearly x1 , x2 ≥ 0.

One hour cost of inspection incurred by the company while employing an inspector = cost paid to the inspector +

cost of errors made during inspection. Thus, costs for

Inspector Grade 1 = 5 + 3 * 40 * (1 – 0.97) = Rs.8.60

Inspector Grade 2 = 4 + 3 * 30 * (1 – 0.95) = Rs.8.50

Both Grade inspector works for 8 hours a day. So the objective function (to minimize daily inspection cost) is

Minimize C = 8 (8.60 x1 + 8.50 x2) = 68.80 x1 + 68.00 x2.

Now the constraint of the inspection capacity of the inspectors for 8 – hours is

8 * 40x1 + 8 * 30x2 ≥ 2000

Also, company has only nine Grade 1 inspectors and eleven Grade 2 inspectors. So we have x1 ≤ 9 and x2 ≤ 11.

Thus, LPP is

Minimize C = 68.80 x1 + 68.00 x2.

subject to the constraints :

320x1 + 240x2 ≥ 2000

x1 ≤ 9

x2 ≤ 11.

and

x1 , x2 ≥ 0.

Example 2.4 : The Sky shop promotes its products from a large city to different parts in the state. The Sky shop has

budgeted up to Rs.8,000 per week for local advertising. The money is to be allocated among four promotional

media: TV spots, newspaper ads, and two types of radio advertisements. Sky shop’s goal is to reach the largest

17

possible high-potential audience through the various media. The following table presents the number of potential

customers reached by making use of an advertisement in each of the four media. It also provides the cost per

advertisement placed and the maximum number of ads that can be purchased per week.

medium

audience

cost per ad(rs.)

reached per

maximum ads

per week

ad

TV spot (1 minute)

5,000

800

12

Daily newspaper (full-page ad)

8,500

925

5

Radio spot (30 seconds, prime time)

2,400

290

25

Radio spot (1 minute, afternoon)

2,800

380

20

Sky shop’s contractual arrangements require that at least five radio spots be placed each week. To ensure a broadscoped promotional campaign, management also insists that no more than Rs.1,800 be spent on radio advertising

every week. Formulate this problem as a LPP.

Solution :

The problem can be stated mathematically as follows. Let

X1 = number of 1-minute TV spots taken each week.

X2 = number of full-page daily newspaper ads taken each week

X3 = number of 30-second prime-time radio spots taken each week

X4 = number of 1-minute afternoon radio spots taken each week

Objective: Maximize audience coverage = 5,000X1 + 8,500X2 + 2,400X3 + 2,800X4

subject to

X1 ≤ 12 (maximum TV spots/week)

X2 ≤ 5

(maximum newspaper ads/week)

X3 ≤ 25

(maximum 30-second radio spots/week)

X4 ≤ 20

(maximum 1-minute radio spots/week)

800X1 + 925X2 + 290X3 + 380X4 ≤ 8,000

(weekly advertising budget)

X3 + X4 ≥ 5(minimum radio spots contracted)

290X3 + 380X4 ≤ Rs.1,800 (maximum rupees spent on radio)

with X1, X2, X3 and X4 ≥ 0

18

Example 2.5: A pharmaceutical company produces two products : A and B. Production of both products requires

the same process, I and II. The production of B results also in a by-product C at no extra cost. The product A can be

sold at a profit of Rs.3 per unit and B at a profit of Rs.8 per unit. Some of this by-product can be sold at a unit profit

of Rs.2, the remainder has to be destroyed and the destruction cost is Rs.1 per unit. Forecasts show that only up to 5

units of C can be sold. The company gets 3 units of C for each unit of B produced. The manufacturing times are 3

hours per unit for A on process I and II, respectively, and 4 hours and 5 hours per unit for B on process I and II,

respectively. Because the product C results from producing B, no time is used in producing C. The available times

are 18 and 21 hours of process I and II, respectively. Formulate this problem as an LP model to determine the

quantity of A and B which should be produced, keeping C in mind, to make the highest total profit to the company.

Solution : Let x1 units of product A be produced and x2 units of product B be produced. Let x3 and x4 units of

product C to be produced and destroyed respectively.

It is given that the company gets profit of Rs.3 per unit of product A, Rs.8 per unit of product B, Rs.2 per unit of

product C and looses Rs.1 for destroying one unit of the product C. So objective function is

Maximize profit P = 3x1 + 8x2 + 2x3 – x4.

Manufacturing constraints for products A and B are

3x1 + 4x2 ≤ 18

3x1 + 5x2 ≤ 21

Manufacturing constraints for by-product C are

x3 ≤ 5

- 3x2 + x3 + x4 = 0

and

x1 , x2 , x3, x4 ≥ 0.

Example 2.6: A company, engaged in producing tinned food, has 300 trained employees on the rolls, each of whom

can produce one can of food in a week. Due to the developing taste of the public for this kind of food, the company

plans to add to the existing labor force by employing 150 people, in a phased manner, over the next five weeks. The

newcomers would have to undergo a two-week training programme before being put to the work. The training is to

be given by employees from among the existing ones and it is known that one employee can train three trainees.

Assume that there would be no production from the trainers and the trainees during training period as the training is

off-the-job. However, the trainees would be remunerated at the rate of Rs.300 per week, same rate as for the trainers.

19

The company has booked the following orders to supply during the next five weeks :

Week

:

1

2

3

4

5

No. of Cans

:

280

298

305

360

400

Assume that the production in any week would not be more than the number of cans ordered for so that

every delivery of the food would be ‘fresh’.

Formulate this problem as an LP model to develop a training schedule that minimizes the labour cost over

the five-week period.

Solution : Let x1, x2, x3, x4 and x5 be number of trainees appointed in the beginning of the week 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5,

respectively. The objective is to minimize the total labor force, i.e.

Minimize Z = 5x1 + 4x2 + 3x3 + 2x4 + x5.

subject to the

Capacity constraints :

300 – (x1 / 3) ≥ 280

; 300 – (x1 / 3) – (x2 / 3) ≥ 298

300 + x1 – (x2 / 3) – (x3 / 30) ≥ 305 ;

300 + x1 + x2 – (x3 / 3) – (x4 / 3) ≥ 360

300 + x1 + x2 + x3 – (x4 / 3) – (x5 / 3) ≥ 400

New recruitment constraint :

x1 + x2 + x3 + x4 + x5 = 150

and x1, x2, x3, x4, x5 ≥ 0.

Example 2.7 Pantaloons Industries, a nationally known manufacturer of menswear, produces four varieties of ties.

One is an expensive, all-silk tie, one is an all-polyester tie, and two are blends of polyester and cotton. The following

table illustrates the cost and availability (per monthly production planning period) of the three materials used in the

production process:

MATERIAL

COST PER

MATERIAL AVAILABLE PER

Silk

21

800

Polyester

6

3,000

Cotton

9

1,600

The firm has fixed contracts with several major department store chains to supply ties. The contracts require that

Pantaloons supply a minimum quantity of each tie but allow for a larger demand if Pantaloons chooses to meet that

20

demand. (Most of the ties are not shipped with the name Pantaloons on their label, incidentally, but with "private

stock" labels supplied by the stores.) Table 1.2 summarizes the contract demand for each of the four styles of ties,

the selling price per tie, and the fabric requirements of each variety.

TABLE 1.2 Data for Pantaloons

variety of tie

selling

price per tie

(Rs.)

monthly

contract

minimum

monthly

demand

material

required per tie

(yards)

material

requirements

All silk

All polyester

6.70

3.55

6,000

10,000

7,000

14,000

0.125

0.08

Poly-cotton

4.31

13,000

16,000

0.10

50% polyester-50%

Poly-cotton

4.81

6,000

8,500

0.10

30% polyester-70%

100% silk

100% polyester

Pantaloon’s goal is to maximize its monthly profit. Formulate the policy for product mix by a LP.

Solution : Let

X1 = number of all-silk ties produced per month

X2 = number of polyester ties

X3 = number of blend 1 poly-cotton ties

X4 = number of blend 2 poly-cotton ties

But first the firm must establish the profit per tie.

1. For all-silk ties (X1), each requires 0.125 yard of silk, at a cost of Rs.21 per yard. Therefore, the cost per tie is

Rs.2.62. The selling price per silk tie is Rs.6.70, leaving a net profit of (Rs.6.70 - Rs.2.62 = ) Rs.4.08 per unit of X1.

2. For all-polyester ties (X2), each requires 0.08 yard of polyester at a cost of Rs.6 per yard. The cost per tie is,

therefore, Rs.0.48. The net profit per unit of X2 is (Rs.3.55 -Rs.0.48 =)Rs.3.07.

3. For poly-cotton blend 1 (X3), each tie requires 0.05 yard of polyester at Rs.6 per yard and 0.05 yard of cotton at Rs.9

per yard, for a cost of Rs.0.30 + Rs.0.45 = Rs.0.75 per tie. The profit is Rs.3.56.

4. Try to compute the net profit for blend 2. You should calculate a cost of Rs.0.81 per tie and a net profit of Rs.4.

The objective function may now be stated as

Maximize profit = Rs.4.08X1 + Rs.3.07X2 + Rs.3.56X3 + Rs.4.00X4 subject to

0.125X1 ≤

0.08X2 + 0.05X3 + 0.03X4 ≤

800 (yards of silk)

3,000 (yards of polyester)

21

0.05X3 + 0.07X4 ≤

1,600 (yards of cotton)

X1 ≥

6,000 (contract minimum for all silk)

X1 ≤

7,000 (contract maximum)

X2 ≥ 10,000 (contract minimum for all polyester)

All Xi’s non negative

Example 2.8: The International City Trust (ICT) invests in short-term trade credits, corporate bonds, gold stocks,

and construction loans. To encourage a diversified portfolio, the board of directors has placed limits on the amount

that can be committed to any one type of investment. ICT has Rs.5 million available for immediate investment and

wishes to do two things: (1) maximize the interest earned on the investments made over the next six months, and (2)

satisfy the diversification requirements as set by the board of directors.

The specifics of the investment possibilities are as follows:

maximum investment

investment

interest earned (%)

Trade credit

7

(rs. millions)

1.0

Corporate bonds

11

2.5

Gold stocks

19

1.5

Construction loans

15

1.8

In addition, the board specifies that at least 55% of the funds invested must be in gold stocks and construction loans,

and that no less than 15% be invested in trade credit. Formulate as LPP.

Solution : To formulate ICT's investment decision as an LP problem, we let

X1 = rupees invested in trade credit

X2 = rupees invested in corporate bonds

X3 = rupees invested in gold stocks

X4 = rupees invested in construction loans

Objective:

Maximize rupees of interest earned = 0.07X1 + 0.11X2 + 0.19X3 + 0.15X4

subject to:

X1

≤ 1,000,000

X2

≤ 2,500,000

22

X3

≤ 1,500,000

X4

≤ 1,800,000

X3+ X4 ≥ 0.55 (X1 + X2 + X3 + X4)

X1

≥ 0.15 (X1 + X2 + X3 + X4)

X1 + X2 + X3 + X4 ≤ 5,000,000

And all Xi’s non negative

EXERCISE:

Q. An agriculturist has a farm with 126 acres. He produces Radish, Mutter and Potato. Whatever he raises is fully

sold in the market. He gets Rs.5 for radish per kg, Rs.4 for mutter per kg and Rs.5 for potato per kg. The average

yield is 1,500 kg of radish per acre, 1,800 kg of mutter per acre and 1,200 kg of potato per acre. To produce each

100 kg of radish and mutter and to produce each 80 kg of potato, a sum of RS.12.50 has to be used for manure.

Labour required for each acre to raise the crop is 6 man days for radish and potato each and 5 man days for mutter.

A total of 500 man days of labour at a rate of Rs.40 per man day are available. Formulate this problem as a LP

model to maximize agriculturist’s total profit.

Q. A Mutual Fund company has Rs.20 lakhs available for investment in government bonds, blue chip stocks,

speculative stocks and short-term bank deposits. The annual expected return and risk factor are given below :

Type of investment

Annual Expected Return (%)

Risk factor (0 to 100)

Government bonds

14

12

Blue chip stocks

19

24

Speculative stocks

23

48

Short-term bank deposits

12

6

Mutual fund is required to keep at least Rs.2 lakhs in short-term deposits and not exceed an average risk

factor of 42. Speculative stocks must be at most 20 % of the total amount invested. How should mutual fund invest

the funds so as to maximize its expected annual return ? Formulate this problem as LPP so as to optimize return on

the investment.

Q. Two alloys A and B are made from four different metals I, II, III and IV according to following specifications :

A : at most 80 % of I

B : between 40 % and 60 % of II

23

at most 30 % of II

at least 30 % of III

at most 50 % of III

at most 70 % of IV

The four metals are extracted from different ores whose constituents % of these metals, maximum available quantity

and cost per tonne are given below :

Ore

Maximum

Constitutions (%)

Other price Rs/Tonne

Quantity (tones) I

II III IV

1

1,000

20 10 30 30

10

30

2

2,000

10 20 30 30

10

40

3

3,000

5 5 70 20

0

50

Assuming the selling price of alloys A and B are Rs.200 and Rs. 300 per tonne respectively, formulate this problem

as a LP model selecting appropriate objective and constraints.

Q. Suppose a media specialist has to decide on the allocation of advertising in three media vehicles. Let xk be the

number of messages carried in the media, k = 1, 2, 3. The unit costs of message in the three media are Rs.1000, Rs.

750 and Rs. 500. The total budget available is Rs. 2,00,000 for the campaign period of one year. The first media is a

monthly magazine and it is desired to advertise not more than one insertion in one issue. At least six messages

should appear in second media. The number of messages in the third media should strictly lie between 4 and 8. The

expected effective audience for unit message in the media vehicles is shown below :

Vehicle Expected effective audience

1

80,000

2

60,000

3

45,000

Formulate this problem as an LP model to determine the optimum allocation that would maximize total effective

audience.

Q. A wine maker has a stock of three different wines with the following characteristics :

Wine

Proofs

Acid (%)

Specific gravity

Stock (Gallons)

A

27

0.32

1.70

20

B

33

0.20

1.08

34

C

32

0.30

1.1.04

22

A good dry table wine should between 30 and 31 degree proof, it should contain 0.25 % acid and should

have a specific gravity at least 1.06. The wine maker wishes to blend the three types of wine to produce as large a

24

quantity as possible of a satisfactory dry table wine. However, his stock of wine A must be completely used in the

blend because further storage would cause it to deteriorate. What quantities of wines B and C should be used in the

blend. Formulate this problem as an LP model.

Q. A paint manufacturing company manufactures paints at two plants. Firm orders have been received from three

large contractors. The firm has determined that the following shipping cost data is appropriate for these contractors

with respect to its two plants :

Contractor

Order size (gallon)

Shipping cost / Gallon (Rs.)

From Plant 1

From Plant 2

A

750

1.80

2.00

B

1,500

2.60

2.20

C

1,700

2.10

2.25

Each gallon of paint must be blended and tinted. The company’s costs with two operations at each of the two plants

are as follows :

Plant

Operation

Hours required/gallon

Cost/hour

Hours available

(Rs.)

1

2

Blending

0.10

3.80

300

Tinting

0.25

3.20

360

Blending

0.15

4.00

600

Tinting

0.20

3.10

720

Formulate this problem as an LP model.

25

2.4 General form of LPP :

The general LPP can be described as follows :

Given a set of m – linear inequalities or equalities in n – variables, we want to find non-negative values of

these variables which will satisfy the constraints and optimize (maximize or minimize) linear function of these

variables (objective function). Mathematically, we have m – linear inequalities or equalities in n – variables (m can

be greater than, less than or equal to n) of the form

ak1x1 + ak2x2 + … + aknxn {≥, =, ≤} bk, k = 1, 2, …, m

(2.1)

where for each constraint, one and only one of the signs ≥, =, ≤ holds, but the sign may vary from one constraint to

another. The aim is to find the values of the variables xj satisfying (2.1) and xj ≥ 0, j = 1, 2, …, n , which maximize

or minimize a linear function :

Z = c1x1 + c2x2 + … + cnxn.

(2.2)

The akj, bk and cj are assumed to be known constants. It is assumed that the variable xj can take any non-negative

values allowed by (2.1) and (2.2). These non-negative values can be any real number.

Thus, LPP is

Optimize Z = c1x1 + c2x2 + … + cnxn.

(2.3)

subject to the constraints

ak1x1 + ak2x2 + … + aknxn {≥, =, ≤} bk, k = 1, 2, …, m

and

xj ≥ 0, j = 1, 2, …, n

(2.4)

(2.5)

LPP in canonical form :

In general, ≤ constraints will be associated with maximization LPP and ≥ constraints with minimization

LPP. Let us write canonical form of maximization problem

Maximize Z = c1x1 + c2x2 + … + cnxn.

subject to the constraints

ak1x1 + ak2x2 + … + aknxn ≤ bk,

and

k = 1, 2, …, m

xj ≥ 0, j = 1, 2, …, n

The canonical form of minimization problem is

Minimize Z = c1x1 + c2x2 + … + cnxn.

26

subject to the constraints

ak1x1 + ak2x2 + … + aknxn ≥ bk, k = 1, 2, …, m

and

xj ≥ 0, j = 1, 2, …, n

Note : Different constraints may have different signs.

Note : When nothing is mentioned about the non-negativity of the variables, they are said to be unrestricted in sign.

To convert them in order that they can be set according to the format of LPP, we write the unrestricted variable xj as

a difference of two non-negative variables xj′ and xj″ i.e. xj = xj′ - xj″; xj′ ,xj″ ≥ 0.

Note : The theoretical discussion is based on n – decision variables and m – constraints (n ≥ m).

For solving any LPP by algebraic or analytic method it is necessary to convert inequalities (inequations)

into equality (equations). This can be done by introducing so called slack and surplus variables.

n

Consider an equality of the form ak1x1 + ak2x2 + … + aknxn ≤ bk. Introduce a variable sn+k = bk -

∑

akj

j =1

n

xj ≥ 0. So that

∑

akj xj + sn+k = bk. Such a variable sn+k is known as a slack variable. Similarly, consider an

j =1

equality of the form

n

ak1x1 + ak2x2 + … + aknxn ≥ bk. Introduce a variable sn+k = - bk +

∑

j =1

n

akj xj ≥ 0. So that

∑

akj xj - sn+k =

j =1

bk. Such a variable sn+k is known as a surplus variable. To each slack and / or surplus variable, assign a cost

coefficient of zero in the objective function i.e the slack and the surplus variables do not contribute to the objective

function.

Managerial Significance the Slack And The Surplus Variables:

Let us take the constraint 4X1 + 3X2 ≤ 240 (hours of carpentry time) from the Example 3.1 discussed earlier.

Here we think that the best combination of tables and chairs in the ABC furniture case may not necessarily use all

the time available in each department. We must therefore add to each inequality a variable which will take up the

slack, that is, the time not used in each department. This variable is called the slack variable. In this case if we write

the above inequality as equality as follows

4X1 + 3X2 + S1 = 240

27

then S1 represents the unused time in the carpentry department ( in general, unused amount of a resource)

Similarly, the constraint of the form 4X1 + 3X2 ≥240 if converted to equality, will look like

4X1 + 3X2 - S2 ≥ 240. Here the variable S2 represents the amount by which the carpentry hours will exceed 240 in

the solution. Hence they are the surplus amount of resources required.

Note :

After introducing slack / surplus variables, any given LPP can be expressed as under :

Maximize Z = c1x1 + c2x2 + … + cnxn.

subject to the constraints

ak1x1 + ak2x2 + … + aknxn + sn+k = bk,

and

k = 1, 2, …, m

xj ≥ 0, j = 1, 2, …, n+k

Using matrix notations, above LPP in canonical form as well as standard form can be expressed as follows :

Canonical Form : Maximize (Minimize) Z = cTx

Standard form : Maximize (Minimize) Z = cTx

subject to Ax ≤ (≥) b, x ≥ 0.

subject to Ax = b, x ≥ 0.

where c, x є Rn, b є Rm and A = (aij)m×n is a real valued matrix with rank equal to m ≤ n. Thus, A will have m linearly independent columns.

Significance of the slack and the surplus variables:

2.5 Solving the Linear Programming Problem:

Let us introduce some definitions for our standard LPP :

Solution : Any x є Rn which satisfies A x = b is a solution.

Feasible solution : Any x є Rn which satisfies A x = b, x ≥ 0 is called a feasible solution to the given LPP.

The set SF = { x є Rn : A x = b, x ≥ 0 } is known as the set of all feasible solutions.

Basic Solution : Any solution x in which at most m – variables are non-zero is called a basic solution.

Basic Feasible Solution : Any feasible solution x є Rn in which k (≤ m) variables have positive values and rest (n –

k) have zero values is called a basic feasible solution. If

k = m, the basic feasible solution is called non-

degenerate. If k < m, the basic feasible solution is called degenerate.

Our aim is to obtain a basic feasible solution to given LPP which optimizes the objective function.

Optimum Solution : Any feasible solution, x є Rn which optimizes the objective function Z = cTx is known as the

optimum solution to the given LPP.

28

Optimum Basic Feasible Solution : A basic feasible solution is said to be optimum if it optimizes the objective

function.

Unbounded Solution : If the value of the objective function can be increased or decreased infinitely without

violating the constraints then the solution is known as unbounded solution.

Let us discuss some of the fundamental results.

Consider LPP :

Maximize (Minimize) Z = cTx

subject to Ax = b, x ≥ 0.

Let SF = { x є Rn : A x = b, x ≥ 0 } denote the set of all feasible solutions.

Theorem 2.1 SF is a convex set.

Proof : Let x1, x2 є SF and λ є [0, 1] be any scalar. Then A x1 = b and A x2 = b, x1 ≥ 0,

x2 ≥ 0. Consider a convex

combination of x1 and x2 (say) xλ . Then xλ = λ x1 + (1 – λ) x2. Obviously, xλ ≥ 0.

Further A xλ = A(λ x1 + (1 – λ) x2) = λAx1 + (1 – λ) Ax2 = λ b + (1 – λ)b = b, implying

xλ є SF . Hence, SF is a convex set.

Note 1: If SF is a null set then there is no solution to given LPP.

Note 2: If SF is a closed bounded convex set, i.e. a convex polyhedron, given LPP will have an optimum solution

assigning finite value to the objective function.

Note 3: If SF is a convex set unbounded in some direction of Rn, then LPP will have a solution but the optimum

value of the objective function may be finite or infinite.

Theorem 2.2 Suppose the set SF of feasible solutions to the given LPP is non-empty then the basic feasible solution

to the LPP (if it exists) lies at the vertex of a convex polygon.

Proof : Suppose SF has p – vertices (say) x1, x2, …, xp. Let x0 be the basic feasible solution to given LPP. Two cases

may arise :

Case (i) : x0 is vertex of convex polygon. Then result is obvious.

Case (ii) : Let x0 be interior point of is vertex of SF . Then x0 can be expressed as convex combination of its

p

vertices. That is there exists scalars λ1, λ2, …, λp with

0 ≤ λ j≤ 1, 1 ≤ j ≤ p and

∑

j =1

29

λj = 1 such that

p

x0 =

∑

λj xj

(2.6)

j =1

Since x0 is optimum, we have

cTx0 ≥ cTxj for all 1 ≤ j ≤ p

(2.7)

In particular, let x0 be such that

cTxm ≥ cTxj for all 1 ≤ j ≤ p

(2.8)

From (2.7) and (2.8), cTx0 ≥ cTxm

(2.9)

Again, cTxm ≥ cTxj for all 1 ≤ j ≤ p then λj cTxm ≥ λj cTxj for all 1 ≤ j ≤ p.

p

λj cTxm ≥

∑

j =1

p

λj cTxj implies cTxm

∑

j =1

p

λj ≥ cT

∑

λj xj

j =1

i.e cTxm ≥ cTx0

(2.10)

From (2.9) and (2.10), it follows that cT x0 = cTxm .

Thus, there always exists a vertex xm є SF such that is cTxm optimum value. Thus, if a basic feasible

solution to a given LPP exists then one of the vertex will give optimum value to the objective function.

Theorem 2.3 The set of optimal solutions to the LPP is convex.

Proof : Let SF0 denotes the set of optimal solutions. If SF0 is empty or singleton then it is convex. Let SF0 contains

more than one solution (say) x10 , x20 є SF0 .Then cTx10 = cTx20 = max Z. Consider convex combination of x10 and x20

as w0 = λ x1 + (1 – λ) x2 , 0 ≤ λ ≤ 1. Then cTw0 = cT { λ x10 + (1 – λ) x20 } = λ cT x10 + (1 – λ) cT x20 = λ max Z + (1 –

λ)max Z = max Z. Thus, w0 є SF0. SF0 is convex.

Theorem 2.4 If the convex set of the feasible solution of Ax = b, x ≥ 0 is a convex polyhedron then at least one of

the extreme points give a basic feasible solution.

If the basic feasible solution occurs at more than one extreme point, the value of the objective function will

be same for all convex combinations of these extreme points.

Proof : Let x1, x2, …, xk be the extreme points of the feasible region F of the LPP defined in (2.3) – (2.5). Suppose

xm is the extreme point among x1, x2, …, xk at which the value of the objective function is maximum (say Z*). Then

Z* = cT xm

(2.11)

30

Now, consider a point x0 є SF , which is not an extreme point and let Z0 be the corresponding value of the objective

function. Then Z0 = cT x0

(2.12)

Since x0 is not an extreme point, it can be expressed as a convex combination of the extreme points x1, x2, …, xk of

the feasible region F where F is assumed to be a closed and bounded set. The there exists scalars λ1, λ2, …, λk with

k

∑

λ j = 1, 0 ≤ λ j ≤ 1,

1 ≤ j ≤ k such that x0 = λ1x1 + λ2 x2 + … + λk xk. Therefore (2.12) becomes

j =1

Z0 = cT { λ1x1 + λ2 x2 + … + λk xk } = λ1cT x1 + λ2 cT x2 + … + λk cT xk ≤ cT xm i.e. Z0 ≤ Z* (from (2.11))

which implies that an optimum solution, the extreme point solution is better than any feasible solution in F.

Second part of the Theorem :

Let x1, x2, …, xr (r ≤ k) be the extreme points of the feasible region F at which the objective function

assumes the same optimum value. This means Z* = cT x1 = cT x2 = … = cT xr .

r

Further let x = λ1x1 + λ2 x2 + … + λr xr ,

∑

λ j = 1, 0 ≤ λ j ≤ 1, 1 ≤ j ≤ r be the convex combination of x1, x2, …,

j =1

xr . Then

cTx = cT { λ1x1 + λ2 x2 + … + λr xr } = λ1cT x1 + λ2 cT x2 + … + λr cT xr

r

= λ1Z* + λ2 Z* + … + λr Z* = Z*

∑

λ j = Z*

j =1

which completes the proof.

Theorem 2.5 If there exists a feasible solution to the LPP then there exists a basic feasible solution to a given LPP.

Proof : Consider Maximize Z = c1x1 + c2x2 + … + cnxn.

subject to the constraints

a1x1 + a2x2 + … + anxn = b where ajT = (aj1, aj2, …, ajn) is j-th column of A.

Suppose that there exists a feasible solution to a above LPP in which k > m variables have positive values.

Without loss of generality, we assume that first k – variates have positive values. Then a1x1 + a2x2 + … + anxn = b .

31

For each aj є Rm, {a1, a2, …, ak) forms a dependent set. Assume that xr ≠ 0 and ar is linear combination of remaining

k

vectors of the set. So there exists scalars α1, α2, …, αr-1, αr+1, …, αk such that

∑

αjaj = 0 implies

j =1

k

∑

k

αjaj + αrar = 0 i.e. ar =

j =1

j≠ r

⎛ αj ⎞

⎜ − ⎟ aj

αr ⎠

j =1 ⎝

j≠ r

∑

k

We have arxr +

∑

k

ajxj = b i.e. arxr + xr

j =1

j≠ r

j =1

j≠ r

k

∑

(xj +

j =1

j≠ r

∑

⎛ αj ⎞

⎜ − ⎟ aj = b i.e.

⎝ αr ⎠

k

⎛ αj ⎞

⎛ αj ⎞

−

−

x

)

a

=

b.

Put

x

`=

x

+

x

.

Then

j

j

⎜

⎟ r

⎜

⎟ r j

∑ xj ` aj = b.

⎝ αr ⎠

⎝ αr ⎠

j =1

j≠ r

Thus, xj gives a new solution to given LPP which depends on (k – 1) – variables. In order that the new solution is

feasible, we require xj ` ≥ 0.

Clearly, xj +

xj

⎛ αj ⎞

⎛ αj ⎞

xr

≤

, αj ≠ 0.

⎜ − ⎟ xr ≥ 0, j = 1, 2, …, k. So xj ≥ ⎜ ⎟ xr . or

αr α j

⎝ αr ⎠

⎝ αr ⎠

Thus, if we choose ar such that

xj

xr

= min {

, αj ≠ 0 } then the solution will also be feasible. Thus, we get a

j

αr

αj

new feasible solution in which

(k – 1) – variables have positive values. This process can be continued till we get a

feasible solution in which m – variables have positive values.

Now let us discuss methods of solving LPP.

2.6 Graphical Method of solving LPP :

LPP involving two decision variables can be solved graphically. Using results proved in section 2.5, the

optimal solution to LPP can be found by evaluating the value of the objective function at each vertex of the feasible

region. The theorem 2.2 also states that an optimal solution to LPP will only occur at one of the extreme points. The

algorithm to solve LPP using graphical method is as follows :

32

2.6.1 Extreme point approach :

Step 1 : Formulate LPP as discussed in section 2.3.

Step 2 : Plot all constraints on the graph paper and shade the feasible region.

Step 3 : List all extreme points of the feasible region. Evaluate the values of the objective function at each extreme

point and the extreme point of the feasible region that optimizes (maximize or minimize) the objective function

value is the required basic feasible solution.

2.6.2 Iso-profit (cost) function line approach :

Follow step 1 and step 2 as stated in 3.6.1.

Step 3 : Draw an Iso-profit (iso-cost) line for small value of the objective function without violating any of the

constraints of the given LPP.

Step 4 : Move iso-profit (iso-cost)lines parallel in the direction of increasing (or decreasing) objective function.

Step 5 : The feasible extreme point for which the value of iso-profit (iso-cost) is maximum (minimum) is the optimal

solution. This means that while moving the iso-profit line in the required direction, the last point after which we

move out of the feasible region is the required optimal solution.

We discuss the steps involved in solving a simple linear programming model graphically with the help of the following

example.

Example 2.9: The PQR Company manufactures products X and Y. Each unit of X yields an incremental profit of

Rs.2, and each unit of Y, Rs.4. A unit of X requires four hours of processing at Machine Center A and two hours at

Machine Center B. A unit of Y requires six hours at Machine Center A, six hours at Machine Center B, and one hour at

Machine Centre C. Machine Center A has a maximum of 120 hours of available capacity per day. Machine Center B

has 72 hours, and Machine Center C has 10 hours. If the company wishes to maximize profit, how many units of X and

Y should be produced per day?

Solution: To maximize profit the objective function may be stated as

Maximize Z = 2X + 4Y

The maximization will be subject to the following constraints:

4X +6Y ≤ 120 (Machine Center A constraint)

2X + 6Y ≤ 72 (Machine Center B constraint)

1Y ≤ 10 (Machine Center C constraint)

33

X, Y ≥ 0

1. Formulate the problem in mathematical terms. The equations for the problem are given above.

2. Plot constraint equations.

The constraint equations are easily plotted by letting one variable equal zero and solving

for the axis intercept of the other. (The inequality portions of the restrictions are disregarded for this step.) For the

machine center A constraint equation when X = 0, Y = 20, and when Y = 0, X = 30. For the machine center B

constraint equation, when X = 0, Y = 12. and when Y = 0, X = 36. For the machine

center C constraint equation Y= 10 for all values of X. These lines are graphed.

3. Determine the area of feasibility. The direction of inequality signs in each constraint determines the area where a

feasible solution is found. In this case, all in equalities are of the less-than-or-equal-to variety, which means that it

would be impossible to produce any combination of products that would lie to the right of any constraint line on the

graph. The region of feasible solutions is unshaded on the graph and forms a convex polygon.

Plot the objective function. The objective function may be plotted by assuming some arbitrary total profit figure and

then solving for the axis coordinates, as was done for the constraint equations. Other terms for the objective function,

when used in this context, are the iso-profit or equal contribution line, because it shows all possible production combinations for any given profit figure.

4. Find the optimum point. It can be shown mathematically that the optimal combination of decision variables is always

found at an extreme point (corner point) of the convex polygon. In the graph there are four corner points (excluding the

origin), and we can determine which one is the optimum by either of two approaches. The first approach is to find the

values of the various corner solutions algebraically. This entails simultaneously solving the equations of various pairs

of intersecting lines and substituting the quantities of the resultant variables in the objective function. For example, the

calculations for the intersection of 2X + 6Y = 72 and Y = 10 are as follows:

Substituting Y= 10 in 2X+ 6Y=72 gives 2X + 6(10) = 72, 2X = 12, or X=6. Substituting X = 6 and Y = 10 in the

objective function, we get Profit = Rs.2X + Rs.4Y = Rs.2(6) + Rs.4( 10) = Rs.12 + Rs.40 = Rs.52

A variation of this approach is to read the X and Y quantities directly from the graph and substitute these

quantities into the objective function, as shown in the previous calculation. The drawback in this approach is that in

problems with a large number of constraint equations, there will be many possible points to evaluate, and the procedure

of testing each one mathematically is inefficient.

34

The second and generally preferred approach entails using the objective function or iso-profit line directly to

find the optimum point. The procedure involves simply drawing a straight line parallel to any arbitrarily selected initial

iso-profit line so that the iso-profit line is farthest from the origin of the graph. (In cost-minimization problems, the

objective would be to draw the line through the point closest to the origin.) In the figure, the dashed line labeled Rs.2X

+ Rs.4Y = Rs.64 intersects the most extreme point. Note that the initial arbitrarily selected iso-profit line is necessary to

display the slope of the objective function for the particular problem. This is important since a different objective

function (try profit = 3X + 3Y) might indicate that some other point is farthest from the origin. Given that Rs.2X +

Rs.4Y as Rs.64 is optimal, the amount of each variable to produce can be read from the graph: 24 units of product X

and four units of product Y. No other combination of the products yields a greater profit.

Y

(0,20)

2X + 4Y=64

(0,16)

(0,12)

Y=10

(0,8)

(24,4)

2X + 4Y=32

(36,0)

(30,0) (32,0)

(16,0)

X

Fig 2.1

Getting back to the problem, we now evaluate the value of the objective function at all the corner points of the

feasible region and select that point as the optimal solution which gives the maximum value. Here the corner points are

(0,0), (0,12), (6,10), (24,4) and (30,0). Out of these the maximum value of the objective function is at the point (24,4).

So the solution is : 24 units of product X and 4 units of product Y.

Example 2.10 Solve graphically the LPP :

Maximize z = 45x1 + 80x2

Subject to the constraints :

5x1 + 20x2 ≤ 400, 10x1 + 15x2 ≤ 450, and x1 , x2 ≥ 0.

35

Solution :

X2

(0,30)

(0,20)

(24,14)

(0,0)

(45,0)

(80,0)

X1

Fig. 2.2

The vertices of the shaded region are (0,0), (0, 20), (45, 0) and (24, 14). The values of the objective function z at

these extreme points are 0, 1600, 2025 and 2200 respectively. The maximum value of z = 2200 occurs at x1 = 24 and

x2 = 14.

Example 2.11 Solve graphically the LPP : Maximize z = 7x1 + 3x2 Subject to the constraints :

x1 + 2x2 ≥ 3 , x1 + x2 ≤ 4, 0 ≤ x1 ≤ 5/2, 0 ≤ x2 ≤ 3/2, and x1 , x2 ≥ 0.

Solution :

X2

X1=2.5

(0,4)

(0, 1.5)

(2.5, 1.5)

X2=1.5

(2.5, 0.25)

(3, 0)

Fig. 2.3

36

(4, 0)

X1

The vertices of convex polygon are (0, 1.5), (2.5, 0.25), (2.5, 1.5). The values of the objective function z are 4.5,

18.25, 22 respectively of which maximum is 22 obtained at (2.5, 1.5).

2.7 Special cases in LP :

2.7.1 Alternative (or Multiple) Optimal Solution : We try to under the concept of alternative or multiple solution

by considering the example.

Maximize P = 4x1 + 4x2

subject to the constraints :

x1 + 2x2 ≤ 10

6x1 + 6x2 ≤ 36

x1 ≤ 6 and x1 , x2 ≥ 0.

X2

(0,6)

(0,5)

(6,0)

(10,0)

X1

Fig. 2.4

It can be observed in Fig. 2.4 that the iso-profit line coincides with the edge of the convex feasible region. Thus

there will be infinitely many points at which the objective function is maximum. Hence, any point on the iso-profit

line will give optimum solutions and these solutions will yield the same maximum value of the objective function.

2.7.2 An Unbounded Solution :

We have discussed in section 2.5 that when the value of the decision variables in LP is allowed to increase

indefinitely without violating the feasible conditions, the solution is said to be unbounded. Here, the value of the

objective function may take value infinity.

37

Example 2.12 Solve (if possible) following LPP :

Maximize z = 3x1 + 4x2

subject to the constraints :

x1 - x2 = -1

- x1 + x2 ≤ 0

and

x1 , x2 ≥ 0.

X2

(0,1)

X1

(1,0)

(2,0)

Fig. 2.5

The feasible region suggests that the given LP has unbounded solution.

2.7.3 Infeasible Solution :

The infeasible solution occurs when no value of the variables satisfy all the constraints simultaneously;

equivalently, infeasible solution to the LP occurs when there is no unique feasible region.

Example 2.13 Verify that the following LP has infeasible solution.

Maximize z = 5x1 + 3x2 subject to the constraints : 4x1 + 2x2 ≤ 8, x1 ≥ 3, x2 ≥ 7 and x1 , x2 ≥ 0.

2.7.4 Redundant Constraint : A constraint which does not affect the feasibility of the region is said to be the

redundant constraint. Thus, the redundant constraint will not have any effect on the optimum value of the objective

function.

38

2.8 Simplex Method :

In general, any system may not be restricted to only two decision variables. In this section we try to explore

an algebraic technique to solve LPP iteratively in finite number of steps. This method is known as simplex method.

In this method, we start with one of the vertex or extreme point of SF and at each step or iteration move to an

adjacent vertex in such a way that the value of the value of the objective for iteration improves at each iteration. This

method either gives an optimum solution (if it exists) or gives an induction that the given LPP has an unbounded

solution.

Consider LPP :

Maximize (Minimize) Z = cTx

subject to Ax = b, x ≥ 0. Assume that the rank of (A, b) = rank of A equal

to m but less than or equal to n. This means that the set of constraint equation is consistent, all m – rows of A are

linearly independent and the number of constraints are less than or equal to the number of decision variables.

Further, Ax = b, can be written as

x1a1 + x2a2 + … + xnan = b

i.e. aj is the column of A associated with the variables xj , j = 1, 2, …, n. Since rank of A is equal to m less than n,

there are m – linearly independent columns of A. These m – linearly independent columns of A will form a basis in

Rm. Let B : m × m denote the matrix formed by m – linearly independent columns of A, then B = (b1, b2, …, bj, …,

bm)

will represent the basis matrix. Obviously, B : m × m will be non-singular so that B-1 exists. Any column (say) bi of

B is some column (say) aj of A. Note that it is not necessary that the arrangement of column in B should be in

accordance with those of A.

Any vector aj є A can be expressed as a linear combination of columns of B. i.e. for any aj є A, there exists

m

scalars y1j, y2j, …, ymj such that aj =

∑

yij bi or aj = Byj, j = 1, 2, …, n where yj = (y1j, y2j, …, ymj ). Thus,

j =1

A = (a1, a2, …, aj, …, an) = (By1, By2, …, Byj, …, Byn) = B(y1, y2, …, yj, …, yn)

i.e A = By implies y = B-1 A or yj = B-1 aj , j = 1, 2, …, n.

With this discussion, we are ready to study Simplex method.

Consider the LPP :

Maximize Z = cTx

subject to Ax = b, x ≥ 0.

39

The aim is to obtain an optimum basic feasible solution for given LPP. Since simplex method is an iterative method,

we assumed that an initial basic feasible solution is available.

Let B : m × m denote a basis matrix (say) B = (b1, b2, …, bj, …, bm). Each bi is some aj of A, i =1, 2, …, m

and j = 1, 2, …, n. The columns of A included in B are called basic vectors and those which are not in B are called

non-basic vectors. The variables vector x chosen corresponding to vectors in basis matrix B are known as basic

variables and rest are known as non-basic variables. Then the constraint equations Ax = b can now be written as BxB

+ PxR = b where B : m × m is the basis matrix and R : m × (n – m) is the non-basis matrix formed by the non-basic

vectors of A. xB : m × 1 is the vector corresponding to basic variables and xR : (n – m) × 1 is the vector

corresponding to non - basic variables. Taking xR = 0, we get BxB = b or xB = B-1b.

The basis matrix B : m × m is chosen in such a way that xB = B-1b ≥ 0. Then we have basic feasible solution to the

given LPP.

Let CB : m × 1 denote the cost vector corresponding to the variables in xB . Then the value of the objective

function for this solution is

ZB = cTB xB + cTR xR = cTB xB = cTB B-1b.

Further, corresponding to above basis matrix we define a new quantity

m

Zj = cTB yj =

∑

cTBi yij = cTB B-1b

i =1

Further, corresponding to above basis matrix we define a new quantity

m

T

cj = c

B

yj =

∑

cTBi yij cTB B-1aj , j = 1, 2, …, n.

i =1

The quantity zj – cj (or cj – zj), j = 1, 2, …, n is known as net evaluations. After obtaining a basic feasible solution

check following :

1) Whether the basic feasible solution is optimum or not ? and

2) If not to obtain a new improved basic feasible solution. This can be done by remaining one of the basic

vectors from the matrix B = (b1, b2, …, br, …, bm) and inserting a non-basic vectors of A = (a1, a2, …, aj,

…, an) in its place.

40

The problem is “Which basic variable should be removed from B and which of the non-basic variable should be

introduced in its place ?”

aj є A in its place. Let B*

Suppose we remove a basic vector br from B and introduce a non-basic vector

denote the non-basic matrix obtained by replacing aj in place of br then

B* = (b1, b2, …, br-1, aj , br+1, …, bm)

= (b1, b2, …, br-1, br + aj - br, br+1, …, bm)

= (b1, b2, …, br-1, br, br+1, …, bm) + (0, 0, …, 0, aj - br, 0, …, 0)

Therefore, B* = B + (aj - br) eTr where eTr є Rm is the r – th unit vector in Rm . This gives

B*-1 = B-1 -

B−1 (a j − b r )eTr B−1

1 + eTr B−1 (a j − b r )

= B-1 -

B−1 (a j − b r )eTr B−1

y rj

= B-1 -

(y j − e r )eTr B−1

y rj

In order that B*-1 can be obtained the necessary condition is yrj ≠ 0. Thus, aj can replace br if and only if yrj ≠ 0. The

new solution is then

*

-1

-1

xB = B b = (B -

= xB -

(y j − e r )eTr B−1

y rj

(y j − e r )eTr

y rj

Therefore, xB* = xB -

)b=B b-

(y j − e r )eTr B−1

y rj

b = xB -

(y j − e r )eTr

y rj

xB

xBr

x Br

(yj – er).

y rj

Hence, the new solution is xBi* = xBi -

xBi -

-1

x Br

(yj – 0), i = 1, 2, …, m, i ≠ r because in er, i-th element is zero. So xBi* =

y rj

x Br

x

x

yij or xBr* = xBr - Br (yrj -1) = Br .

y rj

y rj

y rj

We thus have a new basic solution. In order that the new solution is feasible, we require xBi* ≥ 0, i = 1, 2,

…, m i.e. xBr* =

Further, xBi -

x Br

x

> 0, i = 1, 2, …, m, i ≠ r. Since xBr ≥ 0, xBr* = Br > 0 if yrj > 0. Thus, we require that yrj > 0.

y rj

y rj

x Br

x Br x Bi

x

x

yij ≥ 0 implies

≤

, i = 1, 2, …, m. Hence, Br = min { Bi , yij > 0}.

i

y rj

y rj

yij

y rj

yij

41

(2.13)

Thus, the vector br to be removed from B should be chosen in accordance with (2.13). Let cB* denote the

new cost vector corresponding to the new solution then

cB* = (cB1, cB2, …, cBr-1, cBj, cBr+1, …, cBm)T

= (cB1, cB2, …, cBr-1, cBr + cj - cBr, cBr+1, …, cBm)T

and new value of the objective function is

Z* = cTB* xB*= [cTB + (cj – cBr)eTr ] [xB -

x Br

x

(yj – er)]. Put Br = θ

y rj

y rj

= cTB* xB*= [cTB + (cj – cBr)eTr ] [xB - θ (yj – er)]

= Z - θ (zj – cj )

(2.14)

Our aim is to maximize Z, and so we require Z* > Z equivalently zj – cj (or cj – zj) > 0 (< 0).

Therefore, the vector aj є A to be introduced into the basis matrix B must be such that zj – cj > 0 (or cj – zj

< 0). Note that determination of aj does not require information about br. However, determination of vector br to be

removed from the basis requires information about both r and j.

We should first determine the vector aj to be introduced into new basis and then using (2.13) determine the

vector br to be removed from B. Continuing in this may for finite number of steps, we can ultimately obtain

optimum solution. The new y - matrix is

*

*-1

y =B

-1

A = [B -

(y j − e r )eTr B−1

y rj

-1

] A = B A-

=y-

1

(yj – er) erTy

y rj

=y-

1

(yj – er) (yr1, yr2, …, yij, …, yrn)

y rj

Comparing the elements on both sides, we get yik* = yik -

So yij* = yij -

yrj* = yrj -

(y j − e r )eTr B−1

y rj

1

yij yrk

y rj

1

(yij yrj – 0), i =1, 2, …, m, i ≠ r , j = 1, 2, …, n, k ≠ j and

y rj

1

(yrj yrj – yrj) = 1.

y rj

42

A

Note :

1. While discussing simplex method, we have assumed an initial basic feasible solution, we have assumed an initial

basic feasible solution with a basis matrix B. If B = I then

B-1 = I then initial solution xB = B-1b = b and y matrix

is y = B-1A = A. Net evaluations, zj – cj = - cj + cBTB-1aj = - cj + cBTaj , j = 1, 2, …, n and value of the objective

function

Z = cBTxB = cBTb. Thus, we observe that if initial basis matrix is a unit matrix then it is easy to obtain

initial solution and related parameters. Hence, in order to obtain initial basic feasible solution, we shall assume that a

unit matrix is present as a sub-matrix of the coefficient matrix A.

2. For choosing incoming vector aj in the next basis, choose that zj – cj ( cj – zj)which is most negative (positive). If

two or more zj – cj ( cj – zj) have the same most negative (positive) value, choose any one of the corresponding

vector to enter into the basis.

3. After choosing the incoming vector, choose the outgoing vector which satisfies (2.13). If this minimum value is

assumed for more than two vectors, choose any one of the corresponding basis vector from B.

Following two theorems will state without proof.

Theorem 3.6 Every basic feasible solution to a LPP corresponds to a vertex of the set of feasible solution.

Theorem 3.7 For the LPP : Maximize Z = cTx

subject to Ax = b, x ≥ 0. A necessary and sufficient condition for a

basic feasible solution xB = B-1b corresponding to a basis matrix B : m × m to be optimum is that zj – cj ≥ 0 (or cj –

zj ≤ 0) for all j = 1, 2, …, n.

2.8.1 Simplex Algorithm : (Maximization Case)

To find an optimum basic feasible solution to a standard LPP (maximization case, all constraints ≤ , all bj

i.e all R.H.S values positive), perform following steps :

Step 1 : Select an initial basic feasible solution to initiate the solution.

Step 2 : Test for the optimality as discussed in section 3.6. That is if all zj – cj ≥ 0( cj – zj ≤ 0), then the basic feasible

solution is optimal. If at least for one of the coefficient matrix zj – cj < 0 (or cj – zj > 0) and elements in that columns

are negative (positive), then there exists an unbounded solution to the given problem. If at least one zj – cj < 0 ( cj –

zj > 0) and each of these has at least one positive (negative) element for some row then solution can be improved.

Step 3 : For selecting the variable entering into the basis, select a variable that has the most negative zj – cj value (or

most positive cj – zj). The column to be entered is called key column.

43

Step 4 : After selecting key column, next step is to decide the outgoing variable using (3.6) This ratio is called

replacement ratio (RR). The replacement ratio restricts the number of units of incoming variables that can be

obtained from the exchange. The row selected in this manner is called key row. The element at the intersection of

key row and key column is called key element.

Note that the division by negative or zero element in key column is not allowed. Denote these cases by -.

Step 5 : Now we want to find new solution. If the key element is 1, then don’t change the row in the next simplex

table. If the key element is other than 1, then divide element in that key row by that element including the element in

xB – column and formulate the new row. The new values of the elements in the remaining rows for the next iteration

can be evaluated by performing elementary operations on all rows so that all elements except the key element in the

key column are zero. This can be also calculated as follows

(New row numbers) = (numbers in old row)-[ (numbers above or below the key element)×(corresponding number in

the new row, that is the row replaced in the previous step)]

If new solution so obtained satisfies step 2 then terminate the process otherwise perform step 4 and step 5.

Repeat the steps for finite number of steps to obtain basic feasible solution i.e. no further improvement is

possible.

Example 2.14 Use simplex method to maximize z = 5x1 + 4x2

subject to the constraints : 4x1 + 5x2 ≤ 10, 3x1 + 2x2 ≤ 9, 8x1 + 3x2 ≤ 12 and x1 , x2 ≥ 0.

Solution : Writing given LPP in standard form, we need to add slack variables s1, s2 and s3 in the constraints. Thus

LPP is

Maximize z = 5x1 + 4x2 + 0s1+ 0s2 + 0s3

subject to the constraints :

4x1 + 5x2 + s1 = 10

3x1 + 2x2 + s2 = 9

8x1 + 3x2 + s3 = 12

and

x1 , x2 , s1, s2, s3 ≥ 0.

Putting x1 = x2 = 0, we get first iteration as

44

cj

5

4

0

0

0

RR

cB

B

xB

x1

x2

s1

s2

s3

0

s1

10

4

5

1

0

0

10/4

0

s2

9

3

2

0

1

0

9/3

0

s3

12

8

3

0

0

1

12/8 →

z

0

zj - cj

-5

-4

0

0

0

↑

Clearly, most negative zj – cj corresponds to x1. So x1 will enter into the basis. The minimum replacement ratio

corresponds to s3 so s3 will leave the basis. So key column corresponds to x1 and key row corresponds to s3. The

leading (key) element is 8 which is other than 1 so divide all elements of key row by 8 and using elementary row

transformations so that in key column entries of the first and second row are zero. The new iteration table is

cj

5

4

0

0

0

RR

cB

B

xB

x1

x2

s1

s2

s3

0

s1

4

0

7/2

1

0

-1/2

8/7 →

0

s2

9/2

0

7/8

0

1

-3/8

36/7

5

x1

3/2

1

3/18

0

0

1/8

9

z

15/2

zj - cj

0

-17/8

0

0

5/8

↑

Clearly, most negative zj – cj corresponds to x2 so x2 will enter into the basis. The minimum replacement ratio

corresponds to s1 so s1 will leave the basis. So key column corresponds to x2 and key row corresponds to s1. The

leading (key) element is 7/2 which is other than 1 so divide all elements of key row by 2/7 and using elementary row

transformations so that in key column entries of the second and third row are zero. The new iteration table is

45

cj

5

4

0

0

0

cB

B

xB

x1

x2

s1

s2

s3

4

x2

8/7

0

1

1

0

-1/7

0

s2

7/2

0

0

0

1

-2/8

5

x1

15/14

1

0

0

0

5/28

z

139/14

zj - cj

0

0

17/28

0

9/28

Since all zj – cj ≥ 0, the solution x1 = 15/14, x2 = 8/7 maximizes the z = 139/14.

Example 2.15 Maximize Z = 2x1 + 4x2,

subject to 2x1 + 3x2 ≤ 48,

x1 + 3x2 ≤ 42,

x1 + x2 ≤ 21,

and x1, x2 ≥ 0

We will check the optimality here by evaluating NER as Cj-Zj. Also we will format the table in a different way so

that the reader is accustomed to both the ways. We will make a continuous table in which all the iterations are taken

care of.

Introducing the slack variables and entering the values in the simplex table we get,

46

Cj →

2

4

0

0

0

↓

x1

x2

s1

s2

s3

R.H.S

R.R

Var→

Basis

↓

0

s1

2

3

1

0

0

48

48/3=16

0

s2

1

3

0

1

0

42

14 →

0

s3

1

1

0

0

1

21

21

N.E.R

2

4

0

0

0

Z=0

↑

=Cj-Zj

0

s1

1

0

1

-1

0

6

6→

4

x2

1/3

1

0

1/3

0

14

42

0

s3

2/3

0

0

-1/3

1

7

21/2

N.E.R

2/3

0

0

-4/3

0

Z = 56

=Cj-Zj

↑

2

x1

1

0

1

-1

0

6

4

x2

0

1

-1/3

2/3

0

12

0

s3

0

0

-2/3

1/3

1

3

N.E.R

0

0

-2/3

-2/3

0

Z = 60

=Cj-Zj

As all NER (Cj-Zj) entries are ≤ 0, the optimality criteria is satisfied and the solution obtained is optimal.

Thus, the final solution is x1 = 6, x2 = 12 and Maximum Z = 60

Example 2.16 Minimize Z = x1 - 3x2 + 2x3

subject to 3x1 - x2 + 3x3 ≤ 7, -2x1 + 4x2 ≤ 12, -4x1 + 3x2 + 8x3 ≤ 10 and x1, x2 , x3 ≥ 0

This being a minimization problem with all constraints of ≤ type, we will first convert it into a maximization

problem by multiplying the objective function Z with -1 and then maximizing the same.

i.e Maximize Z* = - Z = - x1 + 3x2 - 2x3

preparing the simplex table and solving,

47

Cj →

-1

3

-2

0

0

0

↓

x1

x2

x3

s1

s2

s3

RHS

R.R

Var→

Basis

↓

0

s1

3

-1

3

1

0

0

7

-7

0

s2

-2

4

0

0

1

0

12

3→

0

s3

-4

3

8

0

0

1

10

10/3

N.E.R

-1

3↑

-2

0

0

0

Z*=0

=Cj-Zj

0

s1

5/2

0

3

1

1/4

0

10

4→

3

x2

-1/2

1

0

0

1/4

0

3

-6

0

s3

-5/2

0

8

0

-3/4

1

1

-2/5

1/2 ↑

0

-2

0

-3/4

0

Z*=9

N.E.R

=Cj-Zj

-1

x1

1

0

6/5

2/5

1/10

0

4

3

x2

0

1

3/5

1/5

3/10

0

5

0

s3

0

0

11

1

-1/2

1

11

0

0

-13/5

-1/5

-8/10

0

Z*=11

N.E.R

=Cj-Zj

As all NER (Cj-Zj) entries are ≤ 0, the optimality criteria is satisfied and the solution obtained is optimal.

The optimum value of the original objective function will be obtained by taking –Z*.

Thus, the final solution is x1 = 4, x2 = 5, x3 = 0 and Minimum Z = - Z* = -11.

Example 2.17 :Use simplex method to maximize z = 2x1 + 3x2

subject to the constraints : - x1 + 2x2 ≤ 4, x1 + x2 ≤ 6, x1 + 3x2 ≤ 9 and x1 , x2 unrestricted.

48

Solution : s1, s2, s3 are slack variables introduced in given three constraints. Since x1 and x2 are unrestricted, we

introduce the non-negative variables x1′ ≥ 0, x1′′ ≥ 0 and x2′ ≥ 0, x22′′ ≥ 0 so that x1 = x1′ - x1′′ and x2 = x2′ - x2′′ .

cj

2

-2

3

-3

0

0

0

RR

cB

B

xB

x1′

x1′′

x2′

x2′′

s1

s2

s3

0

s1

4

-1

1

2

-2

1

0

0

2→

0

s2

6

1

-1

1

-1

0

1

0

6

0

s3

9

1

-1

3

-3

0

0

1

3

z

0

zj - cj