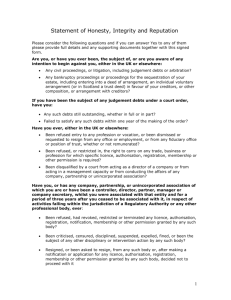

an evaluation of the Debt and Mental Health Evidence Form

advertisement